I guess I'm catching up on my viewing from 2015, the HBO TV series True Detective included.

Few people remember it today, but in its first incarnation, Weird Tales had a companion magazine called Detective Tales, later Real Detective Tales, which began publication in 1922. The publishers of these two magazines got into financial trouble about a year into their venture. One of the publishers, Jacob Clark Henneberger, gave up his interest in Detective Tales and held onto Weird Tales, which has had an on-and-off career in the nine decades since. Detective Tales carried on under a different publisher and became Real Detective Tales, then, in May 1931, simply Real Detective. The similarly titled True Detective, part of Bernarr Macfadden's True series of titles, began publication in 1924 and lasted until 1995. The point of all this is that the makers of the TV series True Detective seem to have intended to evoke pulp fiction and pulp imagery in their show. I think they succeeded. I would add that, despite the title, True Detective has much--maybe more--in common with weird fiction than with detective fiction.

I heard a lot about True Detective in 2015 when it first aired, and I can say after having seen it that the show is compelling. The co-stars, Woody Harrelson as Marty Hart and Matthew McConaughey as Rustin Cohle are excellent. (Note the symbolism in their names.) Matthew McConaughey is, as always, like a chameleon in portraying seemingly real people. A lot of the supporting actors are also good. I'll single out Brad Carter as Charlie Lange, the peckerwood ex-husband of the murdered woman, for his performance.

There is some clunky, inauthentic, and overly literate dialogue in True Detective, but over all, the characters speak in ways that are true to life. Rust is often sophomoric in his pseudo-philosophical musings. Hart registers proper skepticism and disgust at what he says. (I'm not sure that any actor is as good at disgust as is Woody Harrelson.) The main title sequence is very good, and the theme song is perfect for it, one of the best theme songs I've heard in a long time. The settings and scenery are great, as is the cinematography. There are some anachronisms, I think, and places where the screenwriter's politics show through. For instance, he takes unnecessary swipes at private schools, especially parochial schools, and at school choice. In reading about the show, I find that the screenwriter, Nic Pizzolatto, was raised Catholic. A lot of us were, but so what? Get over whatever it is that got your underwear in a knot and move on. To that end, the Rustin Cohle character is evidently an atheist, but at the end of the show he sees the light (literally). I imagine that was a bitter disappointment for any atheists watching and enjoying the show. Significantly, his penultimate vision--the one actually shown on screen rather than the one he describes from his wheelchair--enters the otherwise flat land of Louisiana (see Flatland below) in the form of a spiral (see The King in Yellow below) and through a circular opening in the spherical roof (see The Ring and Flatland below) of a decrepit building (see almost everything below).

I have to admit, the change in tone at the end of True Detective is a little jarring, but if being gored and hatcheted by the worst serial killer in history isn't enough to change your life, I don't know what is. The show also changes in its structure and viewpoint in later episodes. I'm not sure if those were good moves or not. There are also too many convenient developments (the owner of the green house is still living, still lucid, still available for questioning, and has an impeccable memory), too many things left hanging (who called the man who subsequently killed himself in his prison cell?), and too many missed opportunities on the part of the detectives (why didn't they talk to an anthropologist, a folklorist, and a botanist very early on in the case?), but over all, True Detective is a good show, I think, and well worth the viewing.

I said that True Detective seems to want to evoke pulp fiction and pulp imagery. Here are some possible sources of inspiration, or at least examples of creative minds arriving at the same points independently of each other:

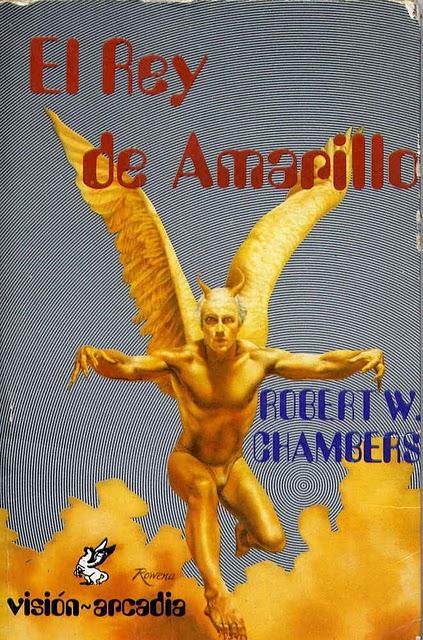

From The King in Yellow by Robert W. Chambers (1895): Carcosa (drawn from Ambrose Bierce); the King in Yellow; the viewing of the tape in True Detective vs. the reading of the play in "The Yellow Sign" as an experience that changes people's lives or damages their sanity; the secret symbol, in True Detective, a spiral, in "The Yellow Sign," the eponymous sign.

From H.P. Lovecraft (who drew from Chambers): the decadent and inbred family; the decrepit houses and other buildings; the backwoods setting; the circle or arrangement of stones in the woods at the the site of the cultist's rites; the super-secret and far-reaching cult; the secret and profane rites of the cult; the found object (in True Detective, the videotape).

From "Sticks" by Karl Edward Wagner (1974), The Blair Witch Project (1999) (both of which drew from Lovecraft), and the art of Lee Brown Coye: the found object in the videotape; sticks and stick lattices (there are sticks and lattices everywhere in True Detective; even the Cross can be seen as a stick lattice); drawings or murals on the walls of abandoned buildings; the old, decrepit, backwoods house; the murder of children; the super-secret cult.

From Twin Peaks (1990-1991): the opening sequence in which the body of a woman is found in some backwoods place; the otherwise eccentric storytelling, setting, and characters.

From The Silence of the Lambs (1991): the demented serial killer and his extensive house of horrors (if there is such a thing as the Gothic Baroque, the house and grounds of the serial killer in True Detective is it).

From The Ring (2002): the found object in the videotape; the viewing of the tape, which changes the lives of those who see it; the lone tree in the field; the repeated imagery of the circle or ring; the main title sequence in True Detective as a video montage like the contents of the tape in The Ring; the family with evil secrets; the decaying house of that family.

From Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbot (1884): talk of multiple dimensions beyond our own; flatness, circles, spheres, and other geometric or topological concepts (is a spiral merely a track made by a one-dimensional point as it moves in a certain way through a two-dimensional area, or, alternatively, the shadow in a two-dimensional area of a gyre spinning in three-dimensional space?; also, mention is made in the show of a psychosphere; also, sphere is another word for the different levels of the heavens, as in "music of the spheres"); flatness itself in the topography of Louisiana.

and

From the true-to-life Black Dahlia murder case (1947): The murder scene as a tableau for artistic, aesthetic, or personal expression; the ritualization of murder and of the preparation of the murder victim's body; the unsolved nature of the case.

As for philosophizing of Matthew McConaughey's character: I'm not sure where that comes from except from the minds of those who have given up hope or who are angry at and disillusioned by life and the world. It's not especially deep or serious-minded thinking, and though I'm no philosopher, I don't know of any formal source for the character's ideas or words. I'm with Woody Harrelson's character, though: Shut the eff up and let this vehicle we're riding in be an area of silent reflection. (But then the show would be far less interesting.)

One more thing: there is talk among writers and artists of "subverting" this or that. Trying to subvert things is an attempt at rebellion or innovation, very often a childish attempt. I would just say that when people claim that such-and-such "subverts" conventional storytelling, what they are really describing is something far simpler: it's called a twist, and genre writers and pulp writers use twists all the time. If you have never seen a twist before, or if you mistake a twist for a "subverting" of conventions, you haven't read very many stories. Next, I'll say that everyone in art, literature, politics, and society should remember the words of Ecclesiastes: there is nothing new under the sun. Nic Pizzolatto created a very fine piece of art, and he richly deserves the praise he has received, but I can't say that it subverts anything and I can't say that it's like nothing before it. (I don't know that he made those claims, only that viewers and critics tend to be carried away by hyperbole.) True Detective is just a really good piece of storytelling.

Updates, July 12, 2017

1. I see from another website that one of the books read by Rust is the collected poems of Theodore Roethke. Roethke was known for his recurring imagery of stones, bones, blood, sticks, and other natural objects. One of his most famous poems begins: "Sticks in a drowse droop over sugary loam." See "Sticks" and The Blair Witch Project above. Also, Roethke worked in greenhouses when he was young. Does green house (in True Detective) = greenhouse?

2. I see from that same website that flowers, especially in connection with sex, are part of the symbolism of True Detective. I hadn't thought much about that, but I'll add that flower parts--sepals, petals, etc.--are in whorls, a word similar in meaning to spirals.

3. Along those same lines, much of the imagery and many of the themes in True Detective have to do with sex, especially transgressive sex: pedophilia, adultery, sodomy, homosexuality, transvestism, bondage, group sex, pornography, sexting, sexual snuff films (the videotape). Even the spiral symbol can be interpreted as being related to transgressive sex. It's worth noting that all of the sex acts depicted outside of marriage are in one way or another transgressive. If I remember right, only one scene, a loving scene between Hart and his wife, shows a man and a woman in the missionary position (vs. what might be seen as pagan or pre-Christian alternatives). In contrast, the sex scene between Hart's wife and Rust shows her from behind, like the body of the murder victim at the beginning of the show. (By having sex with Hart's wife, Rust cuckolds him, i.e., places horns upon him, also like the body of the murder victim. Hart by the way is another word for an adult male deer.) I take all of that to be symbolic of a supposed moral decay that would have taken place over the years covered by True Detective, 1995 to 2012. Remember, True Detective was written by a Catholic. Remember, too, that 1995 was before cell phones and the Internet really took off.

4. In the climactic (not related to sex) scene, the main characters are on the floor of a domed building with a circular opening at the top of the dome. The building can be seen as analogous to an eyeball--i.e., a hollow sphere with a hole, aperture, or pupil in it--gazing upwards into the heavens (or spheres). (No wonder Rust sees a black hole, i.e., a kind of star but also a kind of spiral, through the aperture.) If the building is an eyeball, then maybe the stick-lattice representation of the Yellow King is at the fovea, a place also occupied for an instant, perhaps, by Rust. Significantly, fovea is Latin for pit, which is another word for abyss (for the Yellow King and his cultists) and trap (for Rust, who says early in the series that he feels like he's in a trap; the spiral symbol can also be taken as a labyrinth or maze, another kind of trap). Remember, Rust continually looks at his own eyeball in a mirror.

5. There is a lot of pagan, pre-Christian, post-Christian, and satanic imagery in True Detective, but other websites have gone into all of that, so I'll leave the analysis to them.

6. Whew!

Copyright 2017, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

.png)