According to Robert Weinberg and his co-editors (or Mr. Weinberg alone), C. Hall Thompson's stories in Weird Tales were among the first Cthulhu stories "written by an author who was not personally invited to join the fun by Lovecraft." According to editor Charles M. Collins, Thompson was "catapulted to fame" after his work appeared in Weird Tales, with "Spawn of the Green Abyss" receiving "tremendous acclamation" and "hailed as out Lovecrafting the old master himself." All of that appears to have been too much for August Derleth, who pressured Weird Tales to quit publishing Thompson's Lovecraftian stories. This in effect seems to have silenced the younger author, who spent the remainder of his career writing Westerns and crime/detective stories. Thompson may have his revenge, though. His four stories have been reprinted again and again, and if he was indeed the author behind the Arthur Pendragon stories, then he has also been hailed as the creator of two of the best Cthulhu stories of the post-Lovecraft era. These, too, have been reprinted, most recently in Acolytes of Cthulhu (2014). Derleth's byline is missing from that book by the way.

But was Thompson Pendragon? No one knows and no one may ever know. A user named Druidic on the website Thomas Ligotti Online seems to think so, though, and the more I look into the controversy, the more I think things fit. Still, the evidence is circumstantial only. I haven't found anything conclusive.

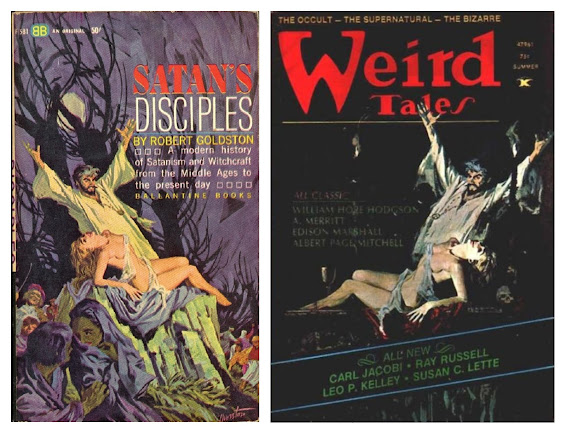

In going about all of this, I first looked at C. Hall Thompson's stories in Weird Tales. Here is what I found . . .

In going about all of this, I first looked at C. Hall Thompson's stories in Weird Tales. Here is what I found . . .

Thompson's four stories were:

- "Spawn of the Green Abyss" (Cover story, Nov. 1946)

- "The Will of Claude Ashur" (July 1947)

- "The Pale Criminal" (Sept. 1947)

- "Clay" (May 1948)

Of these, only "The Will of Claude Ashur" touches directly on what is now called the Cthulhu Mythos. (That's Derleth's term. I'm not sure that we should use it, but it's too late to do anything about it now.) The others are Lovecraftian to one degree or another, but they could easily take place in a non-Cthulhian universe.

Three of the four are set in the northeastern United States. Only "The Pale Criminal" takes place beyond American shores, in Germany. Of the three stories set here in this country (I write from the cold, snowy Midwest), two are based in New Jersey with side trips to other places. One, "Clay," takes place in Lovecraft's beloved New England. If you're writing while under the influence of Lovecraft, I can see setting your stories in New England. That was his country. But to set your stories in New Jersey seems a little odd to me--unless New Jersey forms a part of your own region, one that you might wish to mythologize in the same way that Lovecraft mythologized New England. Well, C. Hall Thompson was born in Philadelphia and lived in Pennsylvania--like New Jersey, a Mid-Atlantic state--for all or most of his life. (1, 2) In contrast, Arthur Porges, another candidate for the Pendragon title, was from the Chicago area and lived, I think, in California for a good many years.

All four of Thompson's stories have Lovecraftian elements, but they also have conventional gothic elements. There are locked rooms, locked chests, secret books, and hidden manuscripts. There are also ancient curses, forbidden rites and lore, twin or switched identities, cases of possession and malign influence cast by supernatural forces, all of which culminate in ghastly deaths or unfortunate fates visited upon the main characters. As in so many gothic stories--maybe all gothic stories--much of the action in Thompson's work takes place in lonely and forbidding houses. In "Spawn of the Green Abyss," it's called Heath House, located close to a town "sprawled on a forlorn peninsula off New Jersey's northeastern coast." (3) In "The Will of Claude Ashur," the house is Inneswich Priory, not a priory at all but a private home, also located in New Jersey. In "The Pale Criminal," the house is a castle called Zengerstein, which looms on the edge of the Black Forest. (4) Finally, the action in "Clay" takes place at Wickford House, an asylum for the insane located somewhere in northern New England. There is in fact a lot of insanity or presumed insanity in Thompson's weird fiction, but--younger by more than a generation than H.P. Lovecraft--Thompson had a different angle on mental illness, one that would have been in vogue in postwar America.

To be continued . . .

Notes

(1) On the other hand, if you're from Pennsylvania and want to mythologize a place, why wouldn't you choose your own place to mythologize?

(2) I wouldn't rule out that Thompson served in the military during or right after World War II. His first known published story was "The Shanghaied Ruby" in the Winter 1945-1946 issue of Fight Stories. That would have been just right for a man separating or soon to separate from the military.

(2) I wouldn't rule out that Thompson served in the military during or right after World War II. His first known published story was "The Shanghaied Ruby" in the Winter 1945-1946 issue of Fight Stories. That would have been just right for a man separating or soon to separate from the military.

(3) That sounds like Sandy Hook to me, but I'm no Easterner. There are beaches at Sandy Hook, and I wonder if it was a tourist spot for Philadelphians in Thompson's day. There are also military installations at Sandy Hook. Could Thompson have been stationed there?

(4) Or could Thompson, if he was in the military, have been stationed in postwar Germany? Maybe not, as "The Pale Criminal" seems an imitation of a story by Poe and not based on anything from real life.

Copyright 2019, 2023 Terence E. Hanley