Fate magazine was first published in the spring of 1948, seventy-four years ago this season. The publisher was Clark Publishing Company of Chicago, founded by Raymond A. Palmer (1910-1977) and Curtis G. Fuller (1912-1991). The first cover story was about the first sighting of flying saucers, made by Kenneth A. Arnold (1915-1984) less than a year before, on St. John's Day, June 24, 1947. Fate was preceded by Doubt, the magazine of the Fortean Society, first published in or about 1937. Whereas Doubt was a specialized title and had a small circulation, Fate was intended for the general reading public and was marketed as such. It was digest-sized from the beginning and looked for all the world like a science fiction/fantasy magazine. Palmer, after all, was a canny editor, publisher, and marketer. He had a pretty good idea of what would sell as the 1940s reached their end and the 1950s began.

Fate was also preceded by Weird Tales, which was first in print a quarter of a century prior to that first issue. If I have counted correctly, Weird Tales was in its 249th whole issue in the spring of 1948. Although it had come down in the world--that happened in general to pulp magazines during the 1940s--Weird Tales was still chugging along in the old pulp format. It finally conceded in September 1953 and switched to digest-size. Only half a dozen issues remained after that: Weird Tales finally came to an end--you could say it met its fate--in September 1954.

At first glance, Fate and Weird Tales have nothing to do with each other. That's where having a collection of early issues of Fate comes in handy. I won't claim that there is a strong connection between these two magazines, but from what I have seen, readers, writers, and even one artist seem to have migrated from Weird Tales to Fate in the 1950s. I think the two magazines must have served some of the same readership. In addition, there appears to have been a kind of continuity from weird fiction into Forteana. Or maybe it was the other way around. Or I guess it doesn't matter when you're dealing with continuities. As Charles Fort wrote, "One measures a circle, beginning anywhere." I should note that the words fate and weird--in its original sense as a noun rather than an adjective--are practically synonymous.

* * *

I'll start with the writers.

This isn't necessarily a complete list, but in the issues of Fate that I recently acquired from the collection of the late Margaret B. Nicholas and William Nicholas, I found stories and articles from the following writers who also contributed to Weird Tales:

- Dulcie Brown (1899-1978)-Dulcie Brown made one contribution to the Weird Tales series "It Happened to Me." She was a Fortean and a writer of several letters to Fate. The magazine must have been right up her alley, and I can imagine her joy and pleasure once she discovered it, early or late. You can read more about Dulcie Brown in Joshua Blue Buhs' very interesting blog From an Oblique Angle, at the following URL: https://www.joshuablubuhs.com/blog/dulcie-brown-as-a-fortean

- Arthur J. Burks (1898-1974)-Arthur J. Burks wrote about Voodoo and other things in Weird Tales. A former U.S. Marine (if there is such a thing), he recounted an experience from his military days in "I Have Healing Hands" in the April 1957 issue of Fate. By coincidence, Fate reprinted William B. Seabrook's account of zombies in Haiti in that same issue.

- Mary Elizabeth Counselman (1911-1995)-Despite the fact that she wrote more stories than almost anyone for Weird Tales, Mary Elizabeth Counselman is, I think, a neglected author. In September 1962, Fate published her article "I Saw Them Take Up Serpents," about snake-handling in Southern churches. Note the confessional title.

- L. Sprague de Camp (1907-2000)-L. Sprague de Camp isn't quite in the same category as the other writers in this list. After all, he was only a minor contributor to Weird Tales but a very successful author of science fiction and fantasy, as well as factual, historical, and biographical works. For Fate, he wrote fairly often, mostly or exclusively on archeological subjects.

- Vincent H. Gaddis (1913-1997)-Vincent H. Gaddis contributed one brief story for Weird Tales but, over the years, many articles for Fate. An early member of the Fortean Society, he in fact specialized in Forteana, and it was Gaddis who popularized the idea of a Bermuda Triangle that gobbles up ships and planes. The earliest articles for Fate that I have for him are "America's Most Famous Ghost Story" and "Hollywood Superstitions," from Fall 1948, the third issue of the magazine. There may have been others before that.

- Donald E. Keyhoe (1897-1988)-Like Burks, Donald E. Keyhoe was a former military man. He contributed to Weird Tales before World War II. After the war, he became interested in--if not obsessed with--flying saucers. Fate published an interview with Major Keyhoe in August 1959, a year and a half after Mike Wallace had interviewed him on TV.

- Everil Worrell Murphy (1893-1969)-Everil Worrell was a pretty consistent contributor to Weird Tales from 1926 to 1954. In April 1957, Fate published her short article "Million-Dollar Message" as part of its regular feature "My Proof of Survival." Arthur J. Burks was in the same issue.

Stories and articles by previous contributors to Weird Tales seem to have evaporated at the end of the 1950s. There may be some significance in that. Note that most of the writers I have listed here were of the same generation, one that reached retirement age in the early 1960s. Also, pulp magazines were coming to an end as the 1950s ended, too. Even magazines that had made the switch or had started out as digest-sized titles were having a hard time by the end of the decade. As for Fate, it made a switch, too, going from painted covers to mostly text covers in 1958-1959. I think the last painted cover was in November 1959, just in time for the decade to end. Was that to cut costs? Were cover artists moving on to paperback books, men's magazines, and movie posters? Was the competition with other genre-type magazines drying up as those titles reached their end? I can't say. (1)

* * *

Fate published what is supposed to have been non-fiction. Weird Tales on the other hand was a magazine of mostly fiction, poetry, and illustration. Still, there are some connections between the two. Most obviously, Fate continued in its publication of supposed non-fictional accounts written by readers. In Weird Tales, these were called "It Happened to Me." That series lasted for eleven installments, from March 1940 to November 1941. Fate had at least two confessional-type features, "My Proof of Survival" and "Report From the Readers." Of course, confessional magazines and features had been around for a long time before that. The 1950s had their confessional genre-movie titles, such as I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). Before that there was I Walked with a Zombie (1943), which was produced by Val Lewton (1904-1951), a onetime contributor to Weird Tales.

* * *

As you might expect from the title, a big part of Fate of the 1950s and '60s had to do with real-life strokes of fate. These accounts are brief but numerous. On page after page and in issue after issue, there are stories of how the cruelest of fates befall mostly undeserving people. There are so many of these accounts--moreover they are written in such a way--that you get the idea that the editors took real pleasure at other people's pain, suffering, and cruel deaths. (2) There's a name for stories like these. They're called contes cruels and they are a staple in weird fiction. Think "The Pit and the Pendulum" by Edgar Allan Poe. The popularity of the conte cruel in weird fiction may have something to do with what Jack Williamson called the Egyptian-Hebraic roots of the anti-utopian story. My plan is to get back to my series on Utopia and Dystopia in Weird Tales and to explore that idea further.

* * *

There is something shabby and squalid in weird fiction that doesn't as often obtain in science fiction. In looking over my new collection, I have noticed that the art on the covers of science fiction magazines of the 1950s is often clean, showing the clean machine-lines and machine-curves of spacesuits and rocketships; the topological flawlessness of toroid space stations and disc-shaped spacecraft; the pristine surfaces of planets and their deep, luminous, unpolluted skies; the spotless and uncluttered depths and vastnesses of outer space, illuminated by the crystalline light of myriad stars. This is the future after all. It's bound to be better--certainly cleaner and purer--than the present, especially once we escape this earth. Very often in these scenes, people shrink away to almost nothing. Being biological in nature, people are of course impure and messy and unclean, at least in the minds of the stereotypical physical scientist, mathematician, or engineer. The human element is therefore reduced in much of science fiction art.

Some of the covers of the Raymond A. Palmer-type magazines are like this, too, but many others are lurid, sketchy, violent, chaotic. Some are exploitative, almost to the point of being in bad taste--or beyond bad taste into new territories of badness and tastelessness. The shudder pulps of the 1930s and some cheaper weird fiction/fantasy magazines of the 1940s are like that, too. Weird Tales is far less so. I think "The Unique Magazine" strived to remain in good taste in fact. Despite the nudity so often depicted, Margaret Brundage's covers are harmless confections. They look like they are made of cake frosting and spun sugar. (Her medium was mostly chalk pastel.) I should point out that a lot of science fiction art was created using an airbrush, in other words, a machine. That tool renders a machine-like perfection to textures, curves, and contours, unlike the less well-controlled and more organic paintbrush, crayon, or pencil. This is not to take anything away from airbrushed artwork: I could look at Alex Schomburg's paintings all day long and into the night and never get tired.

* * *

Anyway, if you look at the advertisements inside Weird Tales, you will see what I mean by shabbiness and squalor. Those same kinds of ads continued in Fate. Ads about numerology, "ancient wisdom," Ouija boards and planchettes, mystic this, metaphysical that. Ads about Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, "startling revelations," astrology, palmistry, graphology, the Tarot, "psychic development," and every other kind of esoterica. There are office addresses and post office boxes where you can write to get yours today, whatever it happens to be. I imagine shabby and squalid places on the other end, places housing not only run-of-the-mill charlatans and conmen but also every kind of crank, crazy, and crackpot, some or many of whom, to their credit I guess, probably believed in what they were peddling. Men wearing turbans or toupees and dyed van-dyke beards, women with piled-up hair, hard with hairspray, their faces covered in pancake makeup, all of them dressed in cheap, fake, gaudy, or threadbare costume, wearing shoes with cracked leather and worn heels and soles, hoping to gain a few bucks by trying or claiming to be able to heal the equally cracked and worn souls of their fellow human beings. Maybe these are stereotypes I have gleaned from our vast popular culture, of all the cheap, fake, grasping, squalid psychics, mediums, soothsayers, and occultists in all of those old movies and TV shows and stories, for example Raymond Chandler's 1940 detective novel Farewell, My Lovely. In seeing these advertisements, my mind went right away to another example, the Starry Wisdom Temple in Strange Eons by Robert Bloch (1979) (pp. 94ff.), with its cluttered, musty interior, hung with old drapes and smelling like a funeral home. This shabbiness and squalor has since come back into the real world, in the cult-like lifestyle and squalor of the Manson family, the squalid and terribly tragic ending of so many people at Jonestown, and the equally squalid ending of the Heaven's Gate cult just twenty-five years ago this season.

* * *

In doing research on Dianetics/Scientology a few years ago, I looked at street views of that organization's branch offices. So many of them were cheap, rundown, practically abandoned. At around that time, I was approached by a Scientologist at an event. He was on crutches, his leg in a cast or wrappings. These were my thoughts after I had talked to him: I thought you people were able to cure such things. I thought you were able to make of yourselves superior men. Anyway, I can imagine ads for Dianetical and Scientological "products" and "services" of the 1950s as looking much like those I have seen in Weird Tales and Fate.

Speaking of that, you will find ads for Mathison electropsychometers in Fate but without any mention of Dianetics or Scientology. The inventor of these gadgets, Volney G. Mathison (1897-1965), was also a contributor to Weird Tales. He was briefly associated with L. Ron Hubbard (1911-1986) but broke with him in the early to mid 1950s. (Breaking with Hubbard seems to have been a theme back then, as we'll see.) Coincidentally or not, Scientology grew out of Dianetics in 1954, the year Weird Tales reached its end. More than one writer for Weird Tales became interested or involved in Scientology. We should remember, though, that Dianetics/Scientology was the offspring of a depraved writer of science fiction and not at all of weird fiction, at least not that appeared in Weird Tales. And in case you don't remember it, I'll remind you in a future part of this series.

By the way, Heaven's Gate was a science-fictional rather than a weird-fictional cult. So is the long-enduring quasi-cult of Flying Saucers, which are actually Fortean phenomena, even if Forteana seems to be more closely connected to weird fiction than to science fiction . . . I guess I don't have all of these things puzzled out just yet.

* * *

We're all searchers, and I don't want to hit anyone too hard with the foregoing sections or take anything away from others and their searching--from their endeavoring to persevere as the old Indian in The Outlaw Josey Wales says. We all have to search and find our way if we can. We all must do our best to persevere in this life that so often seems so incomprehensible, in which there is so much pain and suffering, much of which is or seems to be needless and meaningless.

What I'm trying to get at, I guess, is that maybe people read weird fiction and Forteana for reasons far different from the reasons they read science fiction. With science fiction, maybe the reader looks to the future and the things of the future--flawless science and perfect machines--for some kind of escape or salvation. (Are escape and salvation the same thing in some people's minds?) With weird fiction and Forteana, the past and the things of the past seem to be the attraction, even if they are--or maybe because they are--musty, dusty, threadbare, squalid, shabby, or falling into ruins. Charles Fort (1874-1932) spent his working life in libraries where old, dusty, worm-eaten books, journals, and manuscripts are kept. His personal life was squalid. His professional mission was the exhumation of the past. (The past as revenant.) Weird fiction, gothic fiction, horror, and fantasy are typically about the past and the things of the past, too. Very often, the setting in these genres is an old house or castle or abbey--lonely, desolate, run-down, decaying, falling into ruins. Like Fort, the weird-fictional hero discovers in his searching a grimoire or a whole library of such dusty tomes. Within their pages are the keys to all understanding . . .

Maybe the reasons for reading weird fiction and Forteana show through in the readers themselves and the things they want and buy and look for in the back pages of their favorite magazines. And maybe weird fiction and Forteana go together in continuity. Further still, maybe science fiction is discontinuous with those two genres--maybe with all others, too--a strange thing to consider, but maybe it's true after all.

Notes

(1) I read somewhere that the last science fiction pulp magazine was published in 1958. I don't know what that magazine was or whether the year is right. Keep in mind, too, that there was talk in the late 1950s and early 1960s that science fiction as a whole was dying.

(2) The 2021-2022 version of these stories is Covid death-porn, which so many people seem to revel in.

|

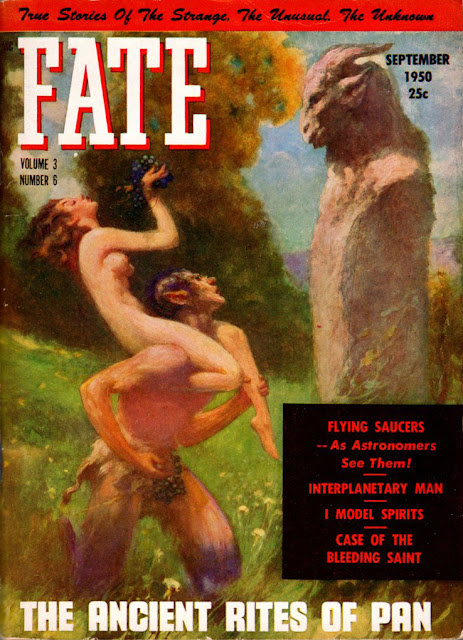

| Virgil Finlay (1914-1971) created the art for the last issue of Weird Tales, published in September 1954. A month later, his artwork was on the cover of Fate. Fate wasn't exactly a successor to Weird Tales, but it seems to me that it served some of the same readership. Finlay's cover illustration is a simple, one-stop demonstration of that idea. Unfortunately, most of the art on the cover and inside of Fate is unsigned and no credits are given. Too often this is how the world treats artists. (Note the Florida Man blurb on the cover. Go, Florida Man!) |

Text copyright 2022 Terence E. Hanley