I wasn't going to interrupt my series on Earl Peirce, Jr. I was going to keep writing it straight through to the end, which is still a couple of weeks off at the current rate. But then I saw something yesterday that put me over the edge.

I saw a man driving a Jeep.

Alone.

With the top down.

And the doors off.

With the wind whipping all around him and through his vehicle.

And he was wearing a mask.

It's not just a Jeep Thing. Every day, I see people driving, with their windows up or down, or bicycling, or walking, in the breeze, in the fresh air, in the bright, hot, ultraviolet-y sunshine--and they wear masks. They're alone, and they wear masks. They're with their husbands or wives, with whom they presumably live, sleep, eat, and make love, and they wear masks. They could be astronauts in quarantine after a moon-landing--they could be the scientists in The Andromeda Strain, scrubbed and sterilized to the marrow--they could be the Bubble Boy inside his impervious plastic membrane--and they would still wear masks.

The operative part of coronavirus is virus, a thing--living, non-living, or somewhere in between--that is both discoverable and describable by science. Our superstitious acts--knocking on wood or throwing a pinch of salt over our shoulders--are of no use. They do nothing. To use a science-y kind of word, they are inefficacious. Likewise, the coronavirus does not exist or act in accordance with superstition. It does not go around in clouds, vapors, gases, or waves, like the poisonous tail of a world-ending comet, or a fog of mustard gas creeping over a Belgian battlefield, or a strange mist that engulfs you like the one in The Incredible Shrinking Man, leaving you coated all over the way a kindergartner is after crafting with sparkles and glue. It is a virus, and it is subject to the laws of nature, not the vagaries of superstition. We live in a world full of people who claim an absolute belief in science and an equally absolute disdain for superstition. In actuality, most people feed at a buffet in which both are offered and they take their pick. A little of this, a little of that . . .

A comet is crossing our skies this week. Called NEOWISE, it was discovered on March 27, 2020, the week before coronavirus deaths in the United States jumped from the hundreds into the thousands. Coincidence? I don't think so. Not when you realize that comets have been bringers of doom and disaster for as long as there have been people. It happened in 1832 with Biela's Comet. If you don't know that the world ended then, it's only because all records were wiped out in the disaster. The same comet came back in 1872 and the world ended again. In 1910, the French astronomer and science fiction author Camille Flammarion (1842-1925) predicted that if the Earth should pass through the tail of Halley's Comet, cyanogen gas could impregnate our atmosphere, thereby snuffing out all life here. I don't know which hat Flammarion was wearing when he made that prediction, whether it was his stargazer hat or his fantasist hat. Maybe he made this one himself from tinfoil. In any case, I don't remember that the world came to end in 1910, but then that was way before my time.

By the way, that's the second time Flammarion's name has come up in this blog in the last month. That's pretty good for a guy who has been dead for nearly a century and whom nobody remembers much anymore.

I'm not sure how Flammarion survived all of the cyanogen gas that swept the planet. Maybe he hid in a cave like we're all doing right now and like a "strange sect" in Georgia did on the night of May 18-19, 1910, as the comet made its deadly pass. (1) Those people were pikers, though. They may have had to deal with great clouds of cyanogen gas, but that's nothing compared to coronavirus. I heard that coronavirus can actually dissolve rubber. It happened to a fighter pilot over New Mexico when he flew through a cloud of it. His mask dissolved and he ended up crashing his airplane and dying. That's what I heard.

We don't know how many fatalities there were from Halley's Comet in 1910. We didn't keep good numbers back then. Not like today. Not like in Florida, where a man who was killed in a motorcycle crash the other day is rightly counted as a coronavirus victim because he had the coronavirus when he crashed. That's what Dr. Florida Man told us. I quote: "But you could actually argue that it could have been the COVID-19 that caused him to crash." Too bad Dr. Florida Man wasn't around in 1910 to count the victims. Then we would know. Instead all we have is the case of forty-eight-year-old Jacob Haberlach of Evansville, Indiana, who keeled over from a heart attack while trying to get a look at the comet. (2) The score so far: Coronavirus 10 billion, Halley's Comet 1.

If this is science, I guess we will go on having clouds and mists, vapors and waves, fogs and gasses, cloaking the planet in a deadly miasma but rendered completely harmless by pieces of cloth worn over our faces. Or really just parts of our faces because who ever breathes through their nose? You don't need a mask there.

I don't know how we're ever going to get through all of this.

I don't know how we're ever going to get through all of this.

Notes

(1) "Georgia Sect in Cave Awaiting End of World," York Daily (York, Pennsylvania), May 19, 1910, p. 1.

(2) "Comet Causes Heart Disease," York Daily (York, Pennsylvania), May 19, 1910, p. 1. Yes, they're from the same source.

Comet Madness!

"But wonders and wild fancies had been, of late days, strangely rife among mankind [. . . ]."

--Edgar Allan Poe

|

| In its issue of December 1839, Burton's Gentleman's Magazine printed Edgar Allan Poe's tale "The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion." The tale is brief. It takes the form of a dramatic dialogue between the two title characters, one newly arrived in the afterlife, the other a veteran. The newcomer Eiros explains how he got to this place: Earth came in contact with a comet that--tenuous as it was known to be--nonetheless took away all of our planet's nitrogen, leaving everything to "burst at once into a species of intense flame, for whose surpassing brilliancy and all-fervid heat even the angels in the high Heaven of pure knowledge have no name. Thus ended all." Was this the first comet story in fantasy and science fiction? I don't know. Was it the first tale of comet madness? I don't know that either. Let's just call it an introduction and draw from it the epigraph above, which is as true now--or truer--as it was in Poe's day. The illustration by the way is by the Italian artist Alberto Martini (1876-1954). |

|

| This one's even better. There is actual pain, suffering, and destruction going on, though most of the people don't appear to be too worked up over things. One woman is even holding onto her hat as if to lose it would be the greatest of disasters. Taken from the Chicago Tribune, August 9, 1903, this illustration has a now-classic composition with people running around in the foreground while all kinds of terrible things are going on in the background. ("It's a cookbook! It's cookbook!") Basil Wolverton drew a picture almost exactly like it for a story called--appropriately enough--"The End of the World." To see it and others like it, click here. |

|

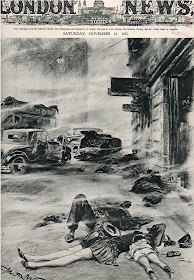

| These are British soldiers "Fighting Foul Fumes and Fiends." They're wearing masks like the ones we're wearing now. The difference is that they faced horrors, many of them almost certain death. What do we face exactly? The date--May 15, 1915--is significant: less than a month before, on April 22, 1915, the Germans used poison gas for the first time as they launched what became known as the Second Battle of Ypres. Note the blurb above the main title, "The Allies' Wonderful Advance on Turkey." It refers, I assume, to the landing at Gallipoli, April 25, 1915. That "advance" turned out to be not so wonderful after all. By the way, American soldiers were gassed during the war, too, among them Robert Jere Black, Jr. (1892-1953), a teller of weird tales. |

|

| There were other veterans of the Great War who contributed to Weird Tales, most notably the editor, Farnsworth Wright (1888-1940), and the co-founder Jacob Clark Henneberger (1890-1969). The war was a seminal event in the creation of the magazine. It's hard to imagine that Weird Tales would otherwise have come about or that it would have had the subject matter from which to draw so many of its stories. There was (and is) a general atmosphere of doom or fate in weird fiction (that's actually close to the meaning of the word weird), also a feeling that we are helpless--or nearly so--in our encounters with the indifferent or even malevolent forces afoot in the universe. In the depths of mass warfare, men might only feel the same things. In December 1939, just three months after World War II began, Weird Tales had its first war cover. The artist was a young Hannes Bok (1914-1964). The cover story is "Lords of the Ice" by David H. Keller (1880-1966). The plot is fanciful (it concerns a nameless dictator's plot to seize the natural resources of Antarctica), but the imagery would have been firm in the memory of its viewers: the man in the doorway could easily have stepped out of a trench in Flanders or France, circa 1915. He's even wearing a mask. (We can safely add Keller's story to the Polar Fiction Database. We might also speculate that the idea of the secret Nazi base in Antarctica was in weird fiction and science fiction before it became a conspiracy theory in what some people think is the real world. But then that's usually the case, not just with conspiracy theories but with all kinds of wacky ideas.) |

|

| As I have already said and as everybody should already know, the coronavirus does not travel around the world in a cloud. You will not encounter it in any such way. Not on foot. Not in your car. Not on your bicycle. And especially not on a boat on the lake. (Unless you're in Michigan. But then only on a motorboat. Being in a canoe protects you from clouds of coronavirus.) What we're living through is not the coming of a comet or a World War I gas attack, and it's certainly not like this scene from The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).* This is actually the first image that came to me as I began seeing people driving around in their cars while wearing masks. This is what I picture must be going on in their imaginations: the approaching cloud of coronavirus . . . The Incredible Shrinking Man was written by Richard Matheson (1926-2013), who also wrote for Weird Tales. His second and last story, entitled "Slaughter House," appeared in the magazine sixty-seven years ago this month, July 1953. Matheson went on to write I Am Legend (1954), the story of a terrible disease that ravages the world and probably the same story that started us off on the road to zombie hordes roaming over the Earth. *Which was released, it so happens, in the month that the Asian Flu pandemic began, February 1957. |

Original text and captions copyright 2020, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

No comments:

Post a Comment