Beowulf was composed in pre-Christian times but written down only after Christianity had moved into northern Europe. The result is syncretic, that is, a cross between pre-Christian and Christian beliefs. Syncretism was and is a very successful strategy in the growth and spread of Christianity. Rather than wipe out beliefs that came before it, the Church absorbed and modified them. It's why we celebrate Christmas at midwinter.

In his last words, Beowulf mentions both Weird (Wyrd) and "the Creator." The implication is that Weird works on earth, perhaps independently of the Creator. Or is she one of his agents or angels? I can't say. Beowulf seems to have lived and died in an in-between time. But what if the inclusion of Weird in Beowulf is not fully syncretic? What if Weird and God lived side by side for some time in Europe before Weird became what people now call "God's will" or "God's plan for the world"? What if only later did God subsume Weird?

For nigh on a thousand years after Beowulf, Weird was the workings of God--"God moves in mysterious ways" is the saying--and there was a syncretism, with God on top and Weird hidden away. Weird, or Fate, and her seeming random and often cruel ways retreated behind God's will, God's plan, God's mercy, God's love. God took her place; he is loving and caring, even if mysterious. He does things for his own reasons, which may be inscrutable and incomprehensible to us in our smallness, yet are ultimately wise and unassailable. Maybe the weird fiction of the nineteenth century and after chronicles a renewed schism of Weird from God, significantly beginning with the Romantic Period and the rise of the natural sciences.

We think of the Romantic Period as a reaction to the Age of Reason. But there was no simple conservatism in Romanticism. In fact, it may be seen as a search for a third way, for a middle ground between a cleaving to tradition and a radical overthrow of the past. So maybe Weird came back only after we had begun the process of dethroning God, which seems to have been part of the program of Western thought during the nineteenth century. Then, in 1883, Nietzsche wrote that God is dead. A couple of years later, publishers began putting out books with the word weird in their titles. These were no doubt the inspiration for the title, themes, and subject matter of the later magazine Weird Tales, which began one hundred years ago this spring.

So maybe the authors of weird fiction from the 1880s to the 1920s and '30s were simply returning to the Weird of the past. Except that Weird was now embodied or manifested in dark, malign, and alien beings, entities, and forces. Weird may be cruel. She may seem arbitrary. She carries us away. But more than anything, she may actually be indifferent to what we want for ourselves on this earth. Her ways may just be matters of course. These things must be done for no reason we may know. Cthulhu, on the other hand, wishes to crush us and rule over us. He has his designs upon us. He has come into this world to stay. He is bodily, though also in control of nonmaterial forces. But I sense in him an indifference, a malign indifference to be sure, but an indifference nonetheless. In the eyes of Cthulhu, we are nothing. Beyond that, in the greater Lovecraftian universe, we as human beings are insignificant, mere specks. I don't think Weird sees us that way. Weird may carry us away, but we are not nothing to her.

Based as it is on genuine human experience in a seemingly harsh, often cruel, and largely unforgiving world, the pre-Christian concept of Weird is actually profound in its grasp of our condition. It is not the simple or savage or barbaric belief of a pre-civilized people. It may actually be a kind of stoicism, a well-developed philosophy from ancient, civilized, and pre-Christian Greece and Rome. But I sense more in the concept of Weird than simply a kind of stoicism. Weird is at work in the world. No one knows her workings. Whereas Fate may be seen as acting out some kind of moral judgment or dealing some kind of punishment against transgression, Weird is or may be simply neutral. And because of that, we have acceptance. There can be no bitterness or lashing out at her. Our fists would simply fly through thin air. We are urged not to tempt Fate. But Weird is not tempted. Nor can she be avoided. She has her way no matter what we do. As Beowulf says, "Goes Weird as she must go!"

Weird is not a force. I feel certain of that. Weird is embodied in the person of an unseen and unknowable woman or goddess. And yet there is no discrete body or physical manifestation of her. And she is not a she but something else. Weird is at work everywhere at once. Weird is also not necessarily supernatural. Again, Weird may be simply part of our existence. She is in the way we live and ultimately die.

Weird fiction involves things that are weird, uncanny, eerie--all Scottish words--also, strange, fantastic, and possibly, though not necessarily, supernatural. I'll tell you the truth: I don't know what weird fiction is. But I think I know a couple of things that it is not:

First, weird fiction is not science fiction. If there are elements of weirdness in a scientific story (or pseudoscientific story, a term that predated science fiction), then it might best be described as science fantasy rather than as science fiction. To illustrate, I think it more accurate to say that H.P. Lovecraft and C.L. Moore composed stories of science fantasy rather than of science fiction. Both wrote in the weird-fiction tradition, which seems to have come from the Old World as far back as what Jack Williamson referred to as the Hebraic-Egyptian tradition. Edgar Rice Burroughs also wrote science fantasy. Although he was not a science fiction author proper, his stories may be seen as a kind of proto-science fiction. I don't think his stories are essentially weird, though, nor do they contain very many--if any--truly weird elements. I don't think Burroughs had that kind of imagination. Likewise, John Carter is not a weird-fictional hero. He is more nearly a science-fictional hero and a proximate forerunner to the Superior Man-type hero of the 1930s and after. Lovecraft's heroes, if you can call them that, and C.L. Moore's Northwest Smith in particular are clearly not science-fictional heroes in that they are not triumphant. They are in fact weak and in the end often defeated. The difference may come from differences in personality and biography. Remember that Burroughs was a man of action and vigor, whereas Lovecraft and Moore were sickly, at least in their formative years. Anyway, science fiction can have its weird elements, but, ultimately, if it's science-based rather than weird-based, then I think it has to remain within the realm of science fiction.

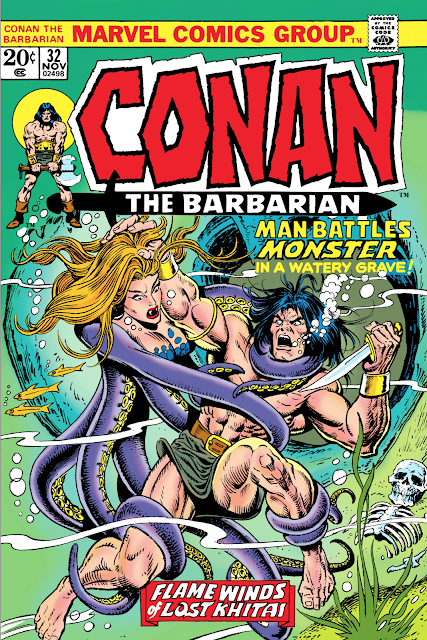

Likewise, weird fiction is not fantasy, or at least it's not high fantasy. The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings Trilogy may have their weird elements, but they are fantasy. Like Robert E. Howard's stories of Conan, they also have elements of heroic fantasy. It seems to me, though, that the Conan stories lie within the realm of weird fiction because of their pervasive weird atmosphere. And let's remember that Howard saw himself as a Celt. Glenn Lord in fact assembled a book about him called The Last Celt: A Bio-Bibliography of Robert Ervin Howard (1976). We should also note that Conan is a Celtic name, and there are similarities between Conan and his countrymen with pre-Christian Celtic cultures and society. Although Weird is in Beowulf, she survived in the real-world realms of Celt-ism. Maybe that's another syncretism: Celts adapted Weird from Beowulf and his pre-Christian culture into their own and there it survived, only to be rediscovered in the nineteenth century, perhaps when it was needed again, perhaps when the Christian-pre-Christian syncretism began to break down and Weird was once again loosed from God.

I have written more than once that weird fiction involves Fate or Destiny as a limiting, corrective, or punitive force--maybe not force so much as outcome. We are permitted only certain things and no more. If we attempt more, we are put back in our place. The Greek notions of hubris and agon may come into play here. When we began our weird fiction book club several years ago, the leader of our group, my friend Nathaniel Wallace, asked us what we think makes weird fiction. My answer was and is that weird fiction involves a crossing over: either we cross over into other realms, or they cross over into or touch ours. Usually, there is a return or a retreat, but there need not be. The crossing over is the key. This, too, can be neutral: moral dimensions may be removed from weird fiction and it can still go about its business.

In reading about weird fiction, I have encountered two or three or four ideas again and again. One is that weird fiction crosses genres. I think that's true, but I think it has been true since the beginning. The claim of "the New Weird" to genre-crossing may very well be inconsequential. It's like inventing a new genre called "the New Western" and then setting all of its stories in the American West. Genre-crossing may very well be built into the definition of weird fiction. There's no need to keep commenting on it. And can we quit calling it "the New Weird"? If a thing is near two decades old, it ain't new anymore.

Second is that weird fiction subverts our expectations, or, as Wikipedia puts it, it "radically reinterprets" its subject matter. Again, I'll label that idea as puerile or sophomoric. Only the childish imagination--including the Marxist imagination--that exists within supposed adults believes in subversion or subversiveness, or in the idea that anything at this late date can be truly radical. What we should all know by now is that everything has already been tried. There is nothing new under the sun. The only reason that all of these things that have been tried don't still exist is that we found out they don't work and discarded them. It is the things that have been tried and found true that stick. You might call that the fundamental realization behind conservatism. Or if you want something truly radical, try Christianity and the idea that human beings are and by rights free and that we are made this way by our Creator. What he has done, no man may undo. Christianity and human freedom are the truly radical ideas and the real revolutions in our history. Marxism and all of its offshoots are merely reactionary, and in a pretty lunkheaded way, too.

Third is that weird fiction treats what is called the numinous. The numinous seems a philosophical or theological concept. I'm not a philosopher, nor am I a theologian, so I'll return to that fount of all knowledge, Wikipedia, which paraphrases Rudolf Otto (from 1923, the same year in which Weird Tales began) in stating that the numinous is "a mystery (Latin: mysterium) that is at once terrifying (tremendum) and fascinating (fascinans)." That works pretty well for me: weird fiction is about mysterious things that are at once terrifying and fascinating.

C.S. Lewis also commented on the numinous. In The Problem of Pain (1940), he wrote:

Suppose you were told there was a tiger in the next room: you would know that you were in danger and would probably feel fear. But if you were told "There is a ghost in the next room," and believed it, you would feel, indeed, what is often called fear, but of a different kind. It would not be based on the knowledge of danger, for no one is primarily afraid of what a ghost may do to him, but of the mere fact that it is a ghost. It is "uncanny" rather than dangerous, and the special kind of fear it excites may be called Dread. With the Uncanny one has reached the fringes of the Numinous. Now suppose that you were told simply "There is a mighty spirit in the room," and believed it. Your feelings would then be even less like the mere fear of danger: but the disturbance would be profound. You would feel wonder and a certain shrinking--a sense of inadequacy to cope with such a visitant and of prostration before it--an emotion which might be expressed in Shakespeare's words "Under it my genius is rebuked." This feeling may be described as awe, and the object which excites it as the Numinous. [Emphasis added.]

If terrifying equals dread and fascinating equals awe, then we have two prominent people in agreement as to what makes the numinous. I might add that Fate--but perhaps not Weird--acts as a rebuke. We believe ourselves to be so, so fine--We are geniuses! And we are forever rebuked.

Lovecraft had his say when it came to weird fiction. In "Supernatural Horror in Literature" (1927), he wrote:

The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain--a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space. [Emphasis added.]

I think you can read awe into Lovecraft's formulation of the weird tale. But his definition doesn't quite work for me. The chief reason might be that he wrote it in his typical overwrought and very pulpish prose ("our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space."). Another, though, is that he saw these unknown forces as being against us. I'm not sure that that's necessary. I don't think that Weird is against us. There may be cruelty in her workings, but that's only what we see on our end. She may carry us away, but for what purpose? We are merely human. We are not to know. In short, I believe the weird tale can be about weird forces, weird atmospheres, and weird events, but these need not be malign.

Again, maybe personality and biography must make their entrance. Lovecraft was not properly loved by his parents. I imagine that he extended that feeling of not being loved or cared for into the universe as a whole. In addition, he may have had a personal sense of insignificance and extended that to all of us. Lovecraft was also a materialist and an amateur astronomer. I suppose that, as such, he liked Cosmos (order) and feared Chaos (disorder). He did not believe in God. He probably resisted God, who sweeps into the heart and disorders it so that it might be put right again. God rebukes our genius. Without God, there is also Chaos, though of a different kind than exists in the physical universe. We see that in our world today, which is overfull with moral and intellectual chaos. There is also fear: we live in a world of fear. And, as we are finding now, there is also insanity. Without God and a belief in God, we--all of humanity--go utterly insane. Anyway, remember that Lovecraft fancied himself a figure from the Enlightenment and greatly admired two exemplars of that period, Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. Gothicism and Romanticism, which are in Lovecraft as well, were reactions to Reason. How do we make all of these things work with him? Maybe Lovecraft wasn't quite what he made himself out to be. In any case, fearing Chaos is not the same as discounting it. Lovecraft knew fear, terror, awe, and madness. He wrote very effectively on weird subjects and in a weird atmosphere. In fact, building atmospheres of awe and terror was one of his special talents. A writer--and a believer--like C.S. Lewis probably had less of a problem with these kinds of things, but notice that he used--and capitalized--the word Uncanny. Remember, too, that Lewis came from a Celtic culture, whereas Lovecraft was from an old Anglo-Saxon one. They all lived on the same islands, but maybe there has always been a divide between them, like Hadrian's Wall.

The quotes, again, are from Wikipedia.

Finally, there is the idea that weird fiction is about tentacles. Weird, I know. But there may be something to it. Except that I don't think a fascination with tentacles originated in weird fiction. In fact, I think it came from science fiction. And I'll have more about that when I write about the first issue of Weird Tales and its first cover story, "Ooze."

* * *

I was reading and writing about Weird earlier this month when Weird--call it Death instead--visited us again: last year at this time, we lost a sister. Now, a year and four days after losing her, we lost a brother. I do not invoke Weird lightly. I write this in all seriousness. Like I said, I don't believe Weird to be a force, nor a body, nor a spirit. Weird may not be the proper word for it. But there are workings in this world about which we may not know, and no one can explain to me that these things have happened.

My brother had a paper route when we were kids. Sometimes I helped him deliver the Indianapolis News to the people of our neighborhood. This was in Irvington, on the east side of Indianapolis. Named for Washington Irving, it's the same neighborhood in which C.L. Moore grew up fifty years before us and the same in which the Cornelius family, the printers/publishers of Weird Tales from 1924 to 1938, also lived. With his pay, my brother bought comic books, Conan the Barbarian and Kull the Conquerer among them. We read them and enjoyed them very much. We even drew our own Conan-inspired comic book called Barbarian Magazine. Later in life, my brother sought out and assembled a very good collection of Howard's works in paperback. They are still on his bookshelf.

I remember and hold on to my brother and my sister and my parents and all of the other family members and friends we have lost. Again, here are Beowulf's last words:

"Weird hath offcarried

All of my kinsmen to the Creator's glory,

Earls in their vigor: I shall after them fare."

But not now. Later. I hope later for all of us who are left. Let Death go away from our door. Let it no more carry any of us away.

* * *

Tentacles on the Cover of

Conan the Barbarian

|

| There were lots of tentacles on the cover of Conan the Barbarian. Here are just two tentacled covers. Top: Conan the Barbarian #32 (Nov. 1973), with cover art by Gil Kane and Ernie Chua. Bottom: Conan the Barbarian #45 (Dec. 1974), with cover art by Gil Kane, Neal Adams, and Crusty Bunkers. Others from the first one hundred issues include #25, #72, and #86. The images here are from Marvel Database, hence the lack of price tags and the cleaned-up images. |

|

| Tentacles are in the current art world as well. Here is a photograph by Rashmi Gill showing the raising of a sculpture called "Witness," created by Shahzia Sikander, in New York City. It's meant to honor a late Supreme Court justice. That's why she's wearing a lace collar. The hair is similar to a Hopi maiden's, but it's more like a pair of goat horns. Some people have called the statue demonic or satanic. It doesn't help that her arms look like the tentacles of the Octopus Woman who is attacking Conan on the cover above. If a male sculptor had done something like this, he would have been excoriated for mutilating the female form. Instead, I guess, this is an expression of grrl power. Notice that the tentacles are connected to her body on both ends. They look like tubes or conduits or spark plug wires. Is she actually a machine? A cyborg? An AI? A transhuman? Is she feeding into herself, reaching into herself? Is she a multi-limbed female version of the worm Ouroboros? On November 17, 2022, I wrote a little about Pete Townshend's Lifehouse project. In James Harvey's illustration, there are tubes or feeds going into the heads of dehumanized masses of people. They look something like the image above. Or maybe these are manifold Fallopian tubes. Could she be fertilizing and impregnating herself? "Witness" is a well-made work. The face, head, and neck are good. But it's also bizarre and antihuman. I guess this is the state of public art in America. We must tear down images of Abraham Lincoln and put up monstrosities like this one as replacements. There will be no end to this of course. Or maybe Weird will end it. |

Original text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley