Teacher, Author, Theosophist

Born February 21, 1885, Providence, Rhode Island

Died September 28, 1954, Ventura County, California

Bernice Thornton Banning was born on February 21, 1885, in Providence, Rhode Island, and graduated from Brown University in 1905 and the University of Wisconsin in 1910. In 1916, she set out for the Far East, to travel in Japan, China, and India, and to teach in Ceylon. She was appointed the first principal of the Buddhist Girls School in Ceylon and filled that post for a year, from January to December 1917. The school, founded by Celestina Dias, also known as Mrs. Jeremias Dias, was located in a house called "The Firs" on Turret Road in Colombo. Now called Visakha Vidyalaya, the school has since moved to larger quarters.

After completing her stint at the Buddhist Girls School, Bernice continued in her travels in Ceylon and India. In 1923, she applied for a passport at Madras, India, so that she might stay on there "for the purpose of study and recreation, on behalf of the Theosophical Society." The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky and her associates, established its International Headquarters in Madras, a suburb of Adyar, India, sometime before the turn of the century.

I don't know how long Bernice Banning remained in the Orient, but by 1930, she had returned to the United States and was living in Meiners Oaks in the Ojai Valley of Ventura County, California. The head of her household was the elder Margaret Reed, Bernice's companion in her Asian travels. Bernice continued in her work as a teacher. (She had taught at least as far back as 1910 when she was a university instructor.) She also wrote, though perhaps only a little for publication. Her story, "Finger of Kali," was published in the Winter 1931 (or Dec. 1930-Jan. 1931) issue of Oriental Stories. Oriental Stories, then in its second issue, would have been the perfect place for Bernice to display her knowledge of the Far East. The only other credits I have found for her are pieces written for The Adyar Bulletin, a theosophical publication, and printed in the July 1915 and February 1919 issues. Bernice T. Banning died on September 28, 1954, in Ventura County, California. She was sixty-nine years old.

After completing her stint at the Buddhist Girls School, Bernice continued in her travels in Ceylon and India. In 1923, she applied for a passport at Madras, India, so that she might stay on there "for the purpose of study and recreation, on behalf of the Theosophical Society." The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky and her associates, established its International Headquarters in Madras, a suburb of Adyar, India, sometime before the turn of the century.

I don't know how long Bernice Banning remained in the Orient, but by 1930, she had returned to the United States and was living in Meiners Oaks in the Ojai Valley of Ventura County, California. The head of her household was the elder Margaret Reed, Bernice's companion in her Asian travels. Bernice continued in her work as a teacher. (She had taught at least as far back as 1910 when she was a university instructor.) She also wrote, though perhaps only a little for publication. Her story, "Finger of Kali," was published in the Winter 1931 (or Dec. 1930-Jan. 1931) issue of Oriental Stories. Oriental Stories, then in its second issue, would have been the perfect place for Bernice to display her knowledge of the Far East. The only other credits I have found for her are pieces written for The Adyar Bulletin, a theosophical publication, and printed in the July 1915 and February 1919 issues. Bernice T. Banning died on September 28, 1954, in Ventura County, California. She was sixty-nine years old.

* * *

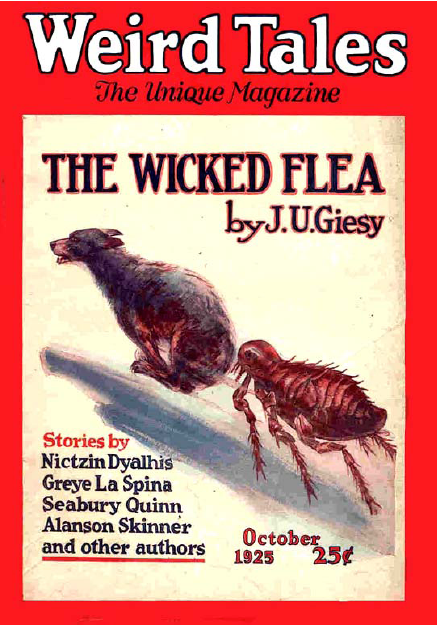

Bernice T. Banning hailed from Providence, Rhode Island, the hometown of H.P. Lovecraft of Weird Tales fame. Bernice was five years his senior and far more actively engaged in the world than was Lovecraft. But could they still have met? Chances are they did, or--if nothing else--that Lovecraft knew of the Banning family.

Bernice's father, Edwin Thomas Banning, was born on May 11, 1864. Although he came into the world in Donelson, Connecticut, Banning was descended from John Thurston (1750-1822) of Newport, Rhode Island. Banning attended Brown University in Providence but left school to become a draftsman and architect. On June 13, 1883, he married Isabel Thornton of Providence, originally from England. In 1910, the Banning family was enumerated in the U.S. Census in their residence at 88 Benefit Street in Providence. At that time, Lovecraft, aged twenty, was living at 598 Angell Street, about a mile and a half east of the Banning residence and on the opposite side of College Hill and the Brown University campus. Just down the street from the Banning house, at 135 Benefit Street, stood a large colonial house called the Stephen Harris Mansion. Reputed to be haunted, the house served as a model for Lovecraft's "Shunned House" from his story of the same name, written in 1924 and published in 1937. Lovecraft's aunt, Lillian Clark, lived in the house prior to his mother's death in 1921.

Like Robert Frost, Lovecraft was "one acquainted with the night":

I have walked out in the rain--and back in the rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain. . . .

Although he was a recluse and often on the verge of mental illness and physical and emotional collapse, Lovecraft knew his city well, walking over Providence at all hours, alone or with friends. He was an avid admirer of architecture and a thoroughgoing anglophile. He also had a strong bias in favor of old New England families like his own. The Banning family--tied to the Phillips family, that is, Lovecraft's mother's family--could no doubt have been an attraction and may even have been a distant relation through marriage. The distance to their home from his own was really no distance at all. And of course his aunt lived just a couple of blocks away, although it isn't clear to me that she lived on Benefit Street at the same time as the Banning family.

Lovecraft's story, "The Call of Cthulhu," might offer some clues as to possible connections. The second paragraph of the story begins: "Theosophists have guessed at the awesome grandeur of the cosmic cycle wherein our world and human race form transient incidents." Lovecraft mentioned theosophy in several other places in his work, and though it's unlikely he fell for its beliefs, there was probably something there for him, at least as a source of ideas, mood, or atmosphere. Bernice Banning was of course interested in theosophy, traveling halfway around the globe to study at its world headquarters. Second, Lovecraft alluded to "a widely known architect with leanings toward theosophy and occultism [who] went violently insane" at the time that Cthulhu's island crypt rose from the ocean floor. There isn't any indication that Banning was the model for Lovecraft's architect, but was there any other architect closer at hand? Finally, the narrator of "The Call of Cthulhu" is a Bostonian named Francis Wayland Thurston, the same surname as Banning's ancestor.

Edwin Thomas Banning left Providence and settled in San Diego in 1912, where he continued in his practice. At that time, Lovecraft would have been just twenty-two years old and in the depths of a personal--even existential--crisis. He may not have known or cared that the Banning family had departed. Banning is listed in Edan Hughes' Artists in California, 1786-1940, though I think only briefly. He died on May 18, 1940, in San Diego. I suspect that if Lovecraft didn't know them personally, he knew of the Banning family and would have seen them in the street, at the market, or on the streetcar. He no doubt walked by their door many times in his ramblings over that old city of Providence.

Bernice T. Banning's Story for Oriental Stories

"Finger of Kali" (Dec. 1930-Jan. 1931 or Winter 1931)

Further Reading

Girasol Collectables has reprinted the complete Oriental Stories/Magic Carpet Magazine. You'll find Bernice's story in those pages. Otherwise, I don't know of any sources for her stories or biography.

Bernice's father, Edwin Thomas Banning, was born on May 11, 1864. Although he came into the world in Donelson, Connecticut, Banning was descended from John Thurston (1750-1822) of Newport, Rhode Island. Banning attended Brown University in Providence but left school to become a draftsman and architect. On June 13, 1883, he married Isabel Thornton of Providence, originally from England. In 1910, the Banning family was enumerated in the U.S. Census in their residence at 88 Benefit Street in Providence. At that time, Lovecraft, aged twenty, was living at 598 Angell Street, about a mile and a half east of the Banning residence and on the opposite side of College Hill and the Brown University campus. Just down the street from the Banning house, at 135 Benefit Street, stood a large colonial house called the Stephen Harris Mansion. Reputed to be haunted, the house served as a model for Lovecraft's "Shunned House" from his story of the same name, written in 1924 and published in 1937. Lovecraft's aunt, Lillian Clark, lived in the house prior to his mother's death in 1921.

* * *

Like Robert Frost, Lovecraft was "one acquainted with the night":

I have walked out in the rain--and back in the rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain. . . .

Although he was a recluse and often on the verge of mental illness and physical and emotional collapse, Lovecraft knew his city well, walking over Providence at all hours, alone or with friends. He was an avid admirer of architecture and a thoroughgoing anglophile. He also had a strong bias in favor of old New England families like his own. The Banning family--tied to the Phillips family, that is, Lovecraft's mother's family--could no doubt have been an attraction and may even have been a distant relation through marriage. The distance to their home from his own was really no distance at all. And of course his aunt lived just a couple of blocks away, although it isn't clear to me that she lived on Benefit Street at the same time as the Banning family.

Lovecraft's story, "The Call of Cthulhu," might offer some clues as to possible connections. The second paragraph of the story begins: "Theosophists have guessed at the awesome grandeur of the cosmic cycle wherein our world and human race form transient incidents." Lovecraft mentioned theosophy in several other places in his work, and though it's unlikely he fell for its beliefs, there was probably something there for him, at least as a source of ideas, mood, or atmosphere. Bernice Banning was of course interested in theosophy, traveling halfway around the globe to study at its world headquarters. Second, Lovecraft alluded to "a widely known architect with leanings toward theosophy and occultism [who] went violently insane" at the time that Cthulhu's island crypt rose from the ocean floor. There isn't any indication that Banning was the model for Lovecraft's architect, but was there any other architect closer at hand? Finally, the narrator of "The Call of Cthulhu" is a Bostonian named Francis Wayland Thurston, the same surname as Banning's ancestor.

Edwin Thomas Banning left Providence and settled in San Diego in 1912, where he continued in his practice. At that time, Lovecraft would have been just twenty-two years old and in the depths of a personal--even existential--crisis. He may not have known or cared that the Banning family had departed. Banning is listed in Edan Hughes' Artists in California, 1786-1940, though I think only briefly. He died on May 18, 1940, in San Diego. I suspect that if Lovecraft didn't know them personally, he knew of the Banning family and would have seen them in the street, at the market, or on the streetcar. He no doubt walked by their door many times in his ramblings over that old city of Providence.

Bernice T. Banning's Story for Oriental Stories

"Finger of Kali" (Dec. 1930-Jan. 1931 or Winter 1931)

Further Reading

Girasol Collectables has reprinted the complete Oriental Stories/Magic Carpet Magazine. You'll find Bernice's story in those pages. Otherwise, I don't know of any sources for her stories or biography.

|

| Bernice T. Banning, her passport photo from 1923. |

Postscript, April 13, 2012

In reading Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons by George Pendle (2005), I have found out that Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986), so-called "World Teacher" of theosophy, settled in Ojai, California, in 1922. He spent most of the rest of his life there and associated himself with other theosophists, including Rosalind Edith Williams Rajagopal (1903-1996). Rosalind founded the Happy Valley School, now the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley, in 1946, in Ojai. (The school is no doubt named after Annie Besant, the British theosophist.) I wonder if Bernice Banning and Margaret Reed followed Krishnamurti to Ojai, and if Bernice taught at Happy Valley after its founding.

Revised December 9, 2018.

Text and captions copyright 2011, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

In reading Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons by George Pendle (2005), I have found out that Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986), so-called "World Teacher" of theosophy, settled in Ojai, California, in 1922. He spent most of the rest of his life there and associated himself with other theosophists, including Rosalind Edith Williams Rajagopal (1903-1996). Rosalind founded the Happy Valley School, now the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley, in 1946, in Ojai. (The school is no doubt named after Annie Besant, the British theosophist.) I wonder if Bernice Banning and Margaret Reed followed Krishnamurti to Ojai, and if Bernice taught at Happy Valley after its founding.

Revised December 9, 2018.

Text and captions copyright 2011, 2023 Terence E. Hanley