"Can you believe, child, that there are gods of old who still live? Old gods, and powers that have survived the passing of their worshippers?"

--From The Citadel of Fear by Francis Stevens (Paperback Library, 1970, p. 204)

Francis Stevens, aka Gertrude M. Barrows Bennett (1883-1948), wrote the first serial by a woman to appear in Weird Tales magazine. (I'm pretty sure that Laurie McClintock was not a woman but a man.) All of those early serials were two-parters and so was hers. It is entitled "Sunfire," and it was in the issues of July/August and September 1923. "Sunfire" was the cover story for the July/August issue, making it the first cover story by a woman writer in "The Unique Magazine." The October issue also had a cover story by a woman, "The Amazing Adventure of Joe Scranton" by Effie W. Fifield (1857-1937). As it so happened, both women were born in Minnesota.

* * *

In 2004, academic Gary C. Hoppenstand asserted that Francis Stevens invented what he called dark fantasy. The title of his introductory essay, "The Woman Who Invented Dark Fantasy" in Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy by Francis Stevens (University of Nebraska Press, 2004), says it all. I disagree with him. From March 10 to May 13, 2015, I wrote a long series on Gertrude Barrows Bennett and her stories. In that series, I made what I believe to be a strong case that she was not the inventor of dark fantasy, which is, to be clear, an ill-defined sub-genre or sub-sub-genre of fantasy fiction. I believe saying that she was is an attempt to put something there that isn't there at all. It seems to me a lot of theorizing done after the fact, or an attempt to make the facts fit the hypothesis instead of the other way around. Beyond that, to say that this or that author "invented" a literary genre or sub-genre or sub-sub-genre is not to understand cultural or historical processes, which are, necessarily, evolutionary rather than discrete. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph. That was a discrete, technological event. He knew when he invented it that he had invented it. Did Francis Stevens ever use the term "dark fantasy"? Did she ever make any claims to inventing a sub-genre or sub-sub-genre that wasn't named until late in the twentieth century and has still not been adequately defined? The answer is of course no. "Dark fantasy" is of our time and not of hers. If anybody "invented" it, that happened long after she was gone. Anyway, to read what I wrote about Francis Stevens, aka Gertrude Barrows Bennett, click on the menu item on the right.

* * *

I write again today about Francis Stevens because of a couple of essays I have read recently regarding a man named Jonathan Cahn and his book The Return of the Gods, published in 2022. I have nothing to say about him or any validity or invalidity of his ideas. I would just like to point out that Mr. Cahn believes that there has been a revival--a literal revival, I think he means--of what he calls a Dark Trinity. This Dark Trinity is made up of three ancient--that is, pre-Christian, pre-Jewish, and very pagan--gods, Baal the Possessor, Asherah the Enchantress, and Moloch the Destroyer. The names are ancient. The epithets may be his. Differ with Mr. Cahn if you like. But it's clear to me that these ancient, hateful, and seductive gods have returned in one guise or another, most especially, I think, Moloch, to whom ancient pagans sacrificed their children. Look around us today and see the sacrifices we make of our own children, in the forms of abortion, transgenderism, drag, grooming, pedophilia, sexual mutilation, the use of puberty blockers, chemical castration, masking in schools, parks, beaches, and playgrounds, lockdowns, injections that are called "vaccinations," child trafficking, child pornography, the child sex trade, the sexualization of children, the politico-sexual indoctrination, abuse, mistreatment, and exploitation of children by parents, teachers, children's book authors, librarians, medical doctors, people in government, business, media, and entertainment . . . on and on it goes. If there is anything that will bring down upon us the direst of wrath and vengeance, it is this.

* * *

One of the problems with claiming that Francis Stevens invented dark fantasy is that there isn't any set definition of that term. Another is that dark fantasy was not so named until late in the twentieth century, either by Charles L. Grant (1942-2006) or Karl Edward Wagner (1945-1994). (That suggests that it did not exist until then.) Those two obstacles would seem insurmountable for any theorist: it doesn't matter how hard he might hypothesize or theorize, the academic cannot get his fine ideas over those two enormous humps. He doesn't have the power, no matter how many degrees he might have, no matter his position, reputation, influence, or prestige. It just isn't there.

* * *

Genres, forms, styles, and trends in popular culture may be recognized, described, and named. For example, according to Wikipedia, the term film noir was first applied to Hollywood movies of a certain type by Italian-French film critic Nino Frank (1904-1988) in 1946. The period during which film noir flourished began in about 1940 and ended in the mid to late 1950s. In other words, film noir was recognized as a style--and that style was named--contemporaneously to the making of the movies themselves. For another example closer to home, the New Wave in science fiction was described and named by various writers and critics in the period 1961 to 1968. That naming, too, was contemporaneous with the coming of the New Wave. Like the term dark fantasy, though, New Wave "has never been defined with any precision" according to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. The Encyclopedia doesn't have an entry at all on what is called dark fantasy, and the term dark fantasy isn't used at all in its entry on Francis Stevens except in reference to Dr. Hoppenstand's collection of her stories. So far he stands alone, albeit with an assist from Wikipedia, that purveyor of things that are and are not true.

So film noir and the science fiction New Wave were recognized, named, and described by writers and critics contemporaneously to the making of movies and stories in their respective styles or genres. If Francis Stevens was the inventor of what is called dark fantasy, then it obviously was not. "But there weren't any critics back then," you might say. "Pulp fiction was not studied or taken seriously," you might claim. And yet H.P. Lovecraft, a reader in vast realms, wrote and in 1927 published his seminal survey "Supernatural Horror in Literature." The word dark is throughout Lovecraft's essay. It's clear that he recognized a dark cast in historical and what was then contemporary fantasy fiction. But he didn't employ the word fantasy, using phantasy instead, in a different sense of the word, and nowhere in his essay does the name Francis Stevens appear. So if Francis Stevens invented dark fantasy, H.P. Lovecraft failed to see it, but we do. How smart we are.

I have one last example. Here in the twenty-first century, some people started to call a certain type of music from the 1970s and '80s "yacht rock." In other words, use of the term "yacht rock" was not contemporaneous with the music that is called yacht rock. It was applied only after the fact, an example of facts being forced to fit the hypothesis. Consider this idea: Francis Stevens as the inventor of dark fantasy is the "yacht rock" of criticism in fantasy fiction. And as you sail upon your yacht, listening to your music, be on the lookout for Fonzie jumping over a shark.

* * *

Gertrude Barrows Bennett was born in the late nineteenth century, in fact just one year after the publication of Friedrich Nietzsche's work The Gay Science (1882), in which he famously (or infamously) wrote: "God is dead." Nietzsche didn't kill God of course. He was more nearly acting like Dr. McCoy, observing as Dr. McCoy so often does, "He's dead, Jim." Except that maybe Nietzsche was a little more sanguine in his attitude about the death at hand than was the ship's doctor on board the Enterprise.

Anyway, if the one God was dead, then that would leave room for the old gods to come back. Perhaps they had lain sleeping, waiting for when the stars would be right for their return. Francis Stevens had one of her characters say, "Can you believe, child, that there are gods of old who still live?" "Believe it," Jonathan Cahn seems to be saying. And again, Gertrude Barrows Bennett seems to have foreseen what we would come to, in the same way that Mary W. Shelley, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jakob Burckhardt, Fyodor Dostoevsky, C.S. Lewis, and so many other conservative thinkers and writers foresaw. Progressives may have their grand plans and fine ambitions for all of us and for our shared future. But they never work. Always there are horrors and horrors.

* * *

I began this year writing about the Fates and their three Nordic counterparts, including Wyrd or Weird. I speculated that Weird came back out from under God during the nineteenth century, once God had weakened in the hearts of men. (Men weaken, God never.) Imagine: a word and a concept that was almost lost came back, and from the word and concept came a new-old genre of fiction, the subject, along with its authors and artists, of this blog. Thankfully Weird was never a god and never malicious.

* * *

Paganism came back in the nineteenth century, too, including in materialistic or atheistic systems of belief that burned and still burn like holy fires in the hearts of their adherents. Marxism, more generally socialism, is chief among these materialistic or atheistic systems, even if it has been transmuted into critical theory, DEI, transgenderism, identity politics, the culture of victimhood, and so on.

* * *

I believe that Gertrude Barrows Bennett was a believer, possibly a Roman Catholic. And not only was she a believer, she appears to have been firm in her faith. Her faith seems to have filled her heart and to have illuminated her works. I don't sense a woman struggling with her beliefs. Instead, she seems to have been entirely forthright and genuine and to have written with an ease that comes from complete conviction. In her story "Serapion," she had one character say to another: "[Y]ou seem different from any living man. You look like--I have seen the picture of a man with that light on his face." That man was nailed to a cross, the speaker remembers. Last year, when one of the Moloch State's great abominations was finally overturned by the Supreme Court--and by what we might see as divine intervention--I saw a news commentator on television. She is Shannon Bream, and she was positively glowing as she talked about what had just happened. She had "that light" upon her face. It came from within her, but it also came from the source of all light and all love. I will never forget that look. And I will always hold it as a bit of evidence in favor of the God that so many, including the followers of the old gods today, hate so much. In fact, isn't their hatred itself also evidence in favor of the one whom they hate?

* * *

You can believe in the old gods in a literal or a metaphorical sense. I'm not sure that it matters very much either way. If dark fantasy is the story of their return, then it seems to me that the authors of dark fantasy are in favor of their return. It hardly seems possible or logical that the inventor of a very dark genre would have had an opposing eternal light within her, that she--Gertrude Barrows Bennett, aka Francis Stevens--would be in favor of their return and against her one God when she was so obviously a believer. But maybe it took a believer to sense that the old gods were returning and to prescribe what we might need to defeat them again, to force them into exile again. H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), also a product of the nineteenth century, was supposed to have been a non-believer, a materialist and an atheist, but even he sent his old god Cthulhu back into exile. Even he was kindly enough towards humanity to spare us. And what of the readers and lovers of dark fantasy today? Are they so kindly? I'm not so sure. It seems to me that the world is so overfull of people who are themselves overfull of hatred for themselves and for all of humanity that they would just as soon see us all punished forever. Either that or destroyed forever. It is for people like them that dark fantasy is made, and--if it is in fact a genre or sub-genre of fantasy fiction--why it was not named or described until late in the twentieth century, just in time for our twenty-first. As Jesus Jones sang, the world started to wake up from history with the tearing down of the Iron Curtain. But we wouldn't have it. We wanted horrors, and so we have them. They are more subtle in our century than in the last, but they are horrors nonetheless.

|

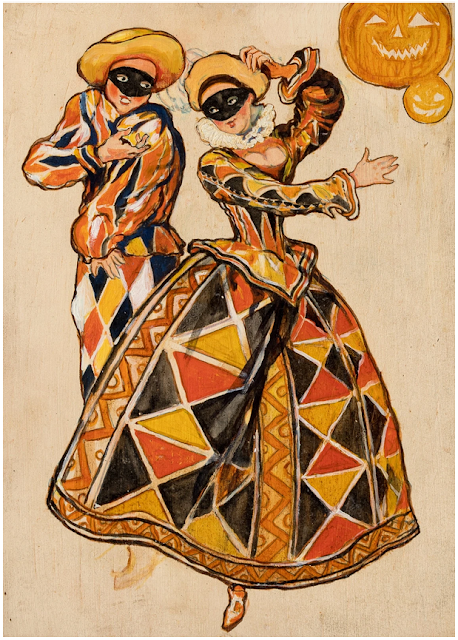

| A depiction of Moloch, god--or one of the gods--of the twenty-first-century Society-State and of worshippers of the Society-State. |

|

| The Triumph Of Christianity Over Paganism by Gustave Doré (1868?). Will this day come again? |

Original text copyright 2023 Terence E. Hanley