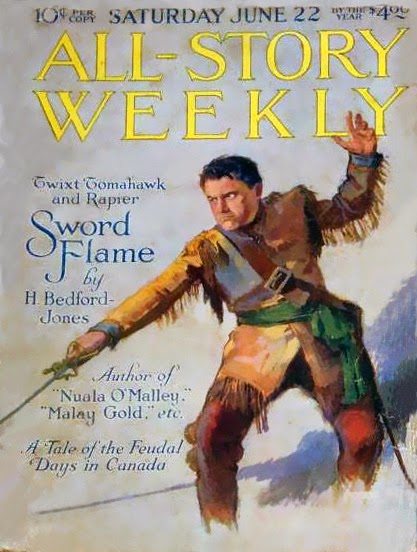

So the careers of A. Merritt and Francis Stevens have some similarities and possibly some connections. The two authors may have met early in their careers, when she was working as a secretary at the University of Pennsylvania and he was a journalist at the Philadelphia Inquirer and The Sunday Supplement and/or The Sunday American Magazine, forerunner to The American Weekly. (1) Both had their first stories published in All-Story Weekly in 1917, and both wrote almost exclusively for the Munsey magazines (Argosy and All-Story) for several years. There was even a time when readers thought that "Francis Stevens" was a pseudonym of A. Merritt. They were only half right, for "Francis Stevens" was actually the pseudonym of Gertrude Barrows Bennett. One difference between Merritt and Stevens is that he became well known and very wealthy. She was neither.

It's reasonable to assume that Merritt was in contact with Gertrude Barrows Bennett. His first story in Famous Fantastic Mysteries or Fantastic Novels Magazine--two titles that reprinted stories from the old Munsey magazines--was "The Moon Pool," the lead story in the first issue of Famous Fantastic Mysteries, dated September-October 1939. Stevens' first story reprinted in those magazines was "Behind the Curtain" in Famous Fantastic Mysteries for January 1940. I have lost track of the source that says Merritt persuaded Mary Gnaedinger, the editor of Famous Fantastic Mysteries and Fantastic Novels Magazine, to reprint Francis Stevens' stories. I wonder now if he let Gertrude Barrows Bennett know about these new markets for her stories or if he secured payment for her for their reprinting. In any case, A. Merritt died of a heart attack on August 21, 1943, at his winter home in Indian Rocks Beach, Florida. Gertrude Barrows Bennett followed him to the grave in 1948. Nonetheless, Mary Gnaedinger continued reprinting their work. Six of Gertrude's thirteen stories were reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, Fantastic Novels Magazine, or Famous Fantastic Mysteries Combined with Fantastic Novels Magazine from 1940 to 1950. At least thirteen of Merritt's stories were so honored. His were also reprinted in Amazing Stories, Avon Fantasy Reader, Fantastic, Leaves, Satellite Science Fiction, Science and Invention, Science Fiction Digest, and Super Science and Fantastic Stories, as well as many collections and anthologies over the years.

Both A. Merritt and Francis Stevens had just one story published in Weird Tales, both in the 1920s. Merritt's contribution, "The Woman of the Wood" (Aug. 1926), was voted by readers the most popular story in the issue in which it appeared, for the entire year of 1926, and of all stories published from 1924 to 1940. It was reprinted in January 1934 and was again voted the most popular story in that issue. (2) Stevens' lone contribution, "Sunfire" (July-Sept. 1923) was published before readers were polled for their favorite stories. With it, her writing career came to an end, while Merritt's continued to the end of his life, although his last story published in his lifetime was in 1936, shortly before he became editor of The American Weekly in 1937 (3).

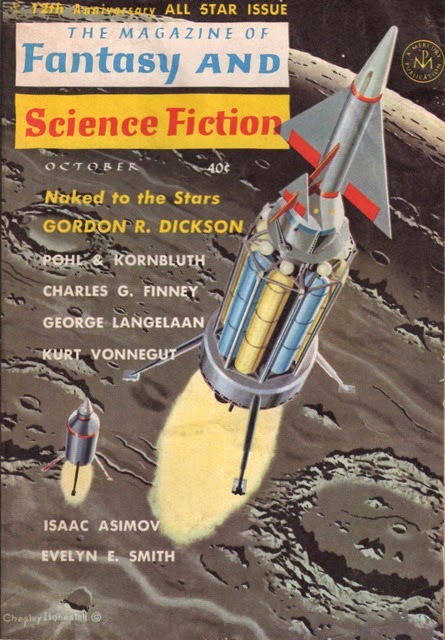

As further evidence of Merritt's popularity, in 1938, Argosy polled its readers for their favorite story in the fifty-eight-year history of the magazine. The winner was "The Ship of Ishtar" from 1924. Argosy proceeded to reprint Merritt's story and confessed that it had paid him the highest word-rate of any its authors. The editor wrote: "This only proves he was worth it!" (4) More than a decade later, in December 1949, Merritt had a magazine published with his name in the title, A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine. Mary Gnaedinger was the editor for five issues dated December 1949 to October 1950, when the magazine came to an end. Vargo Statten Science Fiction Magazine (1954) and Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine (1977-present) later fell into the category of magazines named for authors.

A. Merritt was and is a very popular writer, and his stories have seldom if ever been out of print. According to Sam Moskowitz, Avon Publications estimated that its re-printings of Merritt's stories had sold four million copies as of 1959. (5) Merritt's stories have been reprinted many times in many languages, including English, of course, as well as French, Italian, and German. They have also been adapted to the movies in Seven Footprints to Satan (1929) and two adaptations of "Burn, Witch, Burn!", The Devil Doll (1936) and Muñecos infernales (1961). He is supposed to have been an influence on Francis Stevens and H.P. Lovecraft, or they were an influence on him, or each other, or some combination of influences, one upon another, for which no one seems to have offered very much evidence. (6) Suffice it to say, Merritt's stories "are among the most famous titles in the canon of fantastic literature." (7) A. Merritt was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 1999.

A. Merritt's Story, Essay, & Letters in Weird Tales

"The Moon Pool" (Aug. 1926; reprinted Jan. 1934)

Letter to "The Eyrie" (Oct. 1929)

Letter to "The Eyrie" (Oct. 1934)

Letter to "The Eyrie" (Nov. 1935)

"How We Found Circe" (Winter 1973; originally in The Story Behind the Story, 1942)

Further Reading

There is much to read about A. Merritt on the Internet and in those ancient artifacts known as books, including:

- "The Marvelous A. Merritt" in Explorers of the Infinite by Sam Moskowitz (Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1963), pp. 189-207.

- Introduction by Sam Moskowitz to "The Moon Pool" by A. Merritt in Under the Moons of Mars: A History and Anthology of "The Scientific Romance " in the Munsey Magazines, 1912-1920 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970), pp. 137-138.

- A. Merritt: Reflections in the Moon Pool by Sam Moskowitz (1985)

Notes

(1) Gertrude Barrows Bennett had arrived in Philadelphia in 1909 or 1910, either newly married or newly widowed. A. Merritt left Philadelphia in 1912 for New York City, but I can't say that he cut ties to his former city. It's worth noting that one of the characters in Stevens' story "Sunfire" (1923) is a "war-correspondent and a writer of magazine tales." Named Alcot Waring, he is described as a "vast mountain of flesh . . . obese, freckle-faced, with small, round, very bright and clear gray eyes" (The Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy, p. 348). I have seen two photographs of Merritt but have never read a description of him. He doesn't appear to have been a small man, but he may not have been Alcot Waring-sized either. Like Waring, Merritt spent some time in Latin America, at least as a visitor and maybe as an explorer.

(2) Merritt also had an essay in the magazine, "How We Found Circe," in a later incarnation, Winter 1973.

(3) At the time, The American Weekly, the Sunday magazine of the Hearst newspaper chain, claimed "the largest circulation of any periodical in the world" according to Sam Moskowitz. (Source: Moskowitz's introduction to "How We Found Circe" in Weird Tales, Winter 1973, p. 26.) Considering his new responsibilities, we can't blame Merritt for not writing in the field of fantasy after 1937.

(4) Quoted in "The Marvelous A. Merritt" by Sam Moskowitz in Explorers of the Infinite (1963), p. 190.

(5) Explorers of the Infinite, p. 206.

(6) In "The Moon Pool" by Merritt (published June 22, 1918), there is a "moon-door." In The Heads of Cerberus by Stevens (published August-October 1919), there is a "moon-gate." If these things are evidence of influence, one upon another, then Merritt would seem the influence in this case. But how far does anyone want to go with something like that?

(7) Sam Moskowitz in his introduction to "The Moon Pool" by A. Merritt in Under the Moons of Mars: A History and Anthology of "The Scientific Romance " in the Munsey Magazines, 1912-1920 (1970), p. 137.

|

| Abraham Merritt (1884-1943) |

Text and captions copyright 2015, 2023 Terence E. Hanley