The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has so many interesting things to say, including these two:

The lost-race story [what I have been calling Lost Worlds] is obviously an opportunity for the setting up of imaginary Utopias [q.v.] and Dystopias [q.v.] [. . .]. (p. 736)

It has been suggested, too, that such stories allow exercises in imaginary cultural anthropology [. . .]. (p. 736)

Then the encyclopedists take it back--the way I took things back last time I wrote--pointing out that Lost World utopias and dystopias "are not as common as might be expected" and that in actuality most Lost Worlds stories "are quite straightforward romantic adventures." (p. 736) That seems right to me. I think of Utopia as a progressive or forward-looking genre in which plot and action are secondary to more satiric, intellectual, or high-literary purposes, all fit for publication in a fine hardbound edition and suited for academic or scholarly study. In contrast, the Lost Worlds/science fantasy-type story seems to me more conservative, romantic, and adventurous, essentially a pulp genre meant for popular consumption. Its aims seem simpler. They would appear non-intellectual and even anti-intellectual: Nobody ever accused Edgar Rice Burroughs of being an intellectual, but in our hyper-intellectualized age (which began, I think, in the 1960s and '70s), Burroughs has become a subject for the same kind of academic or scholarly study previously reserved for more literary works. (1)

* * *

The science fiction encyclopedists also write that, in regards to the Lost Worlds genre,

there is more and better cultural anthropology in offworld stories of planetary exploration and colonization of other worlds [q.v.] (mostly postwar), subgenres that largely superseded the lost-race story, than there are in lost-race stories set on earth. [Emphasis added.] (p. 736)

A lot of science fiction history is packed into that little phrase, "subgenres that largely superseded the lost-race story," for it implies that a big part of science fiction came out of the Lost Worlds/science fantasy tradition established by H. Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. That seems right to me, too. If it involves other planets--worlds lost and newly discovered--explorations and odysseys--mysteries and journeys through and in time and space--then it seems likely to have come down to us from the science-fantasy adventures of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. (The dystopian and apocalyptic strain of science fiction would appear to have had different origins. That's another topic still to come in this series.) Burroughs in particular seems to have been an originator of the science-fictional (and utopian) hero, which might have been a new type when he wrote but was based on a far older one, as old as the heroes of ancient Greece. More on that soon, too.

* * *

Here is the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction on Utopias:

It can be argued that all utopias are sf, in that they are exercises in hypothetical sociology [q.v.] and political science. Alternatively, it might be argued that only those utopias which embody some notion of scientific advancement qualify as sf--the latter view is in keeping with most definitions of sf [q.v.]. Frank Manuel, in Utopias and Utopian Thought (anth 1966), argues that a significant shift in utopian thought took place when writers changed from talking about a better place (eutopia) to talking about a better time (euchronia), under the influence of notions of historical and social progress. When this happened, utopias ceased to be imaginary constructions with which contemporary society might be compared, and began to be speculative statements about real future possibilities. It seems sensible to regard this as the point at which utopian literature acquired a character conceptually similar to that of sf. (p. 1260)

That's a long quote, almost long enough for its own blog entry, but it gets to a point, which is that categories seemingly fail and definitions lose their precision as time goes by. Utopia by Thomas More, from 1516, is a Utopia. But is Burroughs' Barsoom, first in print in 1912, also a Utopia? An even larger question: Is science fiction of the twentieth century essentially utopian? Or, can we turn it all around and argue that all Utopias are science fiction, as the encyclopedists suggest in their use of the very passive voice? Maybe Charles Fort's concept of continuity in all things applies: science fantasy, planetary and interplanetary romance, and science fiction as a whole are pulp versions of the damned: "By the damned, I mean the excluded," Fort wrote in 1919, shortly after John Carter projected himself to another planet. And that's how I think of the pulp genres: for decades they were excluded, beneath consideration, beneath contempt, not a part of polite society or worthy of academic study, discontinuous with accepted literature. People might have called pulp magazines rags, but in one sense they weren't rags at all, for rag paper is for finely made books and meant to last. Pulps were for the moment, to be read and discarded, to be found again in the trash or on the train, like Jessica Soames' copy of True Story. Printed on acid paper, they were cheap, designed for decay, meant not to last at all. But in them--perhaps now more than then--are lost and decaying worlds and races, all ready for rediscovery, like Haggard's lost valley of Kukuanaland or Burroughs' decaying world of Barsoom. But the pulp genres did and still do lie along a continuum, or more accurately exist in a medium in which all touch and intermingle with all, in which all boundaries are lost. Lost Worlds are Utopia is science fiction is speculative fiction is literary fiction and so on and on . . .

* * *

It seems to me that in his Lost Worlds stories, of which the Mars books are just one iteration, Burroughs didn't actually write utopian fiction. I think that the definition of Utopia is--like Jabba the Hutt--too broad and flabby. I think that, properly speaking, a utopian story is one concerning a perfect or idealized society. (2) A mere fantasy--even in the form of a Lost Worlds story or some exploration of cultural anthropology--isn't really utopian, for if it is, then all of high fantasy and about half of science fiction is subsumed into Utopia (instead of the other way around). If a word can mean anything, then doesn't it really mean nothing at all? Anyway, in writing their stories of Lost Worlds and cultural explorations, these authors seem pretty clearly not to have had utopian aims. I don't think we should put those aims on them. Instead, I think we should keep our definitions narrow and admit that there are far fewer utopian stories than what some theorists would have us believe. Nonetheless, Utopia seems to have passed into science fiction by way of Lost Worlds and science fantasy . . .

To be continued . . .

Notes

(1) Witness "Utopia in the Pulps: The Apocalyptic Pastoralism of Edgar Rice Burroughs" by Michael Orth in Extrapolation, Vol. 27, No. 3, 1986.

(2) It's worth noting here that ideal and idyll are from the same root, meaning "form" or "appearance," more remotely "to know" or "to see." So, Utopia = ideal society, and Lost Worlds ≈ idyllic society.

|

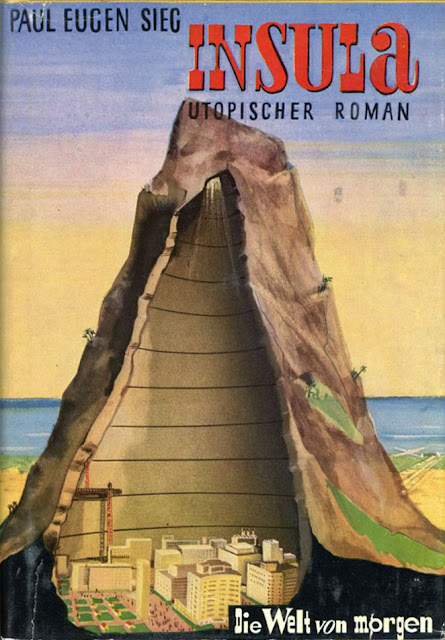

| European languages make a distinction we don't make very well in American English: to us, all book-length works of fiction are called novels. I like the European way: novels are realistic, while romances are fanciful. Here's another linguistic twist: in German, science fiction and utopian stories are tied to each other in the use of the words utopische, utopischen, utopischer, and so on. (I know nothing about the German language, only the words that I see in this place or that.) Here is an example, the cover of Insula by Paul Eugen Sieg (1899-1950), subtitled "Utopischer Roman," presumably "utopian romance," or maybe, loosely, "science fiction novel." Published in 1953, Insula is about a secret volcanic island--a kind of Lost World--inhabited by a scientist living in a secret city, like Captain Nemo or Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Sieg had previously written other science fiction novels, including Detatom (1936), at the core of which is a journey to Mars and the discovery of "remnants of a technically superior high culture." |

|

| The German firm Pabel published hundreds of entries in its Utopia Großband series between 1954 and 1963. Here is the cover of No. 58, from October 21, 1957, featuring a novelization of the American film 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), written by Henry Slesar (1927-2002). The artist was Wolfgang Blaar. |

|

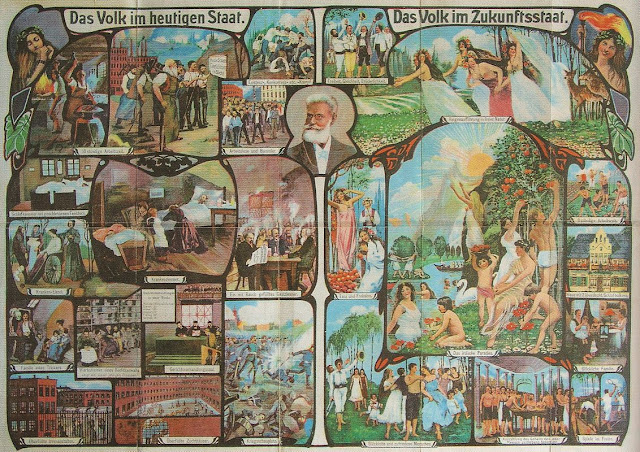

| A final image, one that I have just discovered, "The People in Today's State" versus "The People in the Future State," a German-Romantic vision from 1904 by Friedrich Eduard Bilz (1842-1922). (That's his self-portrait in the middle.) So, above, examples of the Zukunfstroman, a story of the future, or science fiction; and below, an image of Zukunftstaat, the State of the future, or Utopia, in this case an idyllic or pastoral Utopia with imagery that could have appeared--and did appear--on the cover of Weird Tales a generation later, drawn by another German artist, C.C. Senf (1873-1949). (See especially the woman in pink on the center right of the page.) I'll say it again: What every romantic and idealist fails to see is that every Utopia is also a Dystopia, for we are not perfect, we cannot be made perfect, and we will not be harried into perfection nor used as soulless and inhuman building blocks in the construction of someone else's vision of a perfect human society. |

Original text copyright 2021, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

No comments:

Post a Comment