The second feature in Weird Tales #367, the Cosmic Horror Issue (2023), is an essay called "When the Stars Are Right: The Weird Tales Origins of Cosmic Horror" by Nicholas Diak. Mr. Diak has an advanced degree from the University of Washington. Presumably he is an American. He is a writer and scholar interested in movies, music, comic books, and horror fiction, including the works of H.P. Lovecraft. His interests, then, match up with those of the other contributors to this issue. It looks like Weird Tales #367 is still, with this essay, the work of insiders. Mr. Diak has his own website. You can reach it by clicking here.

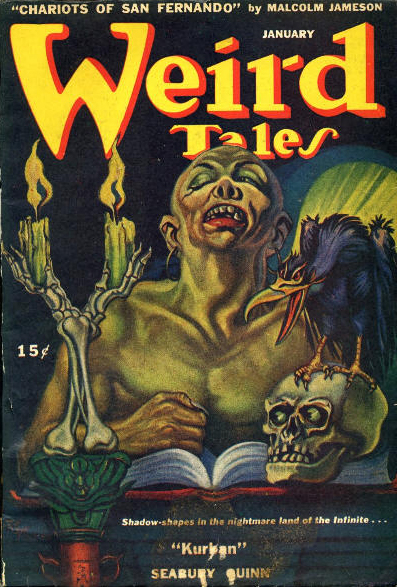

"When the Stars Are Right" is an essay of six pages all together. This includes a full-page illustration on the title page, four reproductions of Weird Tales covers from the 1920s through the 1940s, and a half-page illustration of tentacles at the end. That illustration is essentially filler. An enlarged part of it is used as the backdrop for the title page. Tentacles as a shorthand image representing weird fiction have become a cliché or, to use an academic kind of word, a trope. I wonder if we can all resolve to end it, to write and create new things and put some of the old ones (maybe some of those Old Ones, too) behind us. After all, new is the promise of the first essay in the Cosmic Horror Issue, editor Jonathan Maberry's brief introduction in "The Eyrie."

Nicholas Diak's essay begins with an epigraph. This is the second to appear in Weird Tales #367. The first is from Edgar Allan Poe's poem "The City in the Sea." The second is from H.P. Lovecraft's poem "Nemesis," from Weird Tales, April 1924, or one hundred and a half years ago.

Mr. Diak's essay is scholarly or academic in its structure and tone. For example:

This article aims to celebrate cosmic horror by showcasing its unique attributes: genre staples, meta and self-referential qualities, repudiation of reality, its sense of awe, and finally its delightfulness. (p. 15)

So maybe at last we have a definition of cosmic horror. Even so, I'm not sure that it's quite complete. Also, I see three different things mixed up in that sentence. First are things from outside the story itself, namely "genre staples" and "meta and self-referential qualities." I take "genre staples" to be just another term for conventions, tropes, or clichés. I have been writing about those qualities of what is called cosmic horror already in this series. I have also written about meta-references and self-references.

Next are things that are part of the story itself or that exist within the story as part of its plot, theme, mood, and so on, namely "repudiation of reality" and a "sense of awe." I think these attributes extend into weird fiction and fantasy fiction as a whole. A sense of unreality, even if it is fleeting, is an essential part of weird fiction, I think. So is a sense of awe. Awe is a feeling we have all experienced (I hope) as we gaze into the night sky, in other words, into the cosmos. I'm not sure that anyone has ever felt horror in so gazing. Maybe I'm wrong. I think it would take a sick person to have that kind of feeling in contemplating the stars.

Finally, there is the "delightfulness" of cosmic horror. Mr. Diak explains what he means later in his essay when he calls cosmic horror fun to read. I won't argue with that. I'll just point out that fun is a reaction of the reader. And so we have preparations made by the author in the first pair of attributes, the story as a kind of sealed container of the second pair, and the reader's reaction in the last single attribute.

There are lots of names of authors in Mr. Diak's essay, including a list in the first paragraph. That list includes the name of another contributor to the Cosmic Horror Issue. If an essay can have a meta-reference or self-reference, then this is it. Mr. Maberry is also mentioned here, towards the end. I think we'll have to take Nicholas Diak's word for it that Weird Tales is enjoying a period of "current prosperity." Count me skeptical. Otherwise I don't see these names as examples of name-dropping or listing. You already know how I feel about those kinds of things.

I'll admit that I like reading non-fiction about science fiction, weird fiction, and fantasy. I like to see a mind at work. I like history and criticism that have behind them a thesis rather than just as chronicles of events. That's why I can say that Love and Death in the American Novel by Leslie Fiedler is an exciting book. So I'm predisposed to liking a well thought-out essay. Unfortunately, the space here is too limited, and I'm still not sure we have a very good--or at least a very thorough yet concise--definition of cosmic horror as a sub-genre or sub-sub-genre of fantasy fiction.

In his essay, Nicholas Diak looks at stories by Lovecraft as well as by Robert Bloch, Robert E. Howard, C. Hall Thompson, and Clark Ashton Smith. I was surprised to find Thompson's name in this essay. As far as I can tell, he has seldom been talked about in the company of the other authors mentioned here. In 2019, I wrote a series on C. Hall Thompson. You can access the first part of what I wrote by clicking here. I have at least one more part to write in that series, based on information I did not have in 2019. I hope to get to that soon.

Like I said, there is a scholarly and academic tone and academic-type language, too, in "The Stars Are Right." For example, there is in the first paragraph the use of the passive voice, one of the scourges of academic writing. The author calls "The Call of the Cthulhu" a "text" instead of what it is, which is a story. The phrases "cosmic horror texts" and "cosmic horror canon" appear on the last page of the essay, also the word "tropes." It's good to notice and point out the use of tropes or clichés in any kind of storytelling. Those things are probably okay in storytelling for children. They should probably be left out of it for adults. "Text" and "canon" are pretty horrible words, though. My advice to any scholar is to throw them away. They're not texts, they're stories. And the only real canon I know of is in the Catholic Church.

* * *

Nemesis

by H. P. Lovecraft

Thro' the ghoul-guarded gateways of slumber,

Past the wan-moon'd abysses of night,

I have liv'd o'er my lives without number,

I have sounded all things with my sight;

And I struggle and shriek ere the daybreak, being driven to madness with fright.

I have whirl'd with the earth at the dawning,

When the sky was a vaporous flame;

I have seen the dark universe yawning,

Where the black planets roll without aim;

Where they roll in their horror unheeded, without knowledge or lustre or name.

I had drifted o'er seas without ending,

Under sinister grey-clouded skies

That the many-fork'd lightning is rending,

That resound with hysterical cries;

With the moans of invisible daemons that out of the green waters rise.

I have plung'd like a deer thro' the arches

Of the hoary primordial grove,

Where the oaks feel the presence that marches

And stalks on where no spirit dares rove;

And I flee from a thing that surrounds me, and leers thro' dead branches above.

I have stumbled by cave-ridden mountains

That rise barren and bleak from the plain,

I have drunk of the fog-foetid fountains

That ooze down to the marsh and the main;

And in hot cursed tarns I have seen things I care not to gaze on again.

I have scann'd the vast ivy-clad palace,

I have trod its untenanted hall,

Where the moon writhing up from the valleys

Shews the tapestried things on the wall;

Strange figures discordantly woven, which I cannot endure to recall.

I have peer'd from the casement in wonder

At the mouldering meadows around,

At the many-roof'd village laid under

The curse of a grave-girdled ground;

And from rows of white urn-carven marble I listen intently for sound.

I have haunted the tombs of the ages,

I have flown on the pinions of fear

Where the smoke-belching Erebus rages,

Where the jokulls loom snow-clad and drear:

And in realms where the sun of the desert consumes what it never can cheer.

I was old when the Pharaohs first mounted

The jewel-deck'd throne by the Nile;

I was old in those epochs uncounted

When I, and I only, was vile;

And Man, yet untainted and happy, dwelt in bliss on the far Arctic isle.

Oh, great was the sin of my spirit,

And great is the reach of its doom;

Not the pity of Heaven can cheer it,

Nor can respite be found in the tomb:

Down the infinite aeons come beating the wings of unmerciful gloom.

Thro' the ghoul-guarded gateways of slumber,

Past the wan-moon'd abysses of night,

I have liv'd o'er my lives without number,

I have sounded all things with my sight;

And I struggle and shriek ere the daybreak, being driven to madness with fright.

* * *

In his poem, Lovecraft used the word abyss. That word and a similar word or idea--void--will come up again in this series. It seems to me that there are two common and I guess connected ideas behind the stories in the Cosmic Horror Issue, the abyss or the void being one of them. Also, note Lovecraft's allusion to "the far Arctic isle." Was he referring to Hyperborea? Or to Ultima Thule? Are these two imaginary places related somehow?

In reading about Ultima Thule, I came across Edgar Allan Poe's poem "Dream-Land," from 1844. I see some similarities between "Dream-Land" and "Nemesis." Note the archaic contractions in both, also the use of such words as "tarns" and "ghoul" or "Ghouls," and again the reference or allusion to Ultima Thule. Remember, too, that Lovecraft wrote a story called "The Colour Out of Space." Did he get his title from Poe's phrase "Out of SPACE--Out of Time"?

* * *

Dream-Land

by Edgar Allan Poe

By a route obscure and lonely,

Haunted by ill angels only,

Where an Eidolon, named NIGHT,

On a black throne reigns upright,

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule--

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of SPACE--Out of TIME.

Bottomless vales and boundless floods,

And chasms, and caves, and Titan woods,

With forms that no man can discover

For the tears that drip all over;

Mountains toppling evermore

Into seas without a shore;

Seas that restlessly aspire,

Surging, unto skies of fire;

Lakes that endlessly outspread

Their lone waters--lone and dead,--

Their still waters--still and chilly

With the snows of the lolling lily.

By the lakes that thus outspread

Their lone waters, lone and dead,--

Their sad waters, sad and chilly

With the snows of the lolling lily,--

By the mountains--near the river

Murmuring lowly, murmuring ever,--

By the grey woods,--by the swamp

Where the toad and the newt encamp,--

By the dismal tarns and pools

Where dwell the Ghouls,--

By each spot the most unholy--

In each nook most melancholy,--

There the traveller meets, aghast,

Sheeted Memories of the Past--

Shrouded forms that start and sigh

As they pass the wanderer by--

White-robed forms of friends long given,

In agony, to the Earth--and Heaven.

For the heart whose woes are legion

'T is a peaceful, soothing region--

For the spirit that walks in shadow

'T is--oh, 't is an Eldorado!

But the traveller, travelling through it,

May not--dare not openly view it;

Never its mysteries are exposed

To the weak human eye unclosed;

So wills its King, who hath forbid

The uplifting of the fring'd lid;

And thus the sad Soul that here passes

Beholds it but through darkened glasses.

By a route obscure and lonely,

Haunted by ill angels only,

Where an Eidolon, named NIGHT,

On a black throne reigns upright,

I have wandered home but newly

From this ultimate dim Thule.

* * *

Original text copyright 2024 Terence E. Hanley