from Tellers of Weird Tales!

Pages

▼

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Nathaniel T. Babcock (1851-1928)

Nathaniel P. Babcock

Journalist, Editor, Author

Born December 28, 1851, New York, New York

Died February 13, 1928, Zanesville, Ohio

Journalist, Editor, Author

Born December 28, 1851, New York, New York

Died February 13, 1928, Zanesville, Ohio

I'll have to begin again with a question of names. In his first issue of a revived Weird Tales, Sam Moskowitz credited one of his authors as "Nathaniel T. Babcock." That credit seems to have come from Munsey's in 1892 and perhaps also from The Argosy in 1896. We now know that the author's real name was Nathaniel P. Babcock. In any case, one of the reasons for doing research is to correct mistakes made by previous researchers. I have received frequent corrections from readers of this blog. Although I haven't made all those corrections yet, I hope to get to them and I hope that you'll continue to send them in.

Nathaniel P. Babcock, by my best guess, was born on December 28, 1851, in New York City. (1) He may have been related to an old and prominent New England family named Babcock, but I have been unable to confirm that. H.P. Lovecraft must have known the Babcock name, for he used it in "A Shadow Over Innsmouth" (1936). Lovecraft's own family may have been related to the Babcock family as well through the Whipple line.

Babcock was a newspaperman. His obituary in the New York Times (Feb. 16, 1928, p. 3) states that he had worked in the newspaper business for fifty-three years, first with the New York Tribune, then with the World, the American, and with the Hearst syndicates. His story "The Man with the Brown Beard" was published in Munsey's in January 1892 and in The Argosy in February 1896. That was the story Moskowitz used in Weird Tales. Babcock also contributed to The Century, The Junior Munsey, Ladies' Home Journal, The Saturday Evening Post, and St. Nicholas Magazine between 1886 and 1903.

Babcock married a woman from Somerset, Ohio. At least one of his children was born in Zanesville. That would explain his connection to the Buckeye State. In February 1928, Babcock returned from Europe with his wife and daughter. Eleven days later, he died in a hospital in Zanesville. He was seventy-six years old.

Forty-five years after that, Sam Moskowitz placed "The Man with the Brown Beard" in his new Weird Tales and in his paperback anthology, Horrors in Hiding. Evidently it had proved elusive: despite the fact that "The Man with the Brown Beard" was the first--chronologically--of the stories listed in the first comprehensive index of fantasy in the Munsey periodicals (2), it had never before been reprinted. Moskowitz corrected the oversight, calling Babcock's story a "powerful tale of horror."

Nathaniel P. Babcock's Story in Weird Tales

"The Man with the Brown Beard" (Summer 1973, originally in The Argosy, Feb. 1896)

Update (Oct. 27, 2020): Reader Ricardo Gouvea asked about other short stories written by Nathaniel P. Babcock. I found a list of his credits on the website The FictionMags Index. I have found a few more credits in other places, so here is an updated list:

- "The Stranger Cat" (poem) in St. Nicholas, Jan. 1886

- "The Queerness of Quelf" (poem) in St. Nicholas, Apr. 1887

- "Silly Miss Unicorn" (poem) in St. Nicholas, July 1887

- "Love’s Dilemma" (poem) in The Century Magazine, Apr. 1888

- "Ruth’s Birthday" (poem) in St. Nicholas, Nov. 1888

- "His Majesty the King" (poem) in St. Nicholas, May 1889

- "The Man with the Brown Beard" (short story) in Munsey’s Magazine, Jan. 1892

- "When Moody and Sankey Stirred the Nation" (article) in Ladies’ Home Journal, Oct. 1897

- "Newspaper Head Lines" (article) in The Junior Munsey, Dec. 1901

- "Without Publicity" (short story) in The Black Cat, June 1902

- "The Cheseboro Heir" (short story) in The Buffalo Times, Oct. 19, 1902

- "My Red Cravat" (short story) in The Saturday Evening Post, July 11, 1903

- "The Day in June; or When Teddy Comes Home" (poem) in The Daily Arkansas Gazette, Mar. 31, 1910

- "The Dawn of Effort" (poem) in The Daily Arkansas Gazette, Apr. 26, 1910

- "Casabianca in 1910" (poem) in The San Francisco Examiner, June 28, 1910

- "The Fall of a Poet" (poem) in The Daily Arkansas Gazette, Nov. 19, 1910

Babcock was married to Caroline Maginnis Babcock (1856-1942) a native of Somerset, Ohio, and a member of the Froebel Society, an educational organization in Brooklyn, New York.

Notes

(1) I have seen birthdates of February 1852 and December 1853 as well. If the 1860 census is accurate, then the 1853 birthdate cannot be. Two sources indicate a birthdate in December--two (for December) against one (for February) leaves December 28, 1851, as the most likely date in my mind.

(2) The index, "Fantasy in the Munsey Periodicals" by William H. Evans, was serialized in Fantasy Commentator, a fanzine, in 1946-1947.

Text copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Albert Page Mitchell (1852-1927)

Edward Page Mitchell

Journalist, Editor, Short Story Writer

Born March 24, 1852, Bath, Maine

Died January 22, 1927, New London, Connecticut

The first thing to do here is to deal with the problem of names. "Albert Page Mitchell" is the name that appeared on the cover of two issues of the Sam Moskowitz Weird Tales of 1973-1974. That same name serves as a byline on the table of contents and in the interior of the magazine. These two issues of Weird Tales came out at about the same time as a book called The Crystal Man: Stories by Edward Page Mitchell, collected and with a biographical perspective by Moskowitz. That biographical perspective, entitled "Lost Giant of American Science Fiction," is a sixty-three page survey of American science fiction of the nineteenth century with a discussion of Mitchell's place therein. Overall, it's an admirable piece of work, but unless I'm missing something, not once is Mitchell referred to as "Albert Page Mitchell." There is mention of Mitchell's cousin, Albert G. Page, but otherwise, the Christian name "Albert" doesn't appear in relationship to the author, and he is referred to in every case either as "Mitchell" or "Edward Page Mitchell." (Moskowitz even calls him once "Edgar Page Mitchell.") So what's going on here? I can think of two possibilities: One, in rediscovering Mitchell, Moskowitz knew he had a scoop and he didn't want anybody to know about it before his book came out. Two, Moskowitz made a colossal mistake, conflating the names "Albert G. Page" and "Edward Page Mitchell" in the magazine Weird Tales. I can't see that Moskowitz would have gained anything by using a false name to protect his privy information. To me Moskowitz's use of the name "Albert" just looks like a blunder. If you do an Internet search on "Albert Page Mitchell," you'll find nothing but references to those two issues of Weird Tales (and an entry in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database). As far as I can tell, no one before or since has called Mitchell by the name "Albert Page Mitchell."

So Edward Page Mitchell it is.

Mitchell's biography is on Wikipedia. You can read it by clicking on this link. That biography seems to have been based on Moskowitz's own work in The Crystal Man. If Moskowitz is correct, then Mitchell--whom he called "'The Missing Link' in the history of American science fiction"--wrote the earliest known stories or very early stories on the topics of:

- Faster-than-light travel ("The Tachypomp," 1874)

- Teleportation ("The Man Without a Body," 1877)

- Mind transfer ("Exchanging Their Souls," 1877)

- Cybernetics ("The Ablest Man in the World," 1879)

- Cryogenic preservation ("The Senator's Daughter," 1879)

- Surgical alteration of personality ("The Professor's Experiment," 1880)

- An invisible man ("The Crystal Man," 1881)

- A time machine ("The Clock That Went Backward," 1881)

- A friendly alien life form ("The Balloon Tree," 1883)

- A mutated human with superior powers ("Old Squids and Little Speller," 1885)

Mitchell was a journalist; all of his known fiction was first published by his employer, the New York Sun, between 1874 and 1886. (1) Mitchell's first story, entitled "The Tachypomp," appeared in the Sun in January 1874 and again in Scribner's Monthly in April 1874. Concerned with faster-than-light travel in a decidedly non-Einsteinian way, "The Tachypomp" is also notable for its mention of an android and a tunnel through the earth. I'm not sure if Mitchell coined the term tachypomp, but its construction is simple enough: tachy, from the Greek, meaning "swift" or "rapid," and pomp, from the Latin, meaning "procession," also from the Greek, "to send." According to Wikipedia, physicist Gerald Feinberg coined the term tachyon for a hypothetical faster-than-light particle in 1967. Feinberg could not have known that an obscure nineteenth-century American writer had anticipated his construction.

Edward Page Mitchell spanned American science fiction from Edward Everett Hale (1822-1909), whom he knew as a young man, to Garrett P. Serviss (1851-1929) and Edward Bellamy (1850-1898), whom he met later in life. Mitchell also knew Frank Stockton (1834-1902), Madame Blavatsky (1831-1891), and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (1828-1914). Although he was interested in fantasy, science fiction, the supernatural, and the occult, Mitchell remained a solid citizen and a family man. He was on the editorial staff of the Sun in 1897 when Virginia O'Hanlon wrote her now famous letter asking if there is a Santa Claus. (2) My reason for bringing this up is not just to make a connection between Mitchell and a famous event. In 1991, Ed Asner played Edward P. Mitchell in a TV movie version of Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus. That would make Mitchell one of only a few Weird Tales authors to have been played in a movie or television show. (3)

Edward Page Mitchell died on January 22, 1927, in New London, Connecticut, at the age of seventy-four. It would take nearly half a century and the work of Sam Moskowitz--despite his mistakes--for him to be recognized as a major figure in American science fiction of the nineteenth century.

Notes

(1) Mitchell, an 1871 graduate of Bowdoin College, didn't begin working for the Sun until October 1875. He worked for newspapers in Maine and in Boston before that. Mitchell remained with the Sun the rest of his career, reaching the post of editor-in-chief in 1903 and retiring in 1922. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain taught at Bowdoin in two stints. His teaching was interrupted by service during the Civil War. He resigned in 1883.

(2) The reply--"Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus"--was written by another editor, Francis Pharcellus Church.

(3) Two others: Robert E. Howard played by Vincent D'Onofrio in The Whole, Wide World (1996), a fine and sympathetic biopic of the creator of Conan the Cimmerian; and H.P. Lovecraft, played by Jeffrey Combs and others in various films.

Edward Page Mitchell's Stories in Weird Tales

"The Balloon Tree" (Winter 1973, originally in the New York Sun, Feb. 25, 1883)

"The Devilish Rat" (Summer 1974, originally in the New York Sun, Jan. 27, 1978)

|

| The Crystal Man, Doubleday Science Fiction from 1973, compiled and with a historical and biographical essay by Sam Moskowitz. The artist is unknown. |

|

| I presume this is the same book in a Spanish edition. |

|

| Mitchell's work was also translated into Italian. His story, "An Uncommon Sort of Spectre," appeared in this book for youngsters. |

Revised slightly and corrected on January 22, 2017; revised slightly on August 9, 2021.

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Monday, October 29, 2012

Emma Frances Dawson (ca. 1839-1926)

Musician, Music Teacher, Poet, Translator, Short Story Writer

Born ca. 1839, Bangor, Maine

Died Feb. 6, 1926, Palo Alto, California

In writing about Emma Frances Dawson, I'm forced to go over ground already covered by other researchers and to write about things that have already been published. You'll find little about Emma on the Internet, and part of what you'll find is wrong. I think the straight scoop on her life and works is in a recently published annotated facsimile edition of her book An Itinerant House, and Other Stories. But because no one has written about her at length on the Internet, I'll write what I have found and hope that more will be forthcoming from my readers.

Emma Frances Dawson was born in 1838 or 1839 in Bangor, Maine, to John S. Dawson, a railroad contractor, and Salome "Lola" Emerson, supposedly a distant relative of Ralph Waldo Emerson. A birth year of 1851 for Emma F. Dawson is commonly cited on the Internet, but the 1850 census confirms a birth year of either 1838 or 1839. She was an only child. By September 1861 her parents were divorced. Both remarried. Salome chose John B. Cummings, occupation unknown and ten years her junior, as her husband. In 1870 and 1880, John S. Dawson, Emma's father, was enumerated in the census with his wife, Abby. (I believe she was the former Abigail Elizabeth Averill.) By that date--1880--Salome (then calling herself Lola Emerson) and her daughter Emma had relocated to the West Coast, about as far from their birthplaces as they could go while remaining in the United States.

More than one source asserts that Lola Emerson suffered from ill health. Sam Moskowitz called her "hopelessly invalid." Emma Dawson supported herself and her mother by writing and teaching music. She also wrote short stories and poems and translated works from Latin, Greek, French, German, Spanish, and Catalan. (Moskowitz included Persian in that list.) The Californian published her early story "The Dramatic In My Destiny" in its January 1880 issue. Over the years, she penned several more stories of the weird or supernatural variety. These were collected in a book called An Itinerant House, and Other Stories in 1896. Today that book is hard to find and priced in the hundreds of dollars. That could be one of the reasons why Thomas Loring and Company of Portland, Maine, published a hardbound facsimile edition, adding three stories plus other material to the original, in 2007. The book is called An Itinerant House and Other Ghost Stories. It's edited by John Pinkney and Robert Eldridge and includes an introduction by Robert Eldridge. It also includes ten original illustrations by a fellow San Franciscan, Ernest C. Peixotto (1869-1940).

Emma Frances Dawson is supposed to have been a protégé of Ambrose Bierce, despite the fact that they were roughly the same age. (She was slightly older.) Whatever their relationship, Bierce wrote of her: "She is head and shoulders above any writer on this coast with whose work I am acquainted." After her death, Helen Throop Purdy observed: "She possessed an imagination and a style that were rare, her tales often rivalling [sic] Poe's in eeriness." In 1883, she won first place in a national contest for her poem, "Old Glory." In addition to The Californian, she contributed to The Argonaut, The News Letter, The Overland Monthly, Short Stories, and The Wasp.

Emma Dawson lived in the San Francisco area most of her life, initially on Russian Hill in the city, and after the earthquake and fire of 1906, in Palo Alto. She was something of a recluse and may have lived in poverty. One source suggests that she starved to death. Helen Throop Purdy reported that Emma had a stroke of paralysis and laid on the floor of her house, undiscovered, for two or three days afterwards. She was taken to the hospital and died a week later, on February 6, 1926. Emma F. Dawson would have been about eighty-six years old. Despite her obscurity and despite having written only a few fantasy stories, she is highly regarded among fantasy fans of today.

Emma Dawson lived in the San Francisco area most of her life, initially on Russian Hill in the city, and after the earthquake and fire of 1906, in Palo Alto. She was something of a recluse and may have lived in poverty. One source suggests that she starved to death. Helen Throop Purdy reported that Emma had a stroke of paralysis and laid on the floor of her house, undiscovered, for two or three days afterwards. She was taken to the hospital and died a week later, on February 6, 1926. Emma F. Dawson would have been about eighty-six years old. Despite her obscurity and despite having written only a few fantasy stories, she is highly regarded among fantasy fans of today.

Emma Frances Dawson's Story in Weird Tales

"The Dramatic In My Destiny" (Winter 1973, originally in The Californian, Jan. 1880)

Further Reading

I have seen two references to biographical material on Emma Dawson. First is the reprinting of her book, An Itinerant House and Other Ghosts Stores (2007). The other is The Dictionary of North American Authors Deceased Before 1950. The Itinerant House, and Other Stories, in a copy from the collection of Stanford University, is available on Google Books.

Update (Mar. 13, 2014): You can find an obituary, "Emma Frances Dawson," by Helen Throop Purdy, in California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Mar., 1926), p. 87.

Update (Mar. 13, 2014): You can find an obituary, "Emma Frances Dawson," by Helen Throop Purdy, in California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Mar., 1926), p. 87.

Update (Apr. 2, 2023); Following is an article on Emma Francis Dawson from the San Francisco Examiner, January 31, 1926, page 3:

Thanks to Dr. Elizabeth McCarthy of the School of English, Trinity College, Dublin, for further information. Thanks also to Richard Bleiler for sending obituaries of Emma Dawson.

Updated on March 13, 2014; April 2, 2023.

Text copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Updated on March 13, 2014; April 2, 2023.

Text copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Jack L. Thurston (1919-2017)

Artist, Illustrator, Sculptor, Movie Poster Artist

Born August 5, 1919, St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada

Died April 27, 2017, New York State

The last issue of Sam Moskowitz's four-issue revival of Weird Tales bears an unsigned cover illustration from an uncredited artist. Jaffery and Cook, in their index of Weird Tales, list the cover artist as "unknown." Earlier today, I posted the image with the same credit: "unknown." Now the mystery is solved and the artist is known. We can thank John at Monster Magazine World for that. Thanks, John!

As John points out in his comment, the cover illustration for Weird Tales, Volume 47, Number 4 (Summer 1974), is a reworked and flipped version of the cover of Satan's Disciples by Robert Goldston from 1962. As an artist, I can see that there's something wrong in the reproduction of the Weird Tales cover. Now I know why. Here's the cover:

Now here's the original:

As you can see, the whole image has been darkened and recolored, and the background and the other figures have been removed. In addition, the rocks have been replaced with a table, a cup, a skull, and a couple of standing braziers, suggesting a scene of human sacrifice or a black mass. I wonder if another artist or even the engraver reworked the original image somehow. The illustration seems too poor in quality to have been a reworked version of the original art, suggesting that Mr. Thurston was not responsible. It looks to me like a swipe. In any case, the artist's signature is clearly legible in the lower right corner of the cover of Satan's Disciples. It reads "Thurston" and thereby reveals the rest of the mystery.

Jack LeRoy Thurston was born on August 5, 1919, in St. Catherines, Ontario. He's a hard man to track in public records. Although there is record of his crossing over into the United States as early as 1923, I haven't found Mr. Thurston in the 1920, 1930, or 1940 census. The earliest mention of him I have found is in an article on men in the service from The Niagara Falls Gazette, December 26, 1944, page nine. That article mentions his mother (Mrs. Harry L. Thurston of that city), his wife (Mrs. Barbara Fisher Thurston, also of Niagara Falls), his rank in the U.S. Navy (petty officer, third class), and the places where he was stationed (Naval Training Center, Sampson, New York; and Naval Training Station, Norfolk, Virginia). The article also includes a photograph of the artist. Jack Thurston enlisted in the Navy in 1943 and earned his citizenship in January 1946.

In the article, Mr. Thurston was described as a former employee in the art department of Gilman Fanfold Corporation. From what I can gather, Gilman Fanfold manufactured office supplies or forms and had a facility in Niagara Falls. According to AskArt, Mr. Thurston "served during World War II as a sculptor to scale of enemy terrain." His schooling came at the Buffalo Art Institute, Jepson's Fine Arts School, and the Art Center of Design in Hollywood. He was the author and illustrator of The Adventures of Skoot Skeeter from 1948. I don't know when he began illustrating book covers and movie posters, but I suspect it was in the 1950s and no later than the early 1960s. Unfortunately, Mr. Thurston is not included in Walt Reed's otherwise very fine editions of The Illustrator in America or in Vincent Di Fate's Infinite Worlds.

I don't know whether Mr. Thurston is still living. If so, he would be ninety-three years old. I would like to think he's still out there somewhere, drawing and painting, for he created some truly beautiful works of art.

Update: Two commenters below, one anonymous, the other named Christy Kalan, have alerted us that Jack L. Thurston, a longtime resident of New Rochelle, New York, died on April 27, 2017, at age ninety-seven. Ms. Kalan urges readers to pass on to Mr. Thurston's colleagues word of his death. On behalf of the world of science fiction, fantasy, and other genre fiction and art, I would like to offer to the Thurston family our condolences.

Update: Two commenters below, one anonymous, the other named Christy Kalan, have alerted us that Jack L. Thurston, a longtime resident of New Rochelle, New York, died on April 27, 2017, at age ninety-seven. Ms. Kalan urges readers to pass on to Mr. Thurston's colleagues word of his death. On behalf of the world of science fiction, fantasy, and other genre fiction and art, I would like to offer to the Thurston family our condolences.

Above: A gallery of book covers by Jack L. Thurston. An accomplished draftsman, a fine colorist, and a painterly artist who was good with the human figure, Mr. Thurston was comfortable in every genre. By the way, the last two authors--Edison Marshall and Day Keene--were also tellers of weird tales.

Second Update (Dec. 7, 2018): I have found a few newspaper articles on Jack Thurston and more of his illustrations. First, Thurston lived and worked in Rochester, New York, for many years. He was, in addition to being an illustrator, a writer, advertising artist, and teacher of drawing and oil painting at East Evening High School in Rochester. He was also a member of the Rochester Art Association and exhibited his work in the Rochester area. He illustrated his own children's book, The Adventures of Skoot Skeeter (1948), as well as two books by Karl H. Bratton, Tales of the Magic Mirror (1949) and Tales of Once Upon a Time (1960). (See the comment below.) Thurston's work for these books is charming, maybe a little old fashioned. Then, sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s, Thurston began creating paperback book covers and movie posters and his style changed, becoming dramatic, forceful, energetic. A good example of this style is shown in his poster for One Million Years B.C., from 1966, that high point of pop culture in America. Finally, I have found that Jack Thurston did two back covers for Mad, from October 1971 and March 1972.

|

| The Adventures of Skoot Skeeter by Jack Thurston (1948). |

|

| Tales of the Magic Mirror by Karl H. Bratton, illustrated by Jack Thurston (1949). |

|

| Movie poster for One Million Years B.C. (1966) by Jack L. Thurston. |

|

| Back cover design for Mad #146, October 1971, by Jack L. Thurston. |

|

| Back cover design for Mad #149, March 1972, by Jack L. Thurston. |

Updated in 2017 and on December 7, 2018. Updated again on April 2, 2023.

Thanks to all who have commented and provided more information on Jack L. Thurston. Thanks also to Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site for images and information.

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Thanks to all who have commented and provided more information on Jack L. Thurston. Thanks also to Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site for images and information.

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Authors from Sam Moskowitz's Weird Tales

As a business, Weird Tales was seldom on firm footing. It nearly died a-borning in 1923-1924. Throughout the following decades, the magazine struggled and was sold in 1938 to Short Stories, Inc. Dorothy McIlwraith came on as editor in 1940 and kept Weird Tales alive for a more than a decade, but in September 1954, "The Unique Magazine" finally gave up the ghost. In a later anthology, editor Marvin Kaye called Weird Tales "the magazine that never dies," and true to form, it has returned again and again. Leo Margulies, who purchased the Weird Tales property in the 1950s, issued several paperback anthologies in the 1960s. Then in the early '70s, editor Sam Moskowitz assembled four new issues of the magazine. Roughly the size of an old pulp magazine (or comic book), perfect bound, and amounting to 96 pages per issue, Moskowitz's Weird Tales included reprints from the original run, new stories from various authors, and some very old stories unearthed by the editor and given new life. I have written about American authors of the nineteenth century whose work was reprinted in the Weird Tales of the Farnsworth Wright era (1924-1940). Less well known are the authors from Sam Moskowitz's Weird Tales.

One of the labels I use in this blog is "Weird Tales from the Past." I have used this label for authors who died before Weird Tales began publishing in March 1923. (1) Farnsworth Wright availed himself of weird tales from the past. Dorothy McIlwraith was disinclined to do so. But when Sam Moskowitz brought back Weird Tales, he raided old story magazines for content, thereby creating a whole new category of authors for indexers and researchers like me.

It appears as though Moskowitz spent a good deal of the 1960s and '70s digging through old magazines for weird and fantastic fiction. He assembled the stories he found in a number of books and relied heavily on them for his four issues of the revived Weird Tales. Following is a list of authors whose stories in Weird Tales appeared in the Sam Moskowitz issues. These are authors who may have lived into the first Weird Tales era, but by 1973-1974, they were gone. For most of them, their only appearance in Weird Tales was during the very brief Moskowitz era. I have already written about some of them. (Click on the links to find them.) I'll get to work on the others over the next few weeks. Think of this as a companion to my previous posting, "Nineteenth Century American Authors."

- Emma Francis Dawson (ca. 1839-1926)

- Ian McClaren (1850-1907)

- Albert Page Mitchell (1852-1927)

- Nathaniel T. Babcock (1853-1928)

- F. Marion Crawford (1854-1909)

- W.C. Morrow (1854-1923)

- George Griffith (1857-1906)

- Albert Bigelow Paine (1861-1937)

- Cleveland Moffett (1863-1926)

- Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933)

- Wardon Allan Curtis (1867-1940)

- Gustav Meyrink (1868-1932)

- Frank Norris (1870-1902)

- Hildegarde Hawthorne (1871-1952)

- Perley Poore Sheehan (1875-1943)

- Muriel Campbell Dyar (1875-1963)

- William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918)

- Edison Marshall (1894-1967)

Notes

(1) There are exceptions: Robert W. Chambers, Gustav Meyrink, Giovanni Magherini Graziani, Fedor Sologub, Jean Richepin, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Gaston Leroux. Most of these authors were European and may not have known their work was being reprinted in Weird Tales.

|

| The second issue, from the fall of 1973, with cover art by Gary van der Steur after Hannes Bok's cover from March 1940. |

|

| Issue number 3, Winter 1973, cover art by Bill Edwards. The recent movies Willard (1971) and Ben (1972) would have been on people's minds when this issue appeared. |

|

| The last issue of Sam Moskowitz's revival of Weird Tales, from the summer of 1974. The cover artist is unknown. |

|

| As a bonus, here's Virgil Finlay's interior illustration for "The Medici Boots" by Pearl Norton Swet. |

|

| And here's the cover that took the place of Finlay's original. The artist was Margaret Brundage. |

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Frank Norris (1870-1902)

Artist, Journalist, War Correspondent, Editor, Short Story Writer, Novelist

Born March 5, 1870, Chicago, Illinois

Died October 25, 1902, San Francisco, California

Born March 5, 1870, Chicago, Illinois

Died October 25, 1902, San Francisco, California

Frank Norris is the last of the nineteenth century American authors from my list of many months ago, and I see that just a couple of days ago, October 25, 2012, was the 110th anniversary of his death. I guess I'm tardy on two counts, but I'll go on. Benjamin Franklin Norris, Jr. was born on March 5, 1870, in Chicago, Illinois, and moved with his family to San Francisco in 1884. Norris studied art at the Académie Julian in Paris and afterwards attended the University of California at Berkeley and Harvard University. By that time he had already begun his career as a writer. The last few years of his very short life were busy: correspondent, South Africa (1895-1896); editorial assistant, San Francisco (1896-1897); war correspondent, Cuba (1898); on the staff of Doubleday and Page, New York (1899).

Norris died of a ruptured appendix on October 25, 1902, in San Francisco. In an all-too-brief writing life, he wrote some very big books. I can list his credits here without taking up too much space:

Norris died of a ruptured appendix on October 25, 1902, in San Francisco. In an all-too-brief writing life, he wrote some very big books. I can list his credits here without taking up too much space:

- Moran of the "Lady Letty": A Story of Adventure Off the California Coast (1898)

- Blix (1899)

- McTeague: A Story of San Francisco (1899)

- A Man's Woman (1900)

- A Deal in Wheat and Other Stories of the New and Old West

- The Octopus: A Story of California (1901)

- The Pit: A Story of Chicago (1902)

- Vandover and the Brute (1914)

Norris is placed in the first rank of naturalistic authors along with Stephen Crane, Jack London, and Theodore Dreiser. Ambrose Bierce is also sometimes considered a naturalist. Norris' most well known novel, McTeague, was committed to film by Eric von Stroheim in a lost epic called Greed (1924). The surviving footage comprises only a fraction of von Stroheim's original high-reaching ambitions for the film. Although I have never seen Greed, I was reminded of descriptions of it when I saw There Will Be Blood in 2007. That film was based on Oil! by Upton Sinclair, a muckraker and naturalist himself. By the way, Frank Norris' brother, Charles Gilman Norris (1881-1945), and sister-in-law, Kathleen Norris (1880-1966), were also novelists.

Weird Tales reprinted just one Frank Norris story. It came in the Summer 1973 issue when Sam Moskowitz was trying to recapture some old stories for his updated version of the magazine. As Moskowitz noted, Norris wrote several stories of the supernatural, despite his naturalistic tendencies. They included "The Ship That Saw a Ghost," "Grittir at Thorhall-stead," and "The Guest of Honor," published in Everybody's Magazine in July-August 1902 and reprinted in the fiftieth anniversary issue of Weird Tales in 1973.

Frank Norris' Story in Weird Tales

"The Guest of Honor" (Summer 1973, originally in The Pilgrim Magazine, July/Aug. 1902)

|

| The image was an effective one, however, in the era of monopolies. Here, the octopus represents the railroad monopoly. |

|

| Here, Standard Oil. |

|

| Finally, an illustration that is a little more representative of the original story. |

|

| I'll close with a more pleasing image, a cover illustration for The Golden Book for November 1926 with Frank Norris' byline on the left. |

Text and captions copyright 2012 Terence E. Hanley

Friday, October 26, 2012

Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933)

Fine Artist, Illustrator, Short Story Writer, Novelist, Playwright, Children's Book Author

Born May 26, 1865, Brooklyn, New York

Died December 16, 1933, New York, New York

Robert W. Chambers lived the kind of life any aspiring writer might envy. Talented, popular, and prolific, he wrote nearly one hundred books and used the proceeds to fund a lavish estate, a sizable art collection, an active club life, frequent trips abroad, independent wealth, and plenty of leisure time. He was an outdoorsman, a lepidopterist, a collector, an expert on certain antiquities, and in his early years, a very successful artist and illustrator, counting Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) and other artists and writers among his friends. Many of Chambers' stories were adapted to film in his lifetime and after. Chambers' wife, French-born Elsa Vaughn Moller, called "Elsie" and daughter of a European diplomat, bore him one son, Robert Edward Stuart Chambers. The younger Chambers, who also went by the name Robert Husted Chambers (1899-1955), followed in his father's footsteps as a writer. The Chambers family also included Chambers' brother, the New York architect Walter Boughton Chambers (1866-1945), who designed landmarks in his native city and other northeastern states.

Wealth, talent, fame, family--it all added up to a great success, yet, as far as I know, there has never been a book-length biography of Robert W. Chambers. And in the minds of many, Chambers squandered his talent on popular novels produced at a rapid pace and settling somewhere below the ken of literature. "Stuff! Literature!" Robert W. Chambers scoffed in a 1912 interview. "The word makes me sick!" His disdain for literary endeavor may have been the fox talking about the grapes. Either way, it assured that his work would become dated and seldom read in later years. In his time, he was called "the Shopgirl Scheherazade" and "the Boudoir Balzac." Today, Chambers' reputation rests almost solely on a single book, his second, entitled The King in Yellow, published in 1895.

In his survey of the genre, H.P. Lovecraft wrote--in his "Supernatural Horror in Literature" (1)--two long paragraphs on Chambers. I'll quote them in their entirety here:

Very genuine, though not without the typical mannered extravagance of the eighteen-nineties, is the strain of horror in the early work of Robert W. Chambers, since renowned for products of a very different quality. The King in Yellow, a series of vaguely connected short stories having as a background a monstrous and suppressed book whose perusal brings fright, madness, and spectral tragedy, really achieves notable heights of cosmic fear in spite of uneven interest and a somewhat trivial and affected cultivation of the Gallic studio atmosphere made popular by Du Maurier’s Trilby. The most powerful of its tales, perhaps, is "The Yellow Sign," in which is introduced a silent and terrible churchyard watchman with a face like a puffy grave-worm's. A boy, describing a tussle he has had with this creature, shivers and sickens as he relates a certain detail. "Well, sir, it's Gawd's truth that when I 'it 'im 'e grabbed me wrists, sir, and when I twisted 'is soft, mushy fist one of 'is fingers come off in me 'and." An artist, who after seeing him has shared with another a strange dream of a nocturnal hearse, is shocked by the voice with which the watchman accosts him. The fellow emits a muttering sound that fills the head like thick oily smoke from a fat-rendering vat or an odour of noisome decay. What he mumbles is merely this: "Have you found the Yellow Sign?"

A weirdly hieroglyphed onyx talisman, picked up in the street by the sharer of his dream, is shortly given the artist; and after stumbling queerly upon the hellish and forbidden book of horrors the two learn, among other hideous things which no sane mortal should know, that this talisman is indeed the nameless Yellow Sign handed down from the accursed cult of Hastur—from primordial Carcosa, whereof the volume treats, and some nightmare memory of which seems to lurk latent and ominous at the back of all men's minds. Soon they hear the rumbling of the black-plumed hearse driven by the flabby and corpse-faced watchman. He enters the night-shrouded house in quest of the Yellow Sign, all bolts and bars rotting at his touch. And when the people rush in, drawn by a scream that no human throat could utter, they find three forms on the floor—two dead and one dying. One of the dead shapes is far gone in decay. It is the churchyard watchman, and the doctor exclaims, "That man must have been dead for months." It is worth observing that the author derives most of the names and allusions connected with his eldritch land of primal memory from the tales of Ambrose Bierce. Other early works of Mr. Chambers displaying the outré and macabre element are The Maker of Moons and In Search of the Unknown. One cannot help regretting that he did not further develop a vein in which he could so easily have become a recognised master.

That's a lot to digest in a single blog entry, but it's worth reading for a number of reasons. First, it's obvious that Lovecraft drew on The King in Yellow in general and on "The Yellow Sign" in particular for concepts and atmosphere for his own weird fiction. Second, it's illuminating to read of the lineage of Chambers' "names and allusions," which can be traced backward to Bierce and forward to Lovecraft and his acolyte, August Derleth. Third, it's very interesting to read Lovecraft's criticisms of the older man Chambers:

Very genuine, though not without the typical mannered extravagance of the eighteen-nineties, is the strain of horror in the early work of Robert W. Chambers . . . [emphasis added].

One cannot help regretting that he did not further develop a vein in which he could so easily have become a recognised master [again, emphasis added].

Those two criticisms, which open and close Lovecraft's discussion of Chambers, can just as easily be leveled at Lovecraft himself. In fact they sometimes have been.

* * * * *

You can read about Robert W. Chambers elsewhere on line or at the library. (The New York Times wrote of him extensively in his time. You might start by reading his obituary, dated December 17, 1933, page 36.) I'll skip the biographical details and write just a little more. First, as Lovecraft wrote, Chambers authored several works of horror, fantasy, and science fiction. (2) Second, he also wrote a book called Police!!! (1915), which may very well have contained the first cryptozoological fiction ever set to print. (3)

Cryptozoology, founded in the nineteenth century but not named until the twentieth, is the science or semi-science of unknown creatures. Its recognized founder was Antoon Cornelis Oudemans (1858-1943), a Dutch zoologist who attempted to describe and classify unknown creatures in his book The Great Sea Serpent (1892). Robert W. Chambers--Oudemans' junior by only seven years--was an enthusiastic entomologist and lepidopterist; his credentials as a science-minded author would appear firm. The point of this is that cryptozoological fiction would not have been likely before science was brought to bear on what would previously have been the stuff of legend or folklore. It's also unlikely that anyone would have written stories on a sensationalistic topic such as cryptozoology before there was a popular press on an industrial scale. I guess I should ask the question then: Can anyone offer another candidate for the first fiction in the young field of cryptozoology?

Notes

(1) Literature? "Stuff!" Chambers might say.

(2) A story called "The Repairer of Reputations" opens Chambers' 1895 collection, The King in Yellow. Set in 1920, the story alludes to recent events, including the administration of a President Winthrop and recent victory in a war with Germany. Winthrop is close enough to Wilson, and of course the United States and Germany were involved in a little tussle ending in 1918. You might say that science fiction blends into prophecy in Chambers' tale. Mostly, though, his projections are simply nonsense.

(3) There is also a hint of forensic entomology in one of the stories.

Robert W. Chambers' Stories in Weird Tales

"The Demoiselle d'Ys" (Aug. 1928)

"The Sign of Venus" (Summer 1973, originally in Harper's Magazine, Dec. 1903)

"The Splendid Apparition" (Winter 1973, originally in In Search of the Unknown, 1904)

|

| A drawing of the King in Yellow, created by Robert W. Chambers himself, that rare combination of accomplished writer and accomplished artist. |

|

| Jack Gaughan, the cover artist for the Ace Books edition of 1965, followed Chambers' model closely. |

|

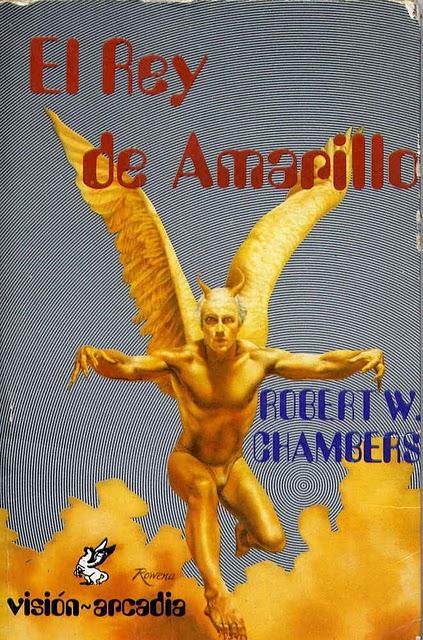

| This Spanish-language version features an Op Art background to Rowena Morrill's illustration. |

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley