I have been reading The Revolt of the Masses by José Ortega y Gasset. It's a somewhat difficult book, not because of its ideas--the author mostly stays away from dense philosophical musings--but because of its style. Ortega y Gasset (or maybe his translator) wrote in a somewhat thick, cumbersome, even archaic, way. Despite its Latin origins, there is little flourish here. In any case, this is a valuable book, especially for those interested in freedom and tyranny. Eric Hoffer must have read it keenly in formulating his own work, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (1951).

Since writing about the monster of our times, I have been on the lookout for any comparisons in writing between the mass-man (what Eric Hoffer called "the true believer") or that creation of the mass-man, the Moloch State, and the monsters of the past or of science. After reading more than a hundred pages of The Revolt of the Masses, I finally came upon this:

The mass says to itself, "L'État, c'est moi," (1) which is a complete mistake . . . . But the mass-man does in fact believe that he is the State, and he will tend more and more to set its machinery working on whatsoever pretext, to crush beneath it any creative minority which disturbs it . . . .

The result of this tendency will be fatal. Spontaneous social action will be broken up over and over again by State intervention; no new seed will be able to fructify. Society will have to live for the State, man for the governmental machine. And as, after all, it is only a machine whose existence and maintenance depend on the vital supports around it, the State, after sucking out the very marrow of society, will be left bloodless, a skeleton, dead with that rusty death of machinery, more gruesome than the death of a living organism. (2)

In other words, the State, first a lethal machine, then a vampire, will come to its end as one of the walking dead. The Revolt of the Masses was published in 1932, after Communists had seized power in Russia and Fascists in Italy, but before Hitler rose to be Führer of the German people. Statism was then powerful and on the rise. Nonetheless, Ortega y Gasset seems to have predicted the end of the Soviet Union in his description of a "bloodless" State, "dead with the rusty death of machinery." We can all be forgiven our lack of sympathy upon its demise.

Ortega y Gasset traced the development of his mass-man to the nineteenth century, as I did in my many postings from last year. (It's nice when your theorizing is confirmed by an accomplished author and thinker.) Last week, France, and by extension, all of Western civilization, was attacked by that mass-man, in this case a group of Islamists. (3) The adjective so often used to describe this particular brand of mass-man is "medieval." That word trips readily from the lips for different reasons, I think. One is that it seems to be true. Islam is after all literally medieval, having come from the seventh century. Another is that, by labeling Islam as medieval, people of a certain political persuasion can attempt to link it to those who oppose them. As further evidence of that, I'll point out that radical Islam is also frequently described as "conservative" or "fundamentalist." I would contend that Islamism is not in fact medieval but is entirely modern, for it is a mass movement carried forward by masses of true believers. Like Communism, Fascism, and Nazism, Islamism, as a form of statism and totalitarianism, is an outgrowth of the nineteenth century that came into full fruition only in the very bloody twentieth. Like Communists, Fascists, and Nazis, Islamists devote themselves to a holy cause for which they are willing to give up everything, including and especially their lives. As such, they are not men of the past--not "medieval" or "conservative"--but men of the glorious future. (4) Witness their use of up-to-date technology, including the Internet, social media, cell phones, and current military weapons and techniques. Further, the caliphate, like the Communist "Worker's Paradise" and the Nazi "Thousand-Year Reich," is a statist and totalitarian utopia, in other words, a work of the future. But like all utopias, it's a pipe dream. Unfortunately, those who know that human beings are and by rights free are again and again made to pay for that dream with their rights, their freedoms, their property, and their lives. (5)

Notes

(1) A more recent statement of that belief: "Government is the only thing we all belong to," from the Democratic national convention of 2012. Ortega y Gasset called the United States a paradise of the mass-man. But here I think we can make a distinction between his mass-man and Hoffer's true believer. The true believer is a man of action. He is also very often a man of great physical courage, despite the loathsome beliefs that animate him. The idea that "Government is the only thing we all belong to," symbolized by a hot-chocolate-sipping pajama boy, is, on the other hand, a creed of inaction, passivity, cowardice, and failure. More to the point, it's just plain stupid.

(2) From The Revolt of the Masses by José Ortega y Gasset (Norton, 1957), pp. 120-121.

(3) There may be millions of people today saying, "Je suis Charlie," but only a dozen lost their lives standing for their freedom and ours. The rest of us can't really exalt ourselves too much, and we should be humble in any of our pronouncements. It's easy for the living to claim courage, especially when they're standing in a crowd of millions. The cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo stood alone.

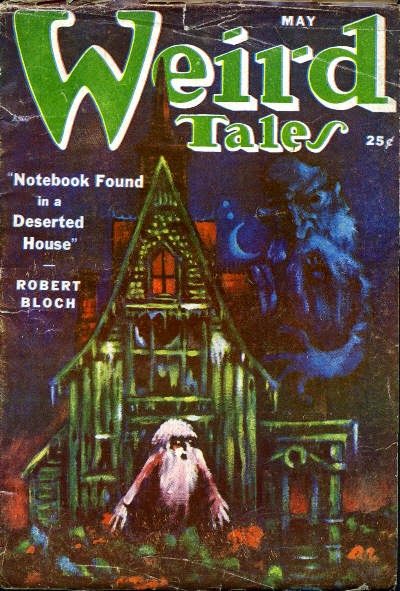

(4) In terms of genre fiction, they are not the subjects of fantasy, horror, or weird fiction, all of which are of the past, but of science fiction, the genre of the future. Here's a strong bit of evidence: Coincident to the attacks last week, Charlie Hebdo featured Michel Houellebecq, author of the new novel Soumission, on its cover. Set in 2022, Soumission is--as I understand it--not so much a dystopian novel as a satiric one about an Islamic takeover in France. Nonetheless, every dystopia must have a beginning. It's worth noting that in the book, the Islamists join forces with their socialist peers in parliament to form a government. Despite their differences, the Islamist and the socialist--both men of the future and both utopian and statist in their vision--would seem natural allies. That seems to be the case in our world today, not only in Europe but also here in the United States. Eric Hoffer noted a natural affinity among true believers, regardless of whether they call themselves Communists or Nazis. The difference here is that Islamists are men of action, fired by their belief in a holy cause. Contemporary socialists, on the other hand, are, at best, men of words only, having grown fat and complacent after so many years on the thrones of government and academia. There is little fire in them, least of all any holy fire. Socialists might think they can control Islamists. The man of words always believes there will be a special place for him when the revolution comes. More likely they would go down like White Russians or Mensheviks, for the belief with fire in it will always win out over the one without.

(5) When I was young and watched Jonny Quest or James Bond, I wondered where Dr. Zin or Goldfinger or Blofeld found his henchmen, those hoards of anonymous men (often masked) who so willingly die for his cause. The answer became obvious as I grew older, for I realized that a man might kill or risk his life for money, power, or prestige, but he won't die for a cause unless he believes in it. In the real world, Auric Goldfinger would be out of luck, for he would not find men who would give up their lives for his cause, for his cause is his alone. If he wants men to give up their lives for a cause, it has to be a cause to which they can all subscribe, in other words, a holy cause, a mass movement.

Revised on January 15, 2015.

Copyright 2015, 2023 Terence E. Hanley