The weird tale is a form, an old form to be sure. Weird fiction is a literary genre of more recent development, as all fiction is when compared to tales, ballads, legends, and so on. In the twentieth century, there became a kind of theory of weird fiction. H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) seems to have been its chief theorist. I think Farnsworth Wright (1888-1940) played his part as well. Now there are weird fiction studies and weird fiction journals.

There were weird tales--tales of fate--long before they were so named. Originating in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, weird fiction is, again, a more recent development than is the older and more traditional weird tale. Weird fiction as a named or circumscribed genre, eventually with some kind of literary theory behind it, seems to have followed close on the heels of the writing and publication of the stories that make up the genre. In other words, the works came first, then they were thrown together into a named genre. That's how it seems anyway. But how did it all develop? I can't say for sure. All I can do is offer some bits of evidence gleaned from newspapers and literature, i.e., the results of searches I have conducted on line and in one lone book--a children's book called Weird! The Complete Book of Halloween Words by Peter R. Limburg (New York: Bradbury Press, 1989). I can't say that any of the following makes for a first. All I can say is that these are the earliest instances that I have found of the terms weird tales or weird tale, weird fiction, and weird (or the weird) as a noun in newspapers and in literary works, all from the late eighteenth and early to mid to late nineteenth centuries, and all from a time when literature for the masses was on the rise.

Weird Tales & Weird Tale

Earliest Use of Weird Tales in a Newspaper:

From the Manchester Times, March 25, 1843 (p. 4) in a review of The Story-Teller, or Table-Book of Popular Literature, A Collection of Romances, Short Standard Tales, Traditions, and Poetical Legends of All Nations, etc., edited by Robert Bell (London: Cunningham and Mortimer, Publishers, 1843). Specifically, the reference is to "the ballads and weird tales of Germany."

(This may be the same book as: The Story-Teller, Or, Minor Library of Fiction, A Collection of the Choicest Tales, Legends, and Traditions of All Nations, etc., Volume 1, edited by Robert Bell [London, 1833].)

Earliest Use of Weird Tales in a Novel or Romance:

From Cranford (1851-1853; 1853) by Mrs. Gaskell (Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell). From Chapter IV:

The room in which we were expected to sit was a stiffly-furnished, ugly apartment; but that in which we did sit was what Mr Holbrook called the counting-house, where he paid his labourers their weekly wages at a great desk near the door. The rest of the pretty sitting-room--looking into the orchard, and all covered over with dancing tree-shadows--was filled with books. They lay on the ground, they covered the walls, they strewed the table. He was evidently half ashamed and half proud of his extravagance in this respect. They were of all kinds--poetry and wild weird tales prevailing. He evidently chose his books in accordance with his own tastes, not because such and such were classical or established favourites.

(Here is an instance of the frequent association of the words wild and weird.)

Earliest Use of Weird Tale in Prose in an American Newspaper:

In "A Plea for Mendota," correspondent Alice Fay, writing from the shores of Fourth Lake, Wisconsin, recounted a "weird tale," told to her in a vision by the spirit of an American Indian woman, this in a letter to the editor of the Wisconsin State Journal, Madison, Wisconsin, August 21, 1856, page 3.

(Note that fay, meaning "fairy," is from the word fate.)

In a poem called "Sending for God" by Mrs. Brooks in the Weekly Atchison Champion, Atchison, Kansas, November 12, 1859, page 1.

Earliest Use of Weird Tale in the Title of a Novel or Romance:

Bruar Castle: A Weird Tale for a Winter Night by Cecilia M. Blake (C.E. Weldon, 1867).

Other Early Uses in Newspapers of Weird Tales or Weird Tale in Reference to Literary Works or Authors:

- In reference to Samuel Taylor Coleridge; 1840s and '50s.

- In reference to "The Enchanted Hare of the Ardennes" by an anonymous author; in Bentley's Miscellany, CCXLI, 1857.

- In reference to the Scottish poems "Tamlane" and "Kemp Owain"; 1858.

- In reference to Sir Walter Scott, of course a Scottish author; 1858, 1859.

- A newspaper item referring to an unnamed "weird tale of a haunted house," in actuality a reference to "The Haunted and the Haunters; or, The House and the Brain," a novelette by Edward Bulwer-Lytton published in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, DXXVI, August 1859. Note the Scottish place of publication. "The Haunted and the Haunters" was reprinted in Weird Tales in May 1923. It was the first in a series of reprints called "Masterpieces of Weird Fiction."

- In reference to: Sir Rohan's Ghost, A Romance by Harriet Prescott Spofford (1859, 1860). Harriett Prescott Spofford (1835-1921) was an American author. She is in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, in an entry that you can access by clicking here. I don't know when and where the story is set, but Rohan is a Celtic surname, originally from Brittany. The word itself is similar to rowan, another name for mountain-ash. Rowan is a word used in Scotland and northern England. The rowan tree is said to have magical powers.

- Other references, some to real-life tales of death and fate, 1851 and after.

Use of the terms weird tales and weird tale became more common as the nineteenth century went on. In 1885, Scribner and Welford of New York, New York, and John C. Nimmo of London published Weird Tales by E.T.A. Hoffman. Ten years later, the Henry Altemus Company of Philadelphia began publishing various editions of Edgar Allan Poe's Weird Tales. These were popular editions. I suspect they sold well, and it may have been that by the early years of the twentieth century, no one would have puzzled over the meaning or shrunk from buying and reading a collection of weird tales. It seems to me that the negative connotations of weird came later, after the original meaning of the word as "fate" or "destiny" had fallen away. Now weird is thought of in the sense of "that weird guy over there . . . ," and nobody wants to get near him or the word weird.

* * *

Before going any further, I would like to write about Cecilia M. Blake, who has nothing on the Internet in the way of a biography:

Cecilia McKenzie was born in about 1825 in Perthshire, Scotland. She married Thomas Whittet while still quite young. Afterwards she married John Chalmers Blake, with whom she had a daughter, Cecilia Hill Blake, born on March 16, 1855, in Eastwood, Renfrew, Scotland. Cecilia M. Blake was a teacher, school principal, and school proprietor. Annuitant is in reference to her status as the receiver of an annuity, possibly as a widow.

Cecilia M. Blake, also known as Mrs. Blake, was the author of:

- Glenrora: Or The Castle, The Camp, And The Cottage (1864)

- Bruar Castle: A Weird Tale for a Winter Night (1867)

- Cecile Raye: An Autobiography (1868)

- Among the Water Lilies (1895)

- Tephi, An Armenian Romance (The British Girls Library, date unknown)

I don't know the date or place of her death. It's worth noting that she was a native of Perthshire, in which Birnam Wood and Dunsinane Hill, mentioned in Macbeth, are located.

* * *

Weird Fiction, plus Weird (or the Weird) as a Noun

Earliest Use of Weird Fiction in an American Journal or Newspaper:

In reference to a story called "A Christmas Reminiscence" in the New Orleans Crescent newspaper, Christmastime, 1868, as "a strange, weird fiction." The story, by a pseudonymous author calling herself Hagar and originally published in The Crescent Monthly magazine, concerns Voodoo or Voudou. In the story itself, reference is made to "that weird woman Juba."

Other Early Uses in Newspapers of Weird Fiction in Reference to Literary Works or Authors, 1860s through 1880s:

- In reference to The House of Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1851).

- In reference to Zanoni by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1842).

- In reference to Toilers of the Sea by Victor Hugo (1866), specifically in reference to a fight with a giant octopus.

- In "Her Answer" by Robert Burns (1795).

- In "Hic Jacet Robin Maroun" by R.H.A., a poem in remembrance of the poet, in the Chester Chronicle, Chester, England, September 28, 1810, page 4:

"hear Robin's weird, wi' trickling tear--

He's sunk to ruin."

A glossary to go with the poem defines weird as "fate."

- Peter R. Limburg's book led me to a search of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats. I found six instances of weird in Shelley's complete verse, including in his long poem "Alastor, or The Spirit of Solitude" (1815, 1816). In every instance, weird is used as an adjective, including in this striking line from Canto 9 of "The Revolt of Islam" (1818): "Some said, I was a fiend from my weird cave." I also found weird in Keats' poem "Lamia" (1820), where it is also used as an adjective.

- "The Weird of the Douglas, A Metrical Tale" in Taits Edinburgh Magazine, No. 49, January 1838. Scottish surname, Scottish place name.

Some Uses of Weird (as in the Weird) as a Noun in a Novel or Romance:

- The Weird Sisters, a Novel by William Lane (1794).

- In Bannockburn, A Novel by John Warren (1821), a character called "the weird woman" speaks:

"Carry the corpse away!" said a hollow voice, "and cry the coronach! The weird is run--the raven croaks--the black banner flies! Oh, happy, happy hour! Vengeance! vengeance! Hour of vengeance! I hail ye--fa' whare ye may!"

Does the weird woman address Fate--"fa'"--when she cries, "I hail ye--fa' whare ye may!"?

- The Weird Woman of the Wraagh, or, Burton and le Moore by Henry Coates (1830).

- From Ralph Wilton's Weird by Mrs. Alexander (Annie French Hector, an Irish/British author, 1871):

"Ah ha, lad!" said Moncrief, in his unmistakable Scotch tones, "you must just 'dree your weird.'"

The meaning of this traditional Scottish expression is to accept and surrender to one's fate.

- Wyllard's Weird, a Novel by Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1885).

The concept of weird fiction as a type, category, or recognizable literary genre seems to have developed in the 1870s or 1880s, certainly by the end of the 1880s. For example:

"Nothing in real life has equalled these Whitechapel murders, the only approach to them is to be found in the weird fiction of Edgar Allan Poe." From "The Whitechapel Murders" in the Spokane Morning Review, October 3, 1888, page 2.

and:

"We have received from the publishers [Vizetelly & Co.] the latest additions to this library of weird fiction--The Golden Tress and Thieving Fingers." (By Fortuné du Boisgobey.) From the Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle, April 9, 1887, page 9.

So, weird fiction as a category or genre predated science fiction by four decades or more. And of course the first weird fiction magazine, Weird Tales, came before the first science fiction magazine.

* * *

You must have noticed by now three patterns in the use of the expressions weird tales, weird tale, weird fiction, and weird or the weird as a noun:

First, there is without a doubt a connection of weird and the weird to Scotland. That is to be expected, as weird is a word that fell out of use in English but persisted in the Scots tongue, most likely, it seems to me, because it persisted in the Scottish psyche or worldview. Weird returned to English, first by way of Shakespeare's Scottish Play, afterwards--though not exclusively--by its use by Scottish authors or in reference to Scottish authors and their works. The Irish may have saved civilization, but the Scottish saved weird.

Second, and perhaps with some real significance, women authors--Mrs. Gaskell (1851-1853), Alice Fay (1856), Mrs. Brooks (1859), Cecilia M. Blake (1867), the pseudonymous Hagar (1868), Mrs. Alexander (1871), Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1885)--were early users of these expressions in print. That makes me wonder: Is there something in the female psyche or the female experience that is more open to the idea that weird, or fate, is active in human affairs? Or is there a simpler explanation, for Alice Fay and Mrs. Brooks at least, namely, that they picked up on the term weird tale by reading Cranford? As for Mrs. Blake, she was a native Scotswoman born in the country of Macbeth and of the original Weird Sisters. Maybe weird never left her consciousness, just as it never left that of her countrywomen and countrymen, as it did in the rest of the English-speaking world. As for Mary Elizabeth Braddon, her novel is set in Cornwall, another of the Celtic regions of the British Isles and the European Continent. In any case, weird was saved and we have it today.

Third, related to the second, there is more than one "weird woman" in the works I have catalogued here. These may be descended from Shakespeare's Weird Sisters. More likely, the Weird Sisters are descended from an older type, personified in the Fates but also in the more common and familiar type of soothsayer or fortuneteller. The weird woman goes beyond the soothsayer or fortuneteller, though. She seems to be a type that has been lost. We should bring her back. There is a movie called Weird Woman, by the way. Based on the story "Conjure Wife" by Fritz Leiber, Jr. (Unknown Worlds, Apr. 1943), it was released in 1944 as a part of the Inner Sanctum series of movies.

To be continued . . .

|

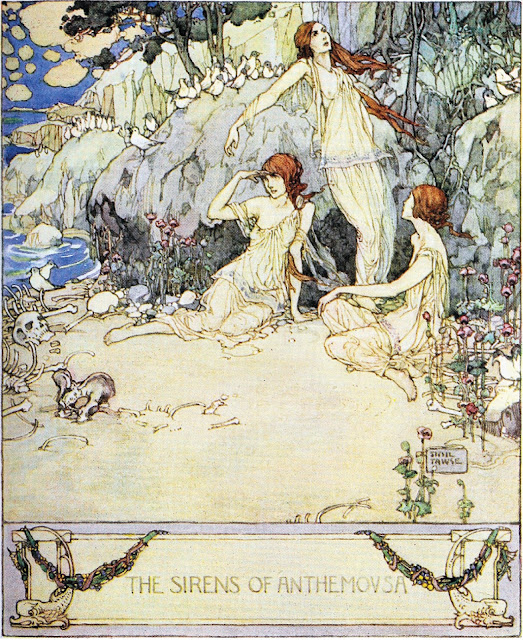

| English artist Sybil Tawse (1886-1971) illustrated a later edition of Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell. Those illustrations led me to this one, entitled "The Sirens of Anthemovsa." Once again, the women are in threes. They are reminiscent of the Fates. Sybil Tawse is not in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database. That seems like an oversight that should be corrected. I had not heard of her before finding her illustrations on line in my preparation of this series. An Irish blogger and artist named Dara Theodora featured her on her Wordpress blog on June 20, 2018. You can see what she posted by clicking here. |

|

| Universal Pictures released Weird Woman in 1944. I haven't seen this movie, but descriptions indicate that the title character is considered a witch. That may be based on an interpretation of Shakespeare's Weird Sisters as witches. In doing the research for this article, however, I have found that the original "weird woman" seems not to be a witch at all. Instead, she seems to be a teller of the weird, or fate, of a given person or persons. The word weird was once almost lost. Now it seems the original meaning of the word has been lost instead. And because of that, the weird woman as a type has been lost. Like I said, we should bring her back. First, though, we need to understand the original Anglo-Saxon or Celtic or Scottish concept of weird or the weird. If we can reach that kind of understanding, then maybe we can bring back the weird woman, not as a stock character or stereotype but as a fuller character. Before that can happen, I guess, we have to back away from our current worship of materialism, atheism, and Scientism. We also have to learn once again to respect women. And before we can do that, we have to acknowledge that there is only one, inviolable definition of woman, only one category woman--and you don't have to be a biologist to know what they are. All of that seems like a pretty tall order at this late date. In thinking and writing about all of this, I am reminded that Weird Tales had an especial appeal to women--authors, poets, artists, readers, and fans. Editor Dorothy McIlwraith served longer than anyone but Farnsworth Wright as editor of the magazine. That seems fitting. Maybe the unseen host of Weird Tales should have been a woman all along. As for Dorothy McIlwraith: she worked in the United States and was born and educated in Canada, but her family was originally from Scotland. Her associate editor Lamont Buchanan was also from a Scottish family. They, the Buchanans, had at least one weird tale in their Scottish past. |

Original text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley

I'm impressed with your deep research on this topic. Thanks for posting the results of what must have been exhaustive work.

ReplyDeleteHi, John,

DeleteFor some reason, Blogger considered your comment to be spam. I have put it back where it belongs.

Thank you for your comment. It was some work to be sure, not exhausting exactly, and also not exhaustive. But in doing this research, I learned more about the origins of "weird" and the evolution of weird fiction. Now I have what I think is a deeper understanding of both. I would recommend that all readers, writers, and fans of weird fiction look into these things themselves and give careful thought to the whole matter. Maybe then we can have some better and more authentic weird fiction.

Thanks as always for writing.

TH