Burroughs & Haggard

Edgar Rice Burroughs was born in Chicago on September 1, 1875, into an old and well-connected family in America. His father was a businessman and during the Civil War a brevet major in the Union Army. Burroughs the younger was related to at least seven signers of the Declaration of Independence, including John Adams. His two greatest literary creations, Lord Greystoke, better known as Tarzan of the Apes, and Captain John Carter, Warlord of Mars, were aristocrats of an old English or Southern type. If in reading all of this and more you were to conclude that Burroughs and his family were conservative, you would be right. His conservatism will come into play a little later in this series.

Although he grew up to be a man of action--he was actually beforehand a boy of action--Burroughs liked to read in his youth, and he possessed a vivid imagination. In that way and probably many others, he differed from his father. "My father was always very stern and military in our relationship," he wrote. "He used to tell me with increasing frequentness--until I was thirty-six--that I would always be a failure, and until I was thirty-six he was right." (1)

I'm not sure that there is a comprehensive record of what Burroughs read as a child or young man. We know that he read Roman mythology as well as The Jungle Books of Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), for he admitted to being inspired or influenced--at least at some level--by those two sources in his creation of Tarzan. It's less certain that he read the works of H. Rider Haggard (1856-1925). I wonder, though, how could he not have? Haggard was one of the most popular and widely read authors of the nineteenth century. His novel She: A History of Adventure (1887) impressed, even astonished, reviewers and critics. It has never gone out of print and has sold in excess of 83 million copies since its initial publication. So did Edgar Rice Burroughs, creator of Lost Worlds on both Earth and Mars, read H. Rider Haggard, the great popularizer of that genre, or not?

In his biography The Big Swingers (1967), Robert W. Fenton made a case based on circumstantial evidence that Burroughs was indeed influenced by Haggard, particularly by She. (p. 62n) Haggard was a source of inspiration for Kipling. We know that much, for Kipling acknowledged in his autobiography, Something of Myself (1937), that he had read and remembered Haggard's Nada the Lily (1892) before beginning his own Jungle Books (1894). So, first came Nada the Lily, then The Jungle Books, and finally, maybe, the creation of Tarzan. But is that a direct and irrefutable line of descent?

Robert W. Fenton made his case, but he wasn't the only one. Richard A. Lupoff did it, too, in Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure (revised edition, 1968). The late Mr. Lupoff even included a family tree showing some of Tarzan's possible ancestors, and these include Nada the Lily. He went further in his speculations, though, in the process making another strong circumstantial case that Burroughs was influenced by Haggard. Both Fenton and Lupoff drew parallels between Haggard's She and two of Burroughs' Tarzan adventures, The Return of Tarzan (1913) and Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar (1916, 1918). (2) But neither was able to pull off a Perry Mason-like revelation in the courtroom of his own well-researched pages.

In 1975, Irwin Porges published a hefty tome called Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Man Who Created Tarzan. (3) His book is heavy on primary sources. In the preface is a photograph of Porges in a Raiders of the Lost Ark-like warehouse in Tarzana, packed to the ceiling with file boxes from Burroughs' long life and career. So you read for a while and then there it is, on page 130: in a letter to The Bristol Times (of Bristol, England), dated February 13, 1931, Burroughs wrote: "To Mr. Kipling as to Mr. Haggard I owe a debt of gratitude for having stimulated my youthful imagination and this I gladly acknowledge," adding, "but Mr. Wells I have never read and consequently his stories of Mars could not have influenced me in any way."

Interesting. My two-fold thesis is holding up. On one side are Utopia, Lost Worlds fantasy, H. Rider Haggard, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. On the other are Dystopia, science fiction, H.G. Wells, and myriad writers who came after him, including, perhaps, H.P. Lovecraft. The parts that don't seem to fit yet are also twofold: Utopia as an expression of a conservative worldview, and, conversely, Dystopia as an expression of progressivism. I might have those parts figured out, though, so stay tuned.

Anyway, there's one more thing to consider in regards to Burroughs and Haggard. She: A History of Adventure was published in book form in the United States in 1887, I think in June. (4) That summer, She was serialized in American newspapers. Towards the end of summer, on September 1, 1887, Edgar Rice Burroughs turned twelve years old. We think of twelve as the the Golden Age of Science Fiction, but before it was that, it must have been a Golden Age of Adventure, too. We can imagine a young Burroughs reading She, perhaps as he lay abed at night, thrilling at the adventure and romance of it and dreaming that he might have such adventures, too--that he might even one day himself become a writer.

To be continued . . .

Notes

(1) Quoted in The Big Swingers: A Biography by Robert W. Fenton (1967), p. 11.

(2) See Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure by Richard A. Lupoff (New York: Ace Books, revised edition, 1968), pp. 225-229, 300-301.

(3) For more on Irwin Porges and his family, see my article "Who Was Arthur Pendragon?" from January 25, 2019, here.

(4) On May 28, 1887, the Chicago Tribune announced the publication of She for the following month. Burroughs was still living in Chicago at the time, with his parents. On July 3, 1890, when he was fourteen, his father shipped him off to his brothers' ranch in Idaho so that he might avoid getting caught up in an epidemic.

|

| Here and below are a few illustrations of H. Rider Haggard's She that you might not have seen before. First, the cover of a British edition published by Hodder. I don't know the year or the artist. (Note the similarity between this cover and the cover of Les Baxter's movie-score album for Barbarian, here.) |

|

| Here's a comic book version from 1950 with cover art by Henry Carl Kiefer (1890-1957). |

|

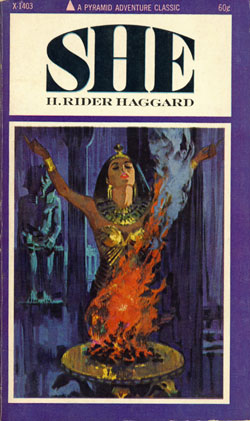

| This is the cover for the Pyramid paperback edition of 1966. The Internet Speculative Fiction Database doesn't give an artist's name, but it kind of looks like the work of Bob Abbett (1926-2015). |

Original text and captions copyright 2021, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Years ago Ace reprinted a book "Gulliver of Mars" complete with a great Frank Frazetta cover. It was written by Edwin Arnold and was originally titled Lieut. Gulliver Jones: His Vacation. The introduction by Richard Lupoff introduced the theory that Burroughs got his Barsoom from the Mars portrayed in this book and that John Carter came from another Arnold book "Phra the Phoenician" I enjoyed Gulliver of Mars enough to read it several times (!) but never did read Phra.

ReplyDeleteHi, Drizzz,

DeleteI looked at my copy of the Ace edition of Gulliver of Mars and read Richard A. Lupoff's introduction. In closing he wrote: "Phra the Phoenician is John Carter!" But that was his closing. He didn't go any farther.

Now, nearly sixty years later, we can read "Phra the Phoenician" on line. Here is a link to Hathi Trust Digital Library:

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000244528

I haven't read this book, but in comparison to "A Princess of Mars": 1) Both begin with an introduction by the author; and 2) Both Phra and John Carter begin their stories by telling that they are old beyond the lifespan of normal men. I have a feeling that more similarities follow.

Two names from Edwin Arnold's work may lead to other characters from fantastic fiction: 1) Pha, Thun'da's girlfriend in the comic book series written by Gardner Fox and drawn by Frank Frazetta; and 2) Gully Foyle, the protagonist of Alfred Bester's incomparable "The Stars My Destination."

Thanks for writing.

TH

Speaking of ERB as a conservative, one to the "Moon" books seems to be very anti-communist. It has been a while since I read them, so I forgot which one it was. The people in charge would take all the goods to evenly redistribute to every one. As usual, they kept most for themselves and everyone else was poor.

ReplyDeleteHi, Iberdot,

DeleteI have another pertinent quote from "A Princess of Mars" that I'm planning to use in this series. I have never read the "Moon" books, so I can't say anything about them. It's interesting that these books include a communist-type society, though. In his book on H.G. Wells, Jack Williamson pointed out the dystopian nature of lunar society in "The First Men in the Moon." Maybe ERB found inspiration there, too, as he seems to have found in other works.

Thanks for writing.

TH

This is off topic but I just stumbled on old copies of the "Fantasy Fan" fanzine from the 1930's on the Project Gutenberg site. Some of them were posted as far back as 2014 so this may be old hat to you.

ReplyDeleteHere's the link: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/subject/27005

ReplyDeleteHi, Drizz,

DeleteNo, I have never seen them before. Thanks for bringing them to my attention.

TH