Pages

Monday, February 27, 2023

Colloidal vs. Octopoidal Creatures

Saturday, February 25, 2023

Tentacles on the Cover of Weird Tales

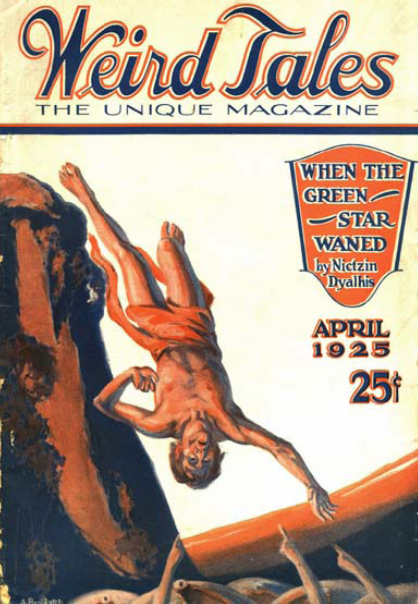

Tentacles may or may not be the appendage of choice for tellers of weird tales, but there have been a few tentacled covers in "The Unique Magazine." I have seven to show here, but most are not quite right. Richard R. Epperly's cover for the first issue of Weird Tales shows tentacles when it should show pseudopodia. The cover illustrating "When the Green Star Waned" by Nictzin Dyalhis shows tentacle-like appendages, but they're actually arms. But then in February 1929, real tentacles arrived in Hugh Rankin's cover illustrating "The Star-Stealers" by Edmond Hamilton. And not only is the creature on the cover tentacled, it also looks likes a starfish, another of those alien-on-Earth type creatures with its slightly disconcerting radial symmetry.

There's a tentacled creature in the upper right of Hannes Bok's cover from March 1940. It's definitely not the star of the show in the way that Matt Fox's alien from November 1944 is. And then we have to skip four decades into the future for Hyang Ro Kim's take on the tentacled alien or monster. Finally, there is the current issue of Weird Tales and its cover by Bob Eggleton.

There are also covers on the themes of snakes, Medusas, and plants, some of which have reaching and entwining tendrils, but I think that tentacles, despite their similarity in appearance to these things, are distinctly different, for they are among the discoveries of science rather than subjects of myth, legends, and folklore. Authors of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries recognized that difference, and I think that's why we have tentacled aliens in fantasy fiction.

I haven't included issues of Weird Tales after the 1980s in my writing on this blog. There are almost certainly tentacle-covers in those issues, but that's a topic for another day.

|

| Weird Tales, March 1940. Cover art by Hannes Bok. The tentacled creature in this cover is a bird-like thing in the upper right. |

|

| Weird Tales, November 1944, with cover art by Matt Fox, a master monster-maker. This cover makes me think of that golden-idol monstrosity recently erected in New York City. I included Fox's cover in an article called "Flying Saucers from Before the Great War," August 16, 2020. |

|

| Weird Tales, Winter 1985, with cover art by Hyang Ro Kim, aka Ro H. Kim. I have written about this cover before, too, on September 30, 2016. |

|

| Finally, the cover for the most recent issue of Weird Tales, what we can accept as the 100th anniversary issue, Number 366, with cover art by Bob Eggleton. |

Thursday, February 23, 2023

Weird Tales, March 1923: Tentacles-Part Two

Before becoming the originator of so much of our science fiction, H.G. Wells trained as a zoologist and biologist. His first book was a textbook of biology called--what else?--Text-Book of Biology, published in 1893. Being in the public domain, every other book published in the nineteenth century is available to us on line. Text-Book of Biology seems to be an exception. Good luck in your search for its full text and illustrations, if there are any.

We recognize the strangeness or alienness of certain types of organisms. Viruses (if they are indeed alive), fungi, and cephalopods confound us. There are some who believe them to be from outer space. As a zoologist or biologist, Wells may have had similar apprehensions, although he may not have been aware of the existence of viruses, which weren't discovered, or at least indicated, until the 1890s. In any case, Wells got in on the nineteenth-century literary habit of writing about giant cephalopods in "The Sea Raiders," a short story from 1896. I'm more interested in his tentacled Martians from The War of the Worlds, serialized in Pearson's Magazine and Cosmopolitan in 1897 and published in hardback the following year.

From Book One, Chapter IV: The Cylinder Opens:

Those who have never seen a living Martian can scarcely imagine the strange horror of its appearance. The peculiar V-shaped mouth with its pointed upper lip, the absence of brow ridges, the absence of a chin beneath the wedgelike lower lip, the incessant quivering of this mouth, the Gorgon groups of tentacles, the tumultuous breathing of the lungs in a strange atmosphere, the evident heaviness and painfulness of movement due to the greater gravitational energy of the earth--above all, the extraordinary intensity of the immense eyes--were at once vital, intense, inhuman, crippled and monstrous. There was something fungoid in the oily brown skin, something in the clumsy deliberation of the tedious movements unspeakably nasty. Even at this first encounter, this first glimpse, I was overcome with disgust and dread.

The Martians' machines also have tentacles:

Seen nearer, the Thing was incredibly strange, for it was no mere insensate machine driving on its way. Machine it was, with a ringing metallic pace, and long, flexible, glittering tentacles (one of which gripped a young pine tree) swinging and rattling about its strange body. It picked its road as it went striding along, and the brazen hood that surmounted it moved to and fro with the inevitable suggestion of a head looking about. Behind the main body was a huge mass of white metal like a gigantic fisherman’s basket, and puffs of green smoke squirted out from the joints of the limbs as the monster swept by me. And in an instant it was gone.

A more thorough description of Martian anatomy and physiology--like that written by a biologist or zoologist, of which H.G. Wells was one--is in Book Two, Chapter II of The War of the Worlds.

* * *

I'll cut to the chase: I think that H.G. Wells' Martians from The War of the Worlds were the prototype of the tentacled or octopoid alien in science fiction, then called pseudo-scientific fiction or scientific romance. From there, tentacles wormed their way into other genres, including science fantasy and weird fiction. I think it was Wells' training as a zoologist and biologist that inspired his leap of imagination. I think he recognized and articulated the alienness of tentacled creatures, more broadly creatures with radial symmetry, and that's why we have such things in our fantasy fiction. It seems unlikely to me that the authors of weird fiction were alone responsible for that development or for initiating that development. I'm not sure that weird fiction as tentacled fiction really works as an idea.

* * *

Anthony M. Rud was the son of two medical doctors. He studied medicine, too, before settling on the writing life. In other words, he, like Wells, received an education in biology, anatomy, physiology, and so on. Writing a story about a giant amoeba would presumably have been within his area of expertise. In "Ooze," he even employed terms such as karyokinesis, protoplasm, nucleolous, and contractile vacuole.

"Ooze," the first cover story in Weird Tales (Mar. 1923), is a proto-science-fictional or science fantasy story. Rud used an older term in his own story. He wrote:

As readers of popular fiction know well, Lee Cranmer's forte was the writing of what is called--among fellows in the craft--the pseudo-scientific story. In plain words, this means a yarn, based upon solid fact in the field of astronomy, chemistry, anthropology or whatnot, which carries to logical conclusion unproved theories of men who devote their lives to searching out further nadirs of fact.

In certain fashion these men are allies of science. Often they visualize something which has not been imagined even by the best of men from whom they secure data, thus opening new horizons of possibility. In a large way Jules Verne was one of these men in his day; Lee Cranmer bade fair to carry on the work in worthy fashion--work taken up for a period by an Englishman named Wells, but abandoned for stories of a different--and, in my humble opinion, less absorbing--type. [Emphasis added.]

Here, then, is direct evidence for the influence of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells on Anthony Rud, and perhaps partly through him, on weird fiction. By the way, Rud used the exact phrase "weird tales" early on in "Ooze," making him the first author in "The Unique Magazine" to include those words together in his or her story.

Despite its octopoid appearance on the cover of Weird Tales, Rud's monster is in fact a giant amoeba. Here's a brief description of the creature:

Rori failed to explain in full, but something, a slimy, amorphous something, which glistened in the sunlight, already had engulfed the man to his shoulders! Breath was cut off. Joe's contorted face writhed with horror and beginning suffocation. One hand--all that was free of the rest of him!--beat feebly upon the rubbery, translucent thing that was engulfing his body!

Another description, from early on in the creature's development:

This amoeba, a rubbery, amorphous mass of protoplasm, was of the size then of a large beef liver.

Then, the scene apparently illustrated on that famous first cover arrives:

Of a sudden her screams cut the still air! Without her knowledge, ten-foot pseudopods--those flowing tentacles of protoplasm sent forth by the sinister occupant of the pool--slid out and around her putteed ankles.

For a moment she did not understand. Then, at first suspicion of the horrid truth, her cries rent the air. Lee, at that time struggling to lace a pair of high shoes, straightened, paled, and grabbed a revolver as he dashed out.

In another room a scientist, absorbed in his notetaking, glanced up, frowned, and then--recognizing the voice--shed his white gown and came out. He was too late to do aught but gasp with horror.

In the yard Peggy was half engulfed in a squamous, rubbery something which at first glance he could not analyze.

Lee, his boy, was fighting with the sticky folds, and slowly, surely, losing his own grip upon the earth!

* * *

Alien invaders came into Weird Tales in April 1925 with Nictzin Dyalhis' novelette "When the Green Star Waned." The author's description of his aliens owes a little to Wells' Martians, I think:

And here we found life, such as it was. I found it, and a wondrous start the ugly thing gave me! It was in semblance but a huge pulpy blob of a loathly blue color, in diameter over twice Hul Jok's height, with a gaping, triangular-shaped orifice for mouth, in which were set scarlet fangs; and that maw was in the center of the bloated body. At each corner of this mouth there glared malignant an oval, opaque, silvery eye.

Note the triangular mouth and the emphasis on the eyes. Note also that the alien is described as "a huge pulpy blob." Later in the story, the things are referred to as "blob-things." So maybe they have similarities not only to Wells' Martians but also to Rud's giant amoeba--and Joseph Payne Brennan's later great slime, inspiration for the Blob of movie fame.

Dyalhis' aliens don't have tentacles, even if the cover illustration shows tentacle-like appendages pointing upward. (That illustration appears to be based on the following passage.) Instead, they have arms:

They, the Things, slowly raised each an arm, pointed at one Aerthon in the group. He, back to them as he was, quivered, shook, writhed, then, despite himself, he slowly rose in the air, moved out into space, hung above the blobs that waited, avid-mouthed. The Aerthon turned over in the air, head down, still upheld by the concentrated wills of the things that pointed . . .

Science fiction still hadn't been adequately named when Dyalhis wrote "When the Green Star Waned." I'm not sure that the term "science fantasy" had appeared yet, either. Nonetheless, I think "When the Green Star Waned" might better be described as science fantasy than as science fiction. The same is true, I think, of "The Call of Cthulhu," from Weird Tales, February 1928. There are science-fictional elements in H.P. Lovecraft's seminal mythos story to be sure, but his purpose was more nearly weird-fictional. The what-ifs of science fiction don't really enter into his storytelling, and the emphasis is on the past, not on the future: "The Call of Cthulhu" is a story of decadence, not of scientific progress.

From "The Call of Cthulhu":

Above these apparent hieroglyphics was a figure of evidently pictorial intent, though its impressionistic execution forbade a very clear idea of its nature. It seemed to be a sort of monster, or symbol representing a monster, of a form which only a diseased fancy could conceive. If I say that my somewhat extravagant imagination yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature, I shall not be unfaithful to the spirit of the thing. A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings; but it was the general outline of the whole which made it most shockingly frightful. Behind the figure was a vague suggestion of a Cyclopean architectural background.

Later, in the encounter with the monster himself:

There was a mighty eddying and foaming in the noisome brine, and as the steam mounted higher and higher the brave Norwegian drove his vessel head on against the pursuing jelly which rose above the unclean froth like the stern of a daemon galleon. The awful squid-head with writhing feelers came nearly up to the bowsprit of the sturdy yacht, but Johansen drove on relentlessly. There was a bursting as of an exploding bladder, a slushy nastiness as of a cloven sunfish, a stench as of a thousand opened graves, and a sound that the chronicler would not put on paper. For an instant the ship was befouled by an acrid and blinding green cloud, and then there was only a venomous seething astern; where--God in heaven!--the scattered plasticity of that nameless sky-spawn was nebulously recombining in its hateful original form, whilst its distance widened every second as the Alert gained impetus from its mounting steam.

If you have read "Ooze," you will remember that there are fish smells and nastiness in that story, too.

* * *

Tentacles (and radial symmetry) are in lots of stories by H.P. Lovecraft. I count them in "The Dunwich Horror" (Weird Tales, Apr. 1929), At the Mountains of Madness (Astounding Stories, Feb.-Apr. 1931), and The Shadow Out of Time (Astounding Stories, June 1936). All involve scientists and scientific investigations of one kind or another, just as in "Ooze." There are tentacles in other stories written by Lovecraft alone and in collaboration with others, too.

* * *

"Shambleau" by C.L. Moore (Weird Tales, Nov. 1933) is a story of science fantasy. Set on Mars, it involves the title character, an alien creature with vampire appetites. She afflicts poor Northwest Smith of Earth with an awful and irresistible desire:

The red folds loosened, and--he knew then that he had not dreamed--again a scarlet lock swung down against her cheek . . . a hair, was it? a lock of hair? . . . thick as a thick worm it fell, plumply, against that smooth cheek . . . more scarlet than blood and thick as a crawling worm . . . and like a worm it crawled.

Smith rose on an elbow, not realizing the motion, and fixed an unwinking stare, with a sort of sick, fascinated incredulity, on that--that lock of hair. He had not dreamed. Until now he had taken it for granted that it was the segir which had made it seem to move on that evening before. But now . . . it was lengthening, stretching, moving of itself. It must be hair, but it crawled; with a sickening life of its own it squirmed down against her cheek, caressingly, revoltingly, impossibly. . . . Wet, it was, and round and thick and shining . . . .

She unfastened the last fold and whipped the turban off. From what he saw then Smith would have turned his eyes away--and he had looked on dreadful things before, without flinching--but he could not stir. He could only lie there on his elbow staring at the mass of scarlet, squirming--worms, hairs, what?--that writhed over her head in a dreadful mockery of ringlets.

And it was lengthening, falling, somehow growing before his eyes, down over her shoulders in a spilling cascade, a mass that even at the beginning could never have been hidden under the skull-tight turban she had worn. He was beyond wondering, but he realized that. And still it squirmed and lengthened and fell, and she shook it out in a horrible travesty of a woman shaking out her unbound hair--until the unspeakable tangle of it--twisting, writhing, obscenely scarlet--hung to her waist and beyond, and still lengthened, an endless mass of crawling horror that until now, somehow, impossibly, had been hidden under the tight-bound turban. It was like a nest of blind, restless red worms it was--it was like naked entrails endowed with an unnatural aliveness, terrible beyond words.

Some readers might find that passage repetitive. I don't see it that way. Instead, I see a building of effect, a characteristic of weird fiction. I think it's an extraordinary piece of writing for a woman in her early twenties.

Towards the end of "Shambleau," Smith tells his sidekick Yarol what he has experienced:

"I only know that when I felt--when those tentacles closed around my legs--I didn't want to pull loose, I felt sensations that--that--oh, I'm fouled and filthy to the very deepest part of me by that--pleasure--and yet . . . . "

By the way, Martians are the threat in The War of the Worlds and "Shambleau." Bacteria save us in The War of the Worlds. Venerians come to the rescue in "When the Green Star Waned" and again in "Shambleau."

* * *

From all of this, I think we can take a few things about tentacles in fantasy fiction:

First, tentacles seem to have come into fantasy fiction by way of science and the pseudoscience, semi-science, or quasi-science of cryptozoology, then by way of the pseudo-scientific fiction, science fantasy, scientific romances, and finally science fiction of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It seems to me that an interest in tentacles is scientific and progressive, not folkloric or traditional.

Second, H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds, clearly a science fiction story, seems a very likely entry point for tentacles into fantasy fiction of all types, including weird fiction. There are tentacles in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, too, but they are the appendages of an earthly animal, not of a creature or being from the other side. Wells was a prototype of the scientist who becomes an author of science fiction, and when he became an author, he brought tentacles along with him.

Third, tentacles probably represent something that we don't easily apprehend, something strange, alien, otherworldly, terrifying, and dreadful, also, nasty, disgusting, nauseating, inhuman, and monstrous, and of course enfolding, enclosing, and engulfing. Tentacled aliens drink blood or energy or life-force in The War of the Worlds and "Shambleau." They are of course the threat in those two stories, plus in "The Call of Cthulhu." The aliens in "When the Green Star Waned" are not tentacled, but they are alien and a threat nonetheless. Only in "Ooze" is the threat something of this earth, even if it has been altered by Frankensteinian (my new word) science. Although it looks to be tentacled on the cover, Rud's giant amoeba sends out seeking and engulfing pseudopodia instead.

Fourth, tentacles don't stand alone--or creep and crawl alone. They are part of an organism that may also be gelatinous, amorphous, rubbery, pulpy, bloated, blobby, twisting, crawling, writhing, and so on, in short, not like us in any way. Significantly, tentacled creatures very often have radial rather than bilateral symmetry. That alone sets them apart from us and most of our fellow-creatures as something bizarre, alien, and otherworldly (Herman Melville's word from Moby Dick).

If weird fiction is about a crossing over of some kind, then the alienness of the creature with tentacles might be a perfect fit into the genre. Maybe that's why it was on the cover of the first issue of Weird Tales and why it appeared again and again in weird fiction and science fiction.

Original text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Buon compleanno, F.M.E.

Monday, February 20, 2023

Weird Tales, March 1923: Tentacles-Part One

The first cover story in Weird Tales is called "Ooze." It was written by Anthony M. Rud. The monster in the story is a giant amoeba. In Richard R. Epperly's cover drawing, it looks more like an octopus with long, reaching tentacles. I don't know why Epperly drew his monster that way. Maybe he or the editor or publisher thought that people would know at a glance what an octopus is. An amorphous blob of protoplasm isn't so easy to recognize.

There are lots of tentacles in weird fiction. I have read a reference to tentacles as being in fact representative of the genre. Unfortunately, I don't have access to the original source, China Miéville's article "Weird Fiction" in The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Mark Bould, et al. (2009). I can offer two examples of tentacles and tentacled creatures as a subject of weird fiction. One is a critical or analytical work, "'Comrades in Tentacles': H. P. Lovecraft and China Miéville" by Martyn Colebrook in New Critical Essays on H.P. Lovecraft (2013). The other is Mr. Miéville's own novel Kraken, from 2010. In case you didn't know it, things from 2010 are considered new, as in the phrase "the New Weird."

The idea that tentacles are representative of weird fiction may be mostly China Miéville's. There appears to be some theorizing behind it and the theorizing appears to be his. I haven't read Mr. Miéville's writing on the subject, but I believe he's correct in tracing tentacles in fiction to the late nineteenth century. However, my own research leads me to believe that tentacles didn't come from weird fiction so much as from science, pseudoscience--especially cryptozoology--science fiction, and the precursors of science fiction, including pseudo-scientific fiction, science fantasy, and scientific romances.

Cryptozoologists trace the beginning of their field (I won't call it a discipline--it takes discipline to be a discipline) to the late nineteenth century, but the study of unknown animals actually goes back centuries. In order for any pursuit to become a science, though, there first has to be science. Science didn't have a start date, although it seems to have recently developed an expiration date, which was yesterday or the day before. I guess we should just say that science evolved from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. And that's when Pierre Dénys de Montfort (1766-1820) lived, that is, at the end of that period. Montfort studied mollusks, a group of animals that seem almost alien to us, one that includes octopuses, squids, nautiluses, and cuttlefish. You know Montfort's work, even if only by one image, that of the kraken, a legendary creature he believed to be a giant octopus. Montfort's theorizing began after he had read about the discovery of a great tentacle in the mouth of a whale. In other words, Weird Tales began with tentacles and so did cryptozoology. Anyway, Montfort believed in the giant octopus, so much so that he attributed the loss of a British flotilla to the kraken's depredations. He was wrong and died in poverty and shame. In other words, there was a time when people who were wrong about things were punished rather than rewarded. Now it's the other way around.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson immortalized the kraken in his poem of the same name, from 1830:

The Kraken

by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far, far beneath the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides; above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages, and will lie

Battening upon huge sea worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

It's a strange and vivid, a frightening and apocalyptic poem. There is a faint or not so faint awareness of the natural sciences in its lines, most detectable in Tennyson's use of the Greek word polypi. Polypi is plural, of course, and refers to an archaic word for octopus or cuttlefish, polypus, meaning, more or less "many-footed." The French word for octopus is poulpe. Despite the similarity, there is apparently no relationship between the words poulpe and pulp. So, no, pulp fiction is not poulpe fiction and not the literature of octopuses, or of the tentacle. But wouldn't it have been a nice way to draw a circle?

Anyway, it seems clear that the Kraken in Tennyson's poem is a greater creature than the "[u]nnumbered and enormous polypi" that seem to attend it. But we don't have a description: the Kraken remains a mysterious creature, a great natural or perhaps supernatural force. If you detect Cthulhu in Tennyson's versifying, you're probably on to something. Author Robert Price was apparently the first to draw a connection between "The Kraken" and H.P. Lovecraft's story "The Call of Cthulhu" from nigh on a hundred years later. I think the similarities of the latter to the former are unavoidable. Good work, Mr. Price.

(Update, Feb. 22, 2023): In Moby Dick (1851), there is a sighting of but no battle with a giant squid. The author Herman Melville described the creature in Chapter 59, called "Squid":

A vast pulpy mass, furlongs in length and breadth, of a glancing cream-colour, lay floating on the water, innumerable long arms radiating from its centre, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas, as if blindly to clutch at any hapless object within reach. No perceptible face or front did it have; no conceivable token of either sensation or instinct; but undulated there on the billows, an unearthly, formless, chance-like apparition of life.

Note the references to the squid as a "vast pulpy mass" and as "unearthly" and "formless." There will be more descriptions like these in the next part of this series.

There's a battle with an octopus in The Toilers of the Sea by Victor Hugo (1866). Three years later, a giant squid appeared in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne (published 1869-1870). Verne wrote before there was such a named thing as science fiction. His works were something new or almost new in the world, though, and so there had to be some kind of name for stories of their type. In a discussion of literary items published on November 28, 1884 (p. 6), the Boston Evening Transcript referred to "Jules Verne's stories, with their magic machinery of pseudo-science." That's the earliest example I have found of Verne's name coupled with the term "pseudo-science." "[M]agic machinery" refers to what some people might call super-science or superscience, like in the James Bond movies or Marvel Comics. There was also a pulp magazine called Super Science Stories. You can see one of its tentacle covers below.

My purpose isn't to trace the history of the terms "pseudo-science" or "pseudo-scientific," but now that I'm on it, I might as well keep going for a while. And--holy cow!--I found the phrases "weird tale" and "pseudo-scientific stories" in the same article--and it's from 1896, the decade during which pop culture began in America!

The leading story of the Argonaut of July 6 is "The Mines of Mars." It was written by Maria Roberts, who, some time ago, had a very striking story in the Argonaut entitled "The Mystery of Asenath."

The present story is a weird tale of a clairvoyant's two trip [sic] through space to the distant planet that many now suppose to be inhabited, and is one of those pseudo-scientific stories for which the Argonaut has long been celebrated. (Los Gatos Mail, July 7, 1896, p. 5).

(The phrase "pseudoscientific tale" didn't come until later, in the Pittsburgh Daily Post, December 5, 1908, page 5, in regards to Campbell MacCullough's story "The Fourth Dimension.")

Maria Roberts' story, in the San Francisco Argonaut, from January 11, 1892, was actually entitled "The Sorcery of Asenath." It's about Voodoo and it's set in the American South. A brief newspaper review called it "weird and uncanny in the extreme," so there are those two words again. "The Sorcery of Asenath" was reprinted in Argonaut Stories, edited by Jerome Hart and published in 1906. It was also reprinted in the New Orleans Crescent. You will remember that I wrote recently about another story in the Crescent, this one called "A Christmas Reminiscence," from Christmastime, 1868. It was written by a pseudonymous author calling herself Hagar. Her subject was also Voodoo or Voudou.

By the way, no one knows anything about Maria Roberts. She may have been a teacher in California. She is in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database only by name and for her authorship of "The Sorcery of Asenath." We should add "The Mines of Mars: A Weird Tale of a Clairvoyant's Two Trips Through Space" to her credits. That story was in The Argonaut for July 6, 1896. The Argonaut should not be confused with Argosy, the American magazine that ushered in the pulp era in its issue of December 1896. It won't, of course, be confused with the short story "The Chronic Argonauts" (1888) by an author whose name is going to come up really, really soon, like if you were traveling in a time machine to the end of this article.

Proto-science fiction or science fantasy stories were sometimes called "pseudo-scientific." The term "pseudoscience" was and is also used to describe fields of endeavor that make out like they're scientific but really aren't. Phrenology is a good example. The Hollow Earth theory is another. Cryptozoology is kind of split. Looking for, discovering, and describing previously unknown animals is a legitimate scientific endeavor. The okapi, finally described by Europeans in 1901, is kind of the spirit animal of cryptozoologists. On the other side of the coin are people who go out on weekends looking for Bigfoot at the local state park. Cryptozoology as a quasi-scientific, semi-scientific, or pseudoscientific field got its start in 1892--when else?--and the publication of crypto- and just plain zoologist Antoon Cornelis Oudemans' book The Great Sea Serpent, and so we're back to monsters of the sea, except that Oudemans theorized that sea serpents are actually some unknown species of giant seal. So no tentacles.

The point of all this is that tentacles in weird fiction are probably not from folklore, myths, legends, fairy tales, weird tales, or any other old or traditional form but instead from science, pseudoscience, and pseudo-scientific fiction from the nineteenth century. That's what the evidence seems to show. In order to make the leap--or crawl the creep, I guess--into science fiction, tentacles needed treatment from a biologically trained author. Anthony M. Rud, whose parents were medical doctors and who studied to be a doctor, too, was one of them. But he was preceded by another and far more well-known author with a background in biology. His name was H.G. Wells.

To be continued . . .

|

| Pierre Dénys de Montfort's "Le Poulpe Colossal 1801," the Giant Octopus or Kraken of cryptozoology. |

|

| Classics Illustrated #56, illustrating The Toilers of the Sea by Victor Hugo, from February 1949. Cover artist unknown. |

|

| An illustration for Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne, from a 1922 edition, illustrated by Milo Winter (1888-1956). That's a nice picture. |

|

| A record cover for Jonny Quest in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, presented by Hanna-Barbera Records in 1965. Even under water, Race Bannon's hair stays in place. |

|

| Here's a bonus, the cover of Peril, The All Man's Magazine, from October 1956: another first issue, another tentacled creature on the attack. |

Original text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Wednesday, February 15, 2023

Weird Tales, March 1923: Main Title Logo

The first issue of Weird Tales was dated March 1923. What many fans forget is that "The Unique Magazine" had a companion title that had begun in print nearly six months before. It was called Detective Tales, and the first issue had a cover date of October 1, 1922. Edwin Baird was the editor of both magazines, which were published by Rural Publishing Corp., a then-new company started by J.C. Henneberger and John M. Lansinger.

There were five issues of Detective Tales leading up to March 1923. Their numbers and dates:

- Volume 1, Number 1--October 1, 1922

- Volume 1, Number 2--October 16, 1922

- Volume 1, Number 3--November 1, 1922

- Volume 1, Number 4--Nov. 16/Dec. 15, 1922

- Volume 2, Number 1--February 1923

Detective Tales started out in its first issue with eleven stories, plus eight nonfiction pieces, plus two editorial pages. I believe the first four issues (i.e., all of the issues comprising Volume 1) had forty-eight pages each. By February, the magazine had expanded to 192 pages and had begun calling itself "America's Biggest All-Fiction Magazine." The issue of March 1923 was Volume 2, Number 2. It, too, contained 192 pages. There were twenty-two stories in that issue, plus an editor's page called "A Chat with the Chief."*

Richard R. Epperly created the cover illustration for the first issue of Weird Tales. He also created the cover illustration for the March 1923 issue of Detective Tales. These two covers appear below, side by side. As you can see, both covers were printed using a two-color process, and the color scheme on both is the same, orange and black. However, Epperly's illustration for Detective Tales is a line drawing, whereas his illustration for Weird Tales is done in half tones. I'm not sure of the medium, but it looks like watercolor.

The designs are similar. Both have, on the left, a plaque-like design (or cartouche) containing cover blurbs. These were no doubt typeset. Above are the main title logos and subtitles for each of the two magazines. The main title logos appear to have been hand lettered, while the subtitles and other information (date, place of printing, price) were all typeset.

Richard Epperly was a commercial artist. I haven't yet read very much about his career, but I assume he took a course of study in cartooning, illustration, lettering, commercial art, and/or advertising art. His hand-lettered main title logos for Detective Tales and Weird Tales are essentially the same in terms of their design and technique.

I have a book called Speedball Text Book, prepared by Ross F. George. Mine is the 16th edition, which is dated 1952, but I doubt there were many changes from earlier editions. I think the first edition is from the early 1930s, or not long after Epperly created the cover designs you see below. In any case, Epperly's lettering is similar to what George called Round Gothic with an F-B-1 Speedball pen point (p. 13) or Condensed Poster Gothic using an A-1 point (p. 41). Maybe Epperly modeled his lettering after one of these or a similar display face, or maybe he created his own style of lettering based on his art training.

Again, we should probably consider Detective Tales a companion magazine to Weird Tales. That's how I'm going to look at it. As such, it's deserving of study. I'll look into Detective Tales soon. But first, I have more on the first cover and the first issue of Weird Tales.

*Thanks to The FictionMags Index for its list of issues and contents of Detective Tales magazine.

Text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Monday, February 13, 2023

Weird Tales, March 1923: Cover Variants

The first issue of Weird Tales has a cover date of March 1923. The price was twenty-five cents. That was a lot for a pulp magazine, but inside were twenty-six stories, including twenty-two short stories, three novelettes, and the first of a two-part serial, 192 pages in all. The cover art was by Richard R. Epperly, a young commercial artist in Chicago. His was the only illustration in that first issue.

The cover story in the first issue of "The Unique Magazine"--it was called that from the beginning--was "Ooze" by Anthony M. Rud. Epperly's illustration shows the eternal triangle of man, woman, and monster, the man playing his role as hero and rescuer, the woman as damsel in distress, and the monster as monster. Was this the first depiction of a science-fictional monster (versus a folkloric monster) on the cover of an American pulp magazine? I can't say.

The cover of Weird Tales, Volume 1, Number 1, may have been a first of another kind: it was probably the first American magazine with cover variants. That wasn't intentional. Somebody at the printing plant messed things up by switching either the printing plates or the ink so that orange printed in black and vice versa. I'm not sure how many surviving issues there are of Weird Tales #1, but both variants are still in existence. And I can't say how many of each variant were printed. Suffice it to say that Rural Publishing Corp. was almost certainly not in a financial position to destroy the issues printed in error. The cover with the switched colors is a little odd--it looks kind of like a negative image--but it's not a complete disaster. Sometimes you just have to go with what you've got.

The explanation behind the mistake is that the printer switched the printing plates or the colors of ink. That suggests that this was a two-color process rather than a three-color process. The color orange, then, would have been printed from one plate (orange) rather than two (yellow plus red or magenta to make orange). The other plate would have been black of course. A two-color process would have been cheaper than a three- or four-color process but would still have allowed some color on the cover. A black-and-white cover--i.e., a one-color cover--would probably have been bad for sales, even if Weird Tales was the first magazine of its kind and practically guaranteed to find an eager and waiting readership.

That explanation doesn't go all the way, though, for the main title logo is the same in both versions: in both, the lettering is black and the lines above and below are orange. So could the cover have actually been printed twice, first with the logo, then with the illustration (or vice versa)? That doesn't make much sense. If you're trying to keep down costs, you don't send your stuff through the printing press twice. Maybe someone who knows about these things can propose an explanation.

Anyway, the first issue of Weird Tales was also the first issue of an American magazine devoted to fantasy fiction. Maybe (though I doubt it) it had the first science-fictional monster on the cover of an American pulp magazine. And it was possibly or probably the first American magazine with cover variants, even if those were unintentional. There are more firsts on their way and more about the first cover and the first issue of Weird Tales.

Friday, February 10, 2023

Bacharach, Blob, & Brennan

Today I write about a circle. The circle begins with Burt Bacharach, who died two days ago, on February 8, 2023, at age ninety-four. Everyone who grew up in the 1960s through the 1980s remembers his songs. There are so many that are so good and come so quickly to mind that as soon as you hear his name, one of them is bound to start playing in your head.

Burt Bacharach and Mack David collaborated on the theme song for the 1958 film The Blob. If you grew up during the 1950s through the 1970s, you probably saw The Blob either at the theater or on late-night television. Maybe a horror host presented it for your consideration.

The star of The Blob was Steve McQueen, about whom I wrote recently. We think of The Blob as a science-fiction monster movie or an alien invasion movie, but it's also a car movie and a teenager movie (even though Steve McQueen was already twenty-seven when it was released). Teenagers drive around in their cars and save the day in The Blob. The plot is like a cross between the first encounter with Mothman in 1966 and the movie American Graffiti.*

The plot is also like Joseph Payne Brennan's novelette "Slime," from Weird Tales, March 1953. Brennan gets short shrift when it comes to The Blob. You might think that the similarity between the two stories is just a coincidence. Maybe it's a case of convergent evolution. But if you consult the description of the Joseph Payne Brennan Papers at Brown University Library, you will find that there appears to have been legal action involving The Blob and "Slime." The word plagiarism comes up in fact. Unfortunately, we have only a description of the papers available to us on line. It would take a trip to the library, I guess, to find out what it was all about.

Click on the words below for a link:

"Slime" was the cover story for the March 1953 issue of Weird Tales. As it so happens, that was the thirtieth-anniversary issue of "The Unique Magazine," an anniversary that seems to have been observed only in "The Eyrie," in a letter by Irving Glassman of Brooklyn, New York, on page 70. That was the last chance for anyone to observe a nice, round-numbered anniversary issue in the original run of Weird Tales. The magazine came to an end exactly a year and a half later, in September 1954. Virgil Finlay did the cover art for both, March 1953 and September 1954.

Thirty years before "Slime," there appeared another slime-blob-jelly-ooze cover, the first in fact for Weird Tales. This was of course in the first issue of Weird Tales, March 1923. The cover story was "Ooze" by Anthony M. Rud. The monster on the cover looks more like an octopus. If you read the story, you will find that it's actually a giant amoeba. Whereas Rud told his story from the point of view of an after-the-fact human investigator, "Slime" begins with the monster.

And that leads into the next few parts of this series.

*Terrence Steven McQueen (1930-1980) and I share a first name, though his has one more "r" in it. That gave him extra Vrr-oom. He was born in Beech Grove, Indiana, a town that has been swallowed like the Blob by my native city of Indianapolis. James Dean (1931-1955) was also from Indiana. I think Steve McQueen is way cooler. He was also a better driver.

Text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Thursday, February 2, 2023

Weird vs. "The Weird"

When I wrote the first draft of my entry on Weird in Beowulf (Jan. 28, 2023), I used a little different title and a little different expression: I referred to weird as "the weird." I have to admit that I was influenced in that by the expressions in common use now, namely, "the weird" and "the New Weird." After reading and thinking about it more, I decided to remove the "the" and leave it at just "weird."

The definite article may seem like a small thing, but it isn't really. You might have heard that the Associated Press has instructed that we are not to use it when referring to groups of people. I take it that the AP is not like Soylent Green in that it's not made of people. Maybe it has been taken over by an AI, and so it can go on using a word--the Associated Press--that it has forbidden the rest of us from using. (What's the band The The supposed to do? Go nameless?) Maybe it should change its name to the Artificial Intelligence Press, AIP for short. You might have heard, too, that there are AIs in existence or in development that threaten to take over the jobs of journalists. I'm pretty wary of AI, but I have a feeling that it can do a better job at these things than can human journalists. Maybe they can learn to code.

Anyway, the definite article is no small thing, even if it is only three letters long. Here are my thoughts: to call weird or Weird "the weird" is to make it into a definite thing, an object, a category, a theoretical concept, a force, possibly a material force. (One of the leading theorists of "the weird" is a Marxist.) If we call it "the weird," then it seems to me that we have mastered it. We have turned it into something that can be understood, that can be held in the mind, examined and manipulated, turned this way and that. If we call it "the weird," we have turned it into something it is not. I think we have misinterpreted it, for we are not the masters of weird. Weird is not for us to understand. Weird does what it wants with us, not the other way around.

Like I've written, I don't think that weird is a force. I think of it more as a condition, perhaps a condition of our existence in this world. We don't say "the life" or "the love." We say "life" and "love." It's not "the faith" or "the madness" or "the despair" or "the joy" or "the death." You get my meaning. There's another offense in calling it "the weird," too. It seems a pretentious thing, the act of the intellectual too full of himself and his own ideas, too prissy and insistent on establishing and maintaining a name for himself by formalizing and theorizing on a literary genre that may be mostly his own invention, or at least mostly his own discovery. (We shouldn't leave out commercial considerations here, either: even Marxist authors like to sell their books in a free and open marketplace, although they might like it better if their god, the State, could compel people to buy their books.) But weird exists outside of literature. We write about it because it does, and literature is supposed to reflect life. Weird predates writing. An awareness of it does, too. We might call Beowulf and his Geatmen primitive or savage, but they knew a few things we don't. In our post-civilized state, we seem to have lost touch with the world, with nature, including our own nature, and with reality itself. It's no wonder weird was almost lost and that we don't really know what "weird" means anymore.

Weird is not a genre, nor is it a literary theory. It's not an intellectual system. It's not the sum total of the words or the very pulpish prose used to write our way around it. (Sorry, Lovecraft. Sorry, current Weird Tales website.) It's not a body of works. It's not in the names of authors thrown around in any essay, introduction, anthology, or website, even if they are from special places that are not the United States or the United Kingdom. (Namedropping is a favorite habit of another of the theorists of "the weird.") Again, we are not the masters of weird. It acts upon us. We write about it because we have become aware of it and witnessed or experienced its workings. But we may not understand it. In its essence, weird is beyond our ken, another Scottish word by the way.

So these are my thoughts, and they are why I won't reduce weird or Weird by calling it "the weird." It's also not "the New Weird," as something that is more than a decade old can't really be considered new. Anyone who doubts that should go get one of these new gadgets called a smartphone--you may have heard of them--and ask it how old it is.

So, no "the."

No "new."

Just weird.

|

| Grendel, by Lynd Ward. |

Text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley