Author, Journalist, Editor, Traveler, Explorer

Born October 5, 1886, Batesville, Arkansas

Died February 18, 1939, Chicago, Illinois

Merlin Moore Taylor was born on October 5, 1886, in Batesville, Arkansas. His father, Reverend James Jackson Taylor (1855-1924), was a missionary and a member of the Southern Baptist Convention. Reverend Taylor went back and forth between the United States and Brazil during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Merlin Moore Taylor lived in Brazil from 1890 to 1897 and again from April 1899 to August 1900. He was in Rio de Janeiro in 1893 during the Brazilian Naval Revolts, or Revoltas da Armada, in which the city was bombarded by naval forces in revolt against the government. Although he was only a child, Taylor's career as a traveler in foreign lands and a witness to events in faraway places had begun.

Taylor was born and educated in Arkansas, yet he had close connections to his neighboring state to the north. Macon, Missouri, claimed him, and he served with Company D of the 4th Missouri Infantry, enlisting in July 1908 and serving, I believe, three years in all. His wife was Lily May Freeman Taylor (1886-1947). They lived in St. Joseph, Missouri, from about 1902 until at least 1910. Taylor was on the editorial staff of the St. Joseph Gazette during those years. He also worked as a newspaper editor in St. Louis.

By June 1917, when he filled out his draft card, Taylor was in Chicago and working as an editor for William D. Boyce (1858-1929). Boyce was an editor, publisher, explorer, and founder of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) and the Lone Scouts of America. From his headquarters in Chicago, he issued a popular weekly newspaper called the Saturday Blade. After breaking with the BSA, he launched the Lone Scouts of America and began publishing a weekly, eventually monthly, magazine called Lone Scout. Merlin Moore Taylor was editor of both publications. Ralph Allen Lang (1906-1987), thirty years his junior, was a Lone Scout in his rural Pennsylvania home. He also contributed to Weird Tales, though a decade after Taylor. The Lone Scouts were geared towards literary and artistic endeavors. They had their national publication in Lone Scout, but they also produced local journals. In reading about them, I get the impression they were like the fanzines of a later time. I would not be surprised to find that other Lone Scouts contributed to Weird Tales.

In November 1920, while living in Chicago, Taylor applied for a U.S. passport. His intention was to leave from Vancouver, British Columbia, on December 15, on board the Makura, bound for Australia and New Zealand. His expressed purpose was to "travel and obtain data for articles." In 1921, accompanying British magistrate and patrol officer Richard Humphries and with Harry L. Downing of Sydney, Australia, also in tow, Taylor went into the interior of Papua New Guinea. According to Taylor, it was the first time that white men had made that journey in the forty years that it had been a British territory. (1)

Taylor arrived back in Victoria, British Columbia, in September 1921. His experiences and observations while in Papua New Guinea were the basis for his book The Heart of Black Papua, published in 1926. Excerpts from the book were syndicated in American newspapers during the 1920s and '30s. "Two Sorcerers of Black Papua," reprinted in Horror in Paradise: Grim and Uncanny Tales from Hawaii and the South Seas (1986), was also drawn from The Heart of Black Papua. The editors of that book were A. Grove Day and Bacil F. Kirtley.

Merlin Moore Taylor traveled extensively in the United States, South America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, the East Indies, and the South Seas. He wrote travel articles and true crime articles published in a number of newspapers. Living in Chicago in 1930 with his wife, Taylor worked for Chicago Herald Examiner Publishing. He was also a journalist with I.N.S., or International News Service. Fans of 1970s television will remember that Carl Kolchak, the Night Stalker, also worked for the INS, also of Chicago. His employer, though, was the Independent News Service.

Merlin Moore Taylor was a very prolific author of stories and articles published from June 1919 to February 1940. These appeared in Adventure, All-Story Weekly, Asia, The Black Mask, Detective Story Magazine, Novelets, Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, Short Stories, Sport Story Magazine, Star Novels, The Wide World Magazine, and other titles. Although they are not listed in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, some of Taylor's stories have titles that suggest they are genre stories, including "In the Clutches of the Werewolf" (The Regent Magazine #11, Oct. 1924), "The Wolf Man" (Novelets, Jan. 1925), and "The Werwolf’s Claws" (Adventure Trails, Jan. 1929). Taylor had only one story in Weird Tales, "The Place of Madness" (Mar. 1923), and one in Detective Tales, "First Catch Your Rabbit" (Feb. 1923). He also had one story in Amazing Tales, "The White Gold Pirate," from April 1927. Finally, I have found two stories by Taylor syndicated in American newspapers, "By Law of Tooth and Talon," a serial in the St. Louis Star, from 1921, and "The Wicked Flee" in the Chicago Tribune, from December 17, 1922.

According to Lucien W. Emerson in his newspaper history of the Lone Scouts of America (see below), Merlin Moore Taylor died of the effects of blackwater fever contracted when he was in Papua New Guinea. That sad event took place on February 18, 1939, in Chicago, Illinois. Taylor was just fifty-two years old.

Note

(1) Benjamin Stevens Boyce, son of William D. Boyce, also traveled to New Guinea. The younger Boyce died in 1928. His father published posthumously his Dear Dad Letters from New Guinea, dispatched from an expedition to that island country. I don't know if there was any connection between Boyce's and Taylor's expeditions.

Merlin Moore Taylor's Stories in Weird Tales and Detective Tales

Weird Tales

- "The Place of Madness" (Mar. 1923)

Detective Tales

- "First Catch Your Rabbit" (Feb. 1923)

Further Reading- "Murder Plot and Deadly Hate of Sorcerer Make Journey Perilous" by Merlin Moore Taylor in the Washington, D.C., Sunday Star, November 28, 1926, part 5, page 2.

- "The Golden Years of Lone Scouts" by Lucien W. Emerson in Southern Utah News, August 13, 1959, page 1+.

Merlin Moore Taylor's Story:

Like "The Ghost Guard" by Bryan Irvine, "The Place of Madness" is set in a prison, afterwards in a hospital. There is more to Merlin Moore Taylor's story than to Irvine's however, and the twist at the end, though foreseeable, is more powerful.

God earns mention again in "The Place of Madness." Dr. Blalock, who has gone through the ordeal of solitary confinement in a darkened prison cell, speaks from his hospital bed:

And in my agony and fear I cursed the God who had created me and saddled me with this thing [i.e., his conscience]. I learned my lesson, though, before I was through. I who had presumed to place my own puny will above the Great Eternal Will; I who had dared to believe that the great order of things, the plan by which we all must live and die, must make an exception of me, learned that I was wrong.

There are those among us who would place themselves above God, thereby also above nature, reality, and their fellow human beings. I don't sense any prickings of conscience among them, though, and so we have one example of a difference in the moral universe of one hundred years ago versus the apparent utter lack of a moral sense today, especially among our elites.

Taylor wrote of "the Great Eternal Will." Our current problem may also have to do with will. Aleister Crowley infamously wrote, "Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law," while Nietzsche's idea seems to have been that, now that God is out of the way, the will to power remains as a guiding force, or the guiding force, in the lives of men. He also made a connection between the will to power and the desire for cruelty directed at other men. George Lucas got in on the act, too. From Wookiepedia, first a quote, then the beginning of an encyclopedia entry on the Whills:

"The midi-chlorians are the ones that communicate with the Whills. The Whills, in a general sense, they are the Force."

--George Lucas

Star Wars creator George Lucas intended the Whills to be microscopic single-celled life-forms who were essentially God; the will of the Force.

Remember what O'Brien in Nineteen Eighty-Four said about power: "The object of power is power." Power is both the goal and the means of attaining the goal. Power is, among other things, the power to humiliate and the power to inflict cruelty upon our fellow human beings, without guilt, remorse, shame, or fear of punishment. In "The Place of Madness," Dr. Blalock speaks against this kind of worldview. But he still has a conscience. Our current elites, especially in government, are driven by will and a lust for power. They seek to humiliate us, to punish us, to visit cruelty, poverty, and misery upon us. And they seem to take pleasure in all of that and in all of it to be free of guilt. I suppose one day they will have to confront themselves, and if not that, they will at least be confronted by a greater power that in this life they have denied. On the other hand, I feel certain that many of them will go to their graves believing that they remain God-like in all of their qualities. I remember seeing a firefly caught in a spider's web. It went on blinking and blinking, signaling life and promising life even as the end came near. Our elites are not so innocent as that firefly, and yet they go on announcing themselves, even as the end nears. Remember, finally, that Taylor's father was a minister, and that in 1923, humanity was still living near the beginning rather than at the end of a century of horrors.

"The Place of Madness" also recalls Orville R. Emerson's story "The Grave." The theme is much the same, namely of madness brought on by solitary confinement, of a man alone, trapped deep in the earth. Emerson's German soldier is free of guilt however. Dr. Blalock, on the other hand, loses his mind partly because, for two hours, he is utterly alone with himself, his thoughts, and his nagging conscience. The implication in Taylor's story is that an innocent man with a clear conscience can tolerate isolation and sensory deprivation better than can a man wracked with guilt, for a man alone must confront himself.

"The Place of Madness" is unusual in that it's not very sentimental. There are also taboo subjects, including female promiscuity and pregnancy outside of marriage. Taylor would probably have had a hard time placing his story in a mainstream magazine. However, there aren't any weird elements--no fantasy, no horror, and no pseudo-science or science fiction. There is crime, though, and confessions of crime. Maybe "The Place of Madness" could have gone into a crime/detective/mystery magazine. You could call this a conte cruel except that the man who receives punishment is not innocent, and his punishment is not arbitrary. You could also look at Dr. Blalock's volunteering to go into the isolation cell as the workings of the imp of the perverse, or a subconscious desire to punish himself or to visit justice upon himself. There are faint echoes of Poe and Hawthorne, especially The Scarlet Letter, in "The Place of Madness." There may also be Freudian concepts at work.

One last thing: there is in Taylor's story a powerful appeal against solitary confinement in prisons. And what he wrote a century ago is still true today. Solitary confinement remains a question of morality and of humane treatment of our fellow human beings, even if they have committed the most horrendous of crimes. One thing seems certain, and that is that a man alone and deprived of stimuli will lose his mind.

|

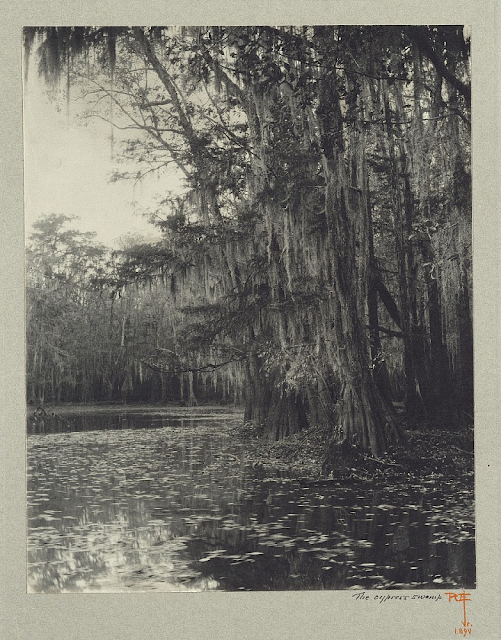

| An illustration from Merlin Moore Taylor's article "Murder Plot and Deadly Hate of Sorcerer Make Journey Perilous" in the Washington, D.C., Sunday Star, November 28, 1926, part 5, page 2. The illustrator was Douglas Ryan. One of the white men in this picture is the author Taylor. I doubt whether Ryan's depiction of him is an actual likeness. |

Text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley