I have been writing about anniversaries and will keep on that track after writing a couple of articles on the side. This one is about some of my recent reading and some ideas that came up as I read. The next one is about Joy Division, Star Wars, Bob Newhart, and Volkswagens, among other things.

Last night (I write on August 25, 2024), I finished reading a book called My Name Is Asya by Kira Michailovskaya. I have the Scholastic edition, translated by Catherine A. Burland, originally published in 1968 and reprinted in 1975. The original Russian edition was published in 1964 as Perevodchissta Intourista. I started reading this book several weeks ago. In between starting it and finishing it, I read a couple of other books. I'll get to those in a second.

My Name Is Asya is not a genre story of any kind. It's actually a true-to-life story about a young woman living in Leningrad and working as an interpreter for a Soviet-era agency called Intourist. As a child, the narrator, Asya, went through the siege of Leningrad. Now she is in her early twenties and just starting out in her career. Asya lives in the same house in which she lived during the siege. (She calls it "the blockade.") Also in the house are her Aunt Musa, who has raised her after the death of her parents, and several others. Asya tells her story, about her household, her friendships, her co-workers, her relationship with her new boyfriend Yuri, and her experiences with different groups of foreigners, including some happy Finns and a difficult French visitor called Madam Brand. Her story is often meandering, seemingly unfocused. It reads like a series of diary entries. Asya is a sensitive and likable heroine, and her prose is often powerful, insightful, and poetic.

I say that Asya tells her story, but it's not a straight story and doesn't have a linear plot. There isn't even a proper ending. You would have a hard time writing a summary of it. This is in fact women's writing in which the protagonist and the reader are immersed in feelings, emotions, colors, atmospheres, and relationships. (1) In that kind of writing, there isn't necessarily any up, down, forward, or back. There are few if any lines or vectors. Instead there are webs and sometimes fogs. In telling her story, Asya mixes the present and past tenses, so some things are happening now, others have already happened, and there doesn't appear to be any distinction between the two. We think of time as moving in a straight line. Maybe sometimes it doesn't. In reading My Name Is Asya, I was reminded of Boston Adventure by Jean Stafford (1944). (2) I don't remember much about that book. I read it a long time ago. One of the reasons that I don't remember much about it is that it doesn't have much of a plot. You might say that it's another immersive kind of story. In both stories, a young woman becomes connected to a sort of matron. I don't know what, if anything, that might mean. At least Asya escapes from hers, or, more accurately, hers goes away.

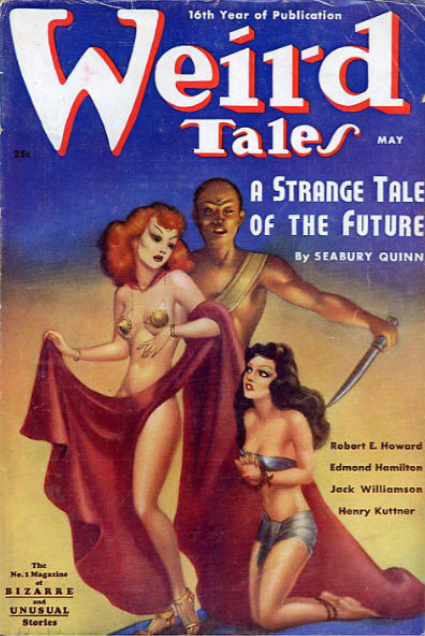

There is women's writing in genre fiction as well as in straight literature. Thank God for that. What a dreary trek it would be to read only things written by men, especially men seemingly without human experience, emotion, feeling, or relationships. Science fiction is notorious for that kind of thing. Too much science fiction is or was written by scientists, engineers, technologists, and other such kinds of men, who seem to lack humanity or to have truncated emotional lives or personalities. Put another way, you might say that science fiction is men's writing and is written in lines. (3) Weird fiction, on the other hand, has color and emotion, very often extreme emotion. It's very often written in moods and with atmosphere. Lines aren't always necessary. One of the strengths of the Henry Kuttner-C.L. Moore writing team is that he was good with the mechanics of plot, while she provided color and emotion. Although we think of Kuttner as a science fiction author, he got his start as an acolyte of H.P. Lovecraft and an author of weird fiction. And although C.L. Moore wrote science fiction, she is, in my mind, more nearly a weird-fictional author. And note the phrase "the mechanics of plot." Sometimes plots can be too mechanical. Kuttner, I think, was guilty of that sometimes. I would rather have a less-strong plot, as well as good and colorful writing, as in C.L. Moore's "Shambleau" (Weird Tales, Nov. 1933).

These are imperfect ideas: that science fiction is hard and linear, that it is built upon plot, and that--most imperfect of all--it is men's writing. Likewise imperfect: weird fiction is "soft" (or pulpy, like Cthulhu), perhaps non-linear, moody, colored, atmospheric, less reliant on plot, more nearly immersive. Weird fiction in general, Weird Tales in particular, very much appealed to women. Some of the foremost authors in its pages were women. That could hardly be said of science fiction magazines of the pulp era. So why was there that appeal? Why did women write so much weird fiction? And not only so much but so much that was so good? I don't have an answer to that, but I can speculate that it is because weird fiction is atmospheric, full of color, descriptive of the emotional states of its characters, very often non-linear, not always reliant on plot, and sometimes even departing from plot for its effect. Weird fiction is immersive, even oceanic. Sometimes even time is suspended, reversed, made irrelevant. Past is present and present is past--just as in My Name Is Asya. To take this idea even further, maybe to the point of breaking, we might say that weird fiction is sometimes uterine. (4) Better yet, we might say that it is sometimes wombed, from the Gothic--significantly from the Gothic.

Asya still lives in the womb of her childhood, her childhood home. Her story is based in that house and begins and ends there. There is little movement along the way. Although she sometimes travels in lines--with her boyfriend, she takes a train to the south of Russia--she doesn't really travel at all. (Travelers come to her.) Her life is oceanic. She lives in a web, not one made of lines, like those radiating from a railroad or airline hub, but a web in which the strands are inseparable from each other. There isn't really a plot in her story. Unlike her boyfriend Yuri, she isn't going in any particular direction. And she writes of the atmosphere in her city, which she loves, the rain and the white nights and the sun and rain and mist on the river Neva.

Houses figure pretty prominently in weird fiction and its forerunner and associate, the gothic romance. Just think of the cover of every gothic romance from the 1960s and '70s for an image of that house. There are houses in "The Fall of the House of Usher" and "William Wilson," both by Edgar Allan Poe. Contrast these almost housebound stories with a science fiction story that moves, like The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester, not only moves but moves in lines, whether broken or unbroken by its hero's jaunting. Raiders of the Lost Ark has its weird-fictional elements, but it's strong on plot and moves at breakneck pace along straight lines. You can write a coherent plot summary of it for your book report--if it were a book. Good luck with that if you have chosen My Name Is Asya or Boston Adventure.

So in between starting and finishing My Name Is Asya, I read Up in the Air by Walter Kirn (2001) and The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 by John Godey (Morton Freedgood) (1973). Both authors are of course men. Both stories are linear, literally so in that Mr. Kirn's book is--on the surface, no pun or irony intended--about flying on airlines, while Godey's book is set mostly in a subway train, which runs, of course, on a line and in a line. There is even a map at the beginning of the book that shows the line on which the Pelham train runs. This line is tipped with an arrow, and so takes the form of a vector. The equivalent in Walter Kirn's book is the narrator's itinerary, which is also linear, through time more than through space. One thing necessarily happens after another, although there is more to the story than that. Both stories also depend upon conveyances, that is, upon hard machines, also upon hard-technological processes. If Up in the Air had been written in 1960 about air travel in 2001, it would have been a science fiction story. That's how much technology plays a part in the story, as well as in our lives. In contrast, in her story, Kira Michailovskaya writes of webs of feeling and relationships. Her heroine Asya's trade is language and words. (To tell your name--"My name is Asya"--is one of the first exercises in a foreign language class.) We're not sure of when exactly the story takes place except that Asya remembers the blockade. In proximate terms, My Name Is Asya takes place in a never-never-land of time and a bound city. The blockade may have been lifted, but Asya essentially stays put.

It's not so simple as all of this, however, at least as far as Up in the Air goes. There are feelings and emotional and psychological states and relationships in that story. And if I'm not giving too much away, there is at the end a return homeward. Asya's story is about home and family, friendships and relationships. Again, it's based in the home and begins and ends at home. Up in the Air is based out of airports, hotels, restaurants, and casinos--one after another, in a line, by an itinerary. An airport hub and its radiating lines and connecting flights might look like a web, but you can travel only on one line at a time. But even while he's traveling, the narrator Ryan is thinking of home, family, and relationships, all of the best and most meaningful of which are with women. Asya's deepest and most lasting relationships are mostly with women, too. The building at the airport is called a terminal. It's the end of the line. In Up in the Air, there is an ending. In My Name Is Asya, there really isn't one. The narrator ends her account not long after breaking up with Yuri. You have a feeling at the end that her tomorrow will be like her today, and her many yesterdays.

The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 is more plot-driven and less interested in home or relationships. Again, it's based mostly in a subway train, also in various buildings that are not home. These milieux are mostly masculine, and the only notable women characters are related to home and relationships: the mayor's wife in their home; the radical girlfriend in the apartment that she opens up to her hippy-cop boyfriend; and the prostitute who, though her relationships are commodified, is still hoping to make it to her wealthy john's ménage in time to earn her day's pay. In her story, Asya's boyfriend is the radical ideologue. In Godey's story, it is the woman who plays that role. By the way, Asya's boyfriend is an engineer: he lacks human feeling and an ability to love. In a pulp-era science fiction story, he would be the hero and maybe even the author of the story. That's unfortunate. It would be nice to have had more humanity in the early days of science fiction. A second by-the-way: there is of course a plot in The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3, but the plot outside the story involves a plot from the inside carried out by the four hostage-takers. So, a double plot. One definition of plot here is meta, the other not. Like Ryan in Up in the Air, the hijackers have an itinerary: things have to go exactly as planned and by a set time schedule if they are to succeed. (5) Even the numbers of the title are in sequence. Maybe the four were hoping their hijacking of a subway train would be as simple as 1 2 3. As for the men, the leader is a man with no real feelings, or none that he cares to examine. Their plot breaks down when their relationships break down and emotion intrudes.

Asya travels on a train, too. She does that first with some Finnish tourists, then with her boyfriend. In other words, she leaves the womb or web of her home to travel on a line. But it is for the sake of developing her relationship with Yuri that she goes to the south of Russia. Unfortunately, it doesn't turn out well, as we know by the end it could not have done, for Yuri doesn't care about people. He doesn't see people as individuals, only as a faceless mass or a collective. Asya really doesn't mean anything to him, and he, like so many men, is of course a fool. And like every Marxist, socialist, materialist, or progressive in human history, he is also a fool.

As I have thought about lines versus webs, or of plot versus mood, color, and atmosphere, I have remembered a conversation I had with a friend who is a comic book artist. He knew Bernie Wrightson and has a similar approach in his work. Contrast the late Mr. Wrightson with Alex Toth, who distilled his drawings to essences, using few lines to show what he meant to show. Neither approach is better than the other. Both can be good. If mood is an element of storytelling, then Bernie Wrightson told stories, through mood, by drawing myriads of lines. And if conciseness and the movement forward of a plot are also elements of storytelling, then the use of a minimum number lines--line as essence--is simply a different way. These are not perfect parallels, but if there is a weird-fictional style in comic book art, Bernie Wrightson was, I think, one of its supreme practitioners. Alex Toth, on the other hand, worked a lot in animation, a more technology-dependent field (and one that forced him, I'm sure, to reduce the number of lines he drew), more specifically on science-fictional titles such as Space Ghost, The Herculoids, and Super Friends. Again, not perfect, but: in Bernie Wrightson's art, lines are maximized and used to create mood, while in Alex Toth's art, lines are minimized and used for delineation and to advance the plot, or for the sake of storytelling and continuity.

My Name Is Asya was published in the Soviet Union, of course during an era of communist and totalitarian domination of people's lives. I'm surprised that it made it to print, even if its suggestions of anti-communist--in other words human--sentiments are muted. But then it was written by a woman, and women can sometimes do things that men are not permitted to do. I have some quotes and insights from the book:

- Asya's boyfriend Yuri is working on an engineering concept, prefabricated boxes for building homes. His interest is not in the people but in the problem. In any case, he figuratively wants to put people into boxes, like mass-produced commodities into mass-market packaging. (Is Madam Brand called brand as a poke at westerners?) Asya has her career activities, too, but Yuri doesn't care about any of that. He doesn't see any importance in what she does. "The boxes are progressing," Asya writes, "slowly but always forward." We recognize that call--"Forward!"--as the cry of the radical, the socialist, and the progressive, whether he be a Nazi, a Bolshevik, or a twenty-first century Democrat in America. (p. 111)

- Aunt Musa warns Asya against Yuri:

"You keep harping on the same subject: Yuri says and Yuri says. I don't like that Yuri of yours. I am afraid of him."

"Why is that?"

"He looks like a lynx. His eyes are shifty."

I laugh.

"Go ahead, laugh. Only, be careful with your Yuri."

"What do you mean by 'careful'? Why?'

"I did not want to talk to you about it, I felt that you would figure it out for yourself. Now that I have begun I'll tell you. I think that nothing is sacred to him."

"Of course, he doesn't believe in God."

"I am not speaking of God. What I mean is, there is no kindness in him, no soul. And if there is no soul, there is nothing sacred."

"Sacred, soul--these are all strange concepts, Aunt Musa. Something that doesn't exist. In any case they are not material things. And Yuri is a man of the future, a rationalist. All our future life will be built on reason. What is reasonable cannot be bad. In the future, all these concepts--sacred, soul--will die and never return. There will only be the 'reasonable' and the 'unreasonable'." [. . .] (pp. 136-137)

(I wrote that My Name Is Asya is not a genre work, but in talking about the future--the future of human society--Asya in reference to Yuri has broached the exact subject matter of science fiction. Yuri is a materialist, a rationalist, in other words, one type of science-fictional or pseudo-scientific hero. [I'm looking at you, Karl Marx.] That makes him also one type of weird-fictional villain or antagonist, as we have seen. Very often, the hard-nosed materialist or science-minded person is also a psychopath. Although he isn't obviously a psychopath, Yuri is essentially lacking in a soul and he doesn't have any soul-to-soul connection with Asya. Asya in love doesn't see any of this and repeats Yuri's convictions. Older, wiser Aunt Musa does see it, though. Before the end of the book, Asya will see it, too.)

- How often have we read in weird fiction that "no words can describe the thing that I saw" or something to that effect. It's a kind of writerly laziness. Just try, Mr. Author. Please just try. In My Name Is Asya, the author deftly handled this problem. Weird-fiction authors take note as Asya first encounters Madam Brand:

I shall not attempt to describe the woman, although there are words in our dictionary especially created for such women: "enchanting," "captivating," "magic" and so on. If one should select the strongest words and arrange them in harmonious order, give them pure sound, then someone resembling her might result. (p. 170)

- Asya talks to her friend Valya who is upset. Asya assumes that she is in love. Valya goes on a rant in response:

"How do you know that? How do all of you know it all? What makes you all so clever? You are not people, you are computers--know all, and have an answer for everything. But life is not a formula and there are things that don't fit with your ideas. Things which don't even have a name in your language. You imagine and you know everything and that you have names and prescriptions already prepared for every occasion." (p. 194)

(I have commented a lot on this blog, but I wonder if others have, too, on the very strong and obvious connections among socialism and progressivism, scientism, and science fiction which are--with the frequent exception of science fiction--inhuman or anti-human. Aunt Musa sees it, so does Valya, though neither sees it in regards to science fiction, even if Marxism is a pseudo-scientific idea, in other words, a kind of science-fictional idea.)

- Unlike Ryan in Up in the Air, Asya doesn't fly in planes. She comes to a parting of ways with Yuri. "I feel rotten because we are different people," she writes. "I am a pedestrian and Yuri travels in planes." (p. 247) Asya realizes that her diploma is not rubbish and that Yuri's boxes are not important to her life. And so they part. (pp.246-247)

- Finally, Asya begins to move past Yuri. She paraphrases his thoughts: "I myself reject this drivel about individual people. There are no individuals, there is only the nation and the well-being and progress of the nation." She continues:

We all live under the same sun, but Yuri seems to have turned to the sun only one side of himself. The other has dried up, ceased to exist--the side which makes people, people. We are not threatened with the danger of being turned into animals, but we are threatened with the danger of being turned into machines. (pp. 260-261)

Those words were written six decades ago. They were prescient, just as true then as now. Transforming ourselves or allowing ourselves to be transformed into machines is a science-fictional concept, but it exists in science fiction only because it exists in real life. What we should want instead is to be human, like Asya and her family and friends. Human is infinitely better than machine, soul infinitely better than material, love infinitely better than process, family and friendship infinitely better than mass-living and collectivism. We're in a battle this year in America--as in every year the world over--and the lines are sharply drawn. (One case out of many where sharp and clear lines are better than fogs, mists, webs, and obscurities.) Let's be like Asya and choose human-soul-love-family-friendship over the alternatives.

Notes

(1) As a Scholastic book, it was meant for girls. And here is a difference between then and now: My Name Is Asya is not a children's novel, and yet it was packaged and sold to children with the expectation that they were up to the task of reading, understanding, and appreciating it.

(2) Jean Stafford was the daughter of a Western pulp writer named John Richard Stafford (1874-1966), aka Jack Wonder. He may have been the same man who wrote as J.R. Stafford. See The FictionMags Index for these names and their credits.

(3) I don't like the term "sci-fi," but I have used it in my title for the sake of assonance.

(4) Uterine is an inartful word to be sure, weakened in our language and for our purposes by its Latinate origin and its association with medicine. In the original, uterus also refers to "matrix," and that meaning works much better here, a matrix being something like a web.

(5) Up in the Air by Walter Kirn was published in 2001, but it must have been during the first three-quarters of the year, and I'll tell you why. Strangely, the dates of Ryan M. Bingham's itinerary, laid out in the front of the book, are inclusive of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. If the story had taken place that year, Ryan would never have reached his goal of one million frequent flier miles, and he would have been stuck in an airport somewhere in the West as his career came to an end. By the way, Walter Kirn is sometimes on TV. It's nice to see a novelist on television. It reminds me of the days when novelists, historians, philosophers, artists, and others were on TV pretty often and the United States was still a cultured country.