Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899) can be read simply as an adventure story, even if there is more to it than that. Like much of the best literature, it can be read at more than one level. Good genre fiction works that way, too. Merely sensational things are soon forgotten. Things of substance and quality stick.

In Conrad's novella, a seaman named Marlow, beginning in England, sets off for the Continent to secure work, then journeys to the west coast of Africa to carry out his assignment. He soon finds that he is to repair a boat, then to take it upriver to a remote place where a mysterious and intriguing figure named Kurtz resides and appears to reign. Conrad spent nearly twenty years of his life as a seaman. Those years included a monthlong trip up the Congo River and other trips across the world. Many of his works are about men and ships at sea.

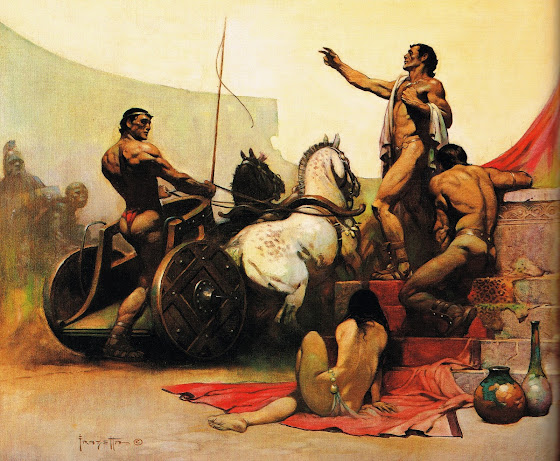

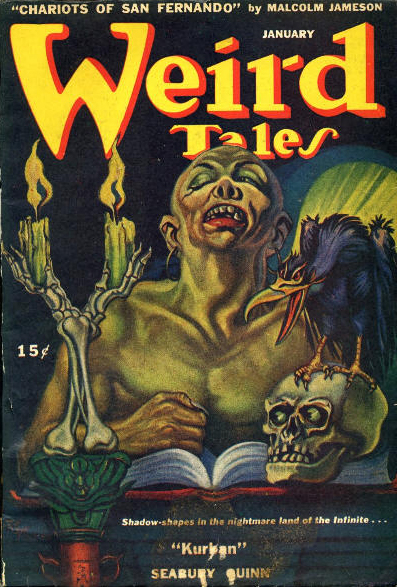

Again, not everyone can be Joseph Conrad, nor can everyone be Herman Melville or Jack London, who also went to sea, or Ernest Hemingway or James Jones, who went to war. But a writer ought to be able to draw from some other experience besides reading comic books, watching TV shows, and playing video games, which is how many of the authors in the Cosmic Horror Issue of Weird Tales seem to have spent their lives. Their characters follow their lead. Too many of them seem wrapped up in themselves. The lead characters in "A Ghost Story for Christmas" and "Night Fishing" are prime examples. Kurtz is one wrapped up in himself, too--everything to which he refers is his--but Marlow recognizes him as a great man. And he is (possibly), though great in a terrible way. One difference between Kurtz and too many of the characters in the Cosmic Horror Issue (their authors, too) is that he has gone somewhere and done something. They apparently have not. They have remained where they are, wrapped up in themselves, turned inward upon themselves like the worm uroboros. The old saying is that a man wrapped up in himself makes a small package. That is too evident in the pages of Weird Tales #367 and apparently, too, in the lives of its contributors. There are exceptions, but perhaps only barely. I will add that you don't have to look into your own navel and pick at your own little scabs--you don't have to examine your self-made inner voids when there is a whole world out there brimming with mystery and adventure. Even if you are bound to a place and a way of life, you might still turn loose your imagination and let it wander freely in the larger world. Good authors do that.

* * *

Another problem with the Cosmic Horror Issue of Weird Tales is that it is shamelessly, perhaps thoughtlessly, commercial. Its authors place the names of commercial products in their stories as if they had been paid to do so. In contrast, there is only one brandname in Heart of Darkness, Martini-Henry, the name of a rifle. That's a concrete detail. It's not product placement. In general, I think using the names of weapons, cars, cigarettes, and alcoholic drinks is probably okay in a work of fiction. The list of acceptable brandnames used after that must be, I think, pretty short, especially in a short story.

Joseph Conrad was conservative in an old-fashioned sense, meaning that he was aristocratic, perhaps reactionary, certainly skeptical of progress, and suspicious of liberal values. People seem to have forgotten that what they call capitalism is a liberal rather than a conservative institution. In Heart of Darkness, Marlow shows his disdain for commercialism and the relentless chasing after money that he witnesses in Africa. Most of the commercial products in his tale are cheap and lousy, or useless, like the pieces of brass wire used to pay African natives. There is one exception: ivory.

"The word 'ivory' rang in the air [Marlow remembers], was whispered, was sighed. You would think they were praying to it. A taint of imbecile rapacity blew through it all, like a whiff from a corpse." (Dell, 1960, p. 53)

That "imbecile rapacity" is seemingly everywhere in our world of today--even in the pages of fiction. That's just how it is, I guess. We are all human and so necessarily broken, warped, and twisted, at least in our worst moments and by our worst instincts. Art is supposed to rise above these things, though, and when an author of fiction uses a half-dozen or more brandnames in as many pages of his or her story, you can't help but smell the whiff of the commercial corpse. People have forgotten God, yet still they pray to the golden calf of money and material objects. And not just material objects but specific commercial objects, in other words products with brandnames. Many of those branded products have become not material at all--they are called services instead--yet still have the same taint and whiff of the commercial corpse. And now human beings seem to want to transform themselves into branded products, to make of themselves mere objects, to objectify and commodify themselves, a recipe, I should point out, for disquiet and unhappiness in the self-objectifying person. (As my philosophy professor, Mr. Pedtke, pointed out a long time ago, we are not things.) Anyway, I think that authors should cease with the product placement and the thoughtless and shameless deployment of brandnames. And editors should make sure that they do. Let fiction be art rather than advertisement.

To be continued . . .

Original text copyright 2025 Terence E. Hanley