The Utopia of Lost Worlds & the Lost Worlds of Europe

A long article to last for a while . . .

Utopia literally means "not a place," alternatively "no place" or "nowhere." (1) It has never existed and can't exist except in the imagination, but it's where the imagination goes from time to time. In attempting to bring about Utopia, the political imagination has instead created horrors. (We may soon see a bit of that for ourselves.) It is only in the literary imagination that Utopia truly lives.

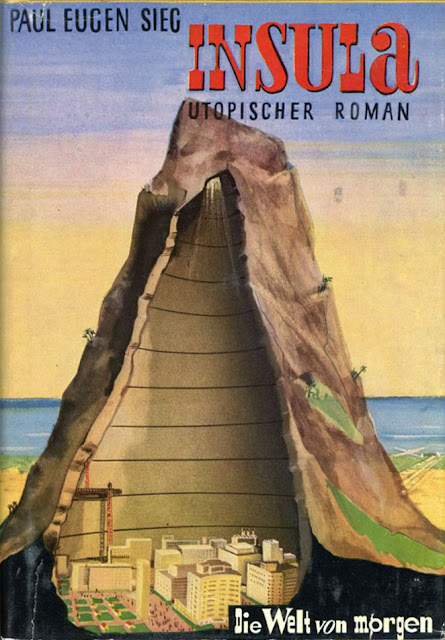

The original Utopia, created by Thomas More (1478-1535), is an island, discovered in a world then and now called new. The twenty-first century reader of genre fiction might recognize More's Utopia and places like it as Lost Worlds. For decades--for a century or more--authors set their adventures in these places--in worlds that are at once lost and new--and the satirical and high-literary ambitions of the original utopian chroniclers gave way to romantic and adventurous popular fiction. As the known world grew and the unknown shrank away, Lost Worlds became a place to wander not for the reasoning mind but for the adventuring heart.

It seems to me that Lost Worlds are those that are lost in any civilized age. An escape from civilization seems to be a key element in the Lost Worlds story. I'm not the first to reach that kind of conclusion. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by John Clute and Peter Nicholls (update, 1995), does these things a lot better than I do. Here is that source on the British author H. Rider Haggard (1856-1925):

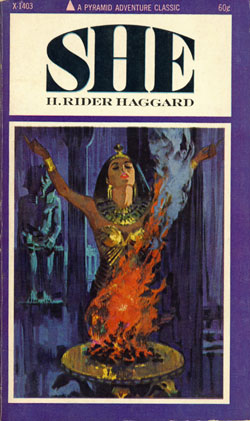

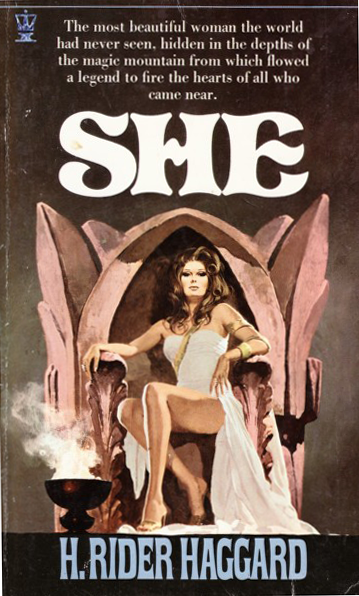

With his third and fourth novels, King Solomon's Mines (1885) and the even more successful She: A History of Adventure [1886-1887] HRH was catapulted to fame [. . .]. These novels of anthropological sf remain his most famous; they established a pattern he would follow for the rest of his career. That pattern might best be described as a central model for Edgar Rice Burroughs and the science-fantasy subgenre whose popularity attended the latter's revival in the 1960s: it is a pattern in which realistic portraits of the contemporary world (in HRH's case South Africa) are combined with backward-looking displacements (in his case invoking Lost Worlds, immortality and reincarnation) to give a general effect of deep nostalgia. [Emphasis added.] (pp. 531-532)

And again:

Not all of these books [the Allan Quatermain books] could be described as science fantasy, but all project that sense of desiderium--the longing for that which is lost--that lies at the heart of true science fantasy [. . .]. [Emphasis again added.] (p. 532)

Part of that bears repeating for the reader of Weird Tales: "the longing for that which is lost [. . .] lies at the heart of true science fantasy."

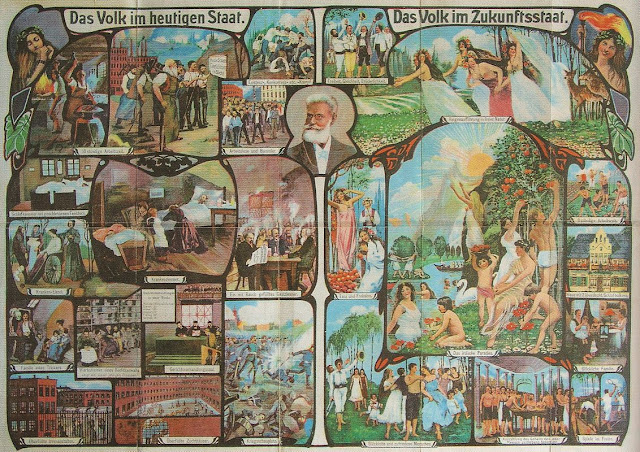

For the first two or three centuries, utopian stories tended to be progressive, yet still geographic: Utopia is now, but it is somewhere else on Earth. In the progressive-minded nineteenth century, utopian stories, in association with progress then being made in the sciences, were cast into the future: Utopia is not in the now on Earth, but in the will-be or might-be of the future, either here or on other worlds.

At the same time all of that progress was going on, there was also a conservative or nostalgic reaction. Men wanted to hold on to the Lost Worlds of the past even as they disappeared. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries there were Gothic and Romantic reactions to Reason and Neoclassicism. In the late nineteenth century, there were Lost Worlds fantasies and romantic, medieval, anti-technological Utopias. The Pre-Raphaelite artists and members of the British Arts and Crafts movement wanted to turn back the clock. So did American makers of utopian communities. In the late 1800s there were Dystopias, too, a new genre, originally known, I think, as anti-utopias. Reaction was literally in the word itself. These tended to be written by conservatives, such as the American Anna Bowman Dodd (1858-1929).

So it looks like in the nineteenth century, conservative-minded people looked backward with pangs of nostalgia. (Again, Edward Bellamy's title is ironic.) The past was being lost--whole worlds were being lost. The future--especially a scientific and technological future--must have looked to them like a nightmare-in-the-making. Matthew Arnold's poem "Dover Beach" (published in 1867), in which the "Sea of Faith" has long since retreated, comes to mind. Here is the famous closing stanza:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

In his book Conservatism (Van Nostrand, 1956), Peter Viereck had Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) as a conservative. In reading about him now, I wonder whether Arnold was indeed conservative and whether "Dover Beach" might actually be an ironic poem, again on the subject of nostalgia and a yearning for the Lost Worlds of the past.

When Utopia migrated from a place somewhere on the current Earth into the imagined future, it entered into the realm of science fiction, a genre that tends towards progressivism, as opposed to science fantasy--weird fiction, too--which is nostalgic or backward-looking, as The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction notes. There it stayed for a while, but maybe only for a while. "Utopian thought in the last half century" observes the Encyclopedia, "has to a large extent disassociated itself with the idea of progress; we most commonly encounter it in connection with the idea of a 'historical retreat' to a way of simpler life [sic]." It adds: "Even the recent past has been restored by the momentum of nostalgia almost to the status of a utopia [. . .]." (p. 1261) It was no coincidence (or at least I don't think it was) that the two most recent of the works offered as examples, Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach (1975) and Time and Again by Jack Finney (1970), were published in the 1970s, when some people--older writers and fans, I think--feared that science fiction was dying. Maybe what was dying was the old progressive, utopian brand of science fiction, the supremely confident, outward-bound Gernsbackian and Campbellian brand of the 1920s through the 1930s and '40s. I think I'll have more on that later. Meanwhile, I will refer you once again to "The Gernsback Continuum" by William Gibson, published in 1981, just three years before his landmark Gothic science fiction novel Neuromancer came out.

* * *

Things were being lost, worlds were being lost, and with them possibilities, too. Here's another thing that was no coincidence (or at least I don't think it was): a conservative, nostalgic, romantic, or anti-science, anti-technology, anti-civilization reaction came along at about the same time that the conservation movement began in America. (Conservative and conservation are from the same root after all.) Yellowstone National Park, the world's first, was established in 1872. King Solomon's Mines was published in 1885. The National Geographic Society was founded in 1888. (2) Percival Lowell (1855-1916) discovered Lost Worlds on Mars in the 1890s and early 1900s, and novelist Edwin Lester Arnold (1857-1935) sent his new Gulliver there in 1905. The first national wildlife refuge was already two years old by then. The establishment of the first national monument followed in 1906. In between, several prominent Americans and one prominent Norwegian got together to form the Explorers Club of New York (1904). (3) Then, in 1912, both John Carter of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes made their debut. I sense that all of these were efforts to discover, explore, conserve, and ultimately escape into places in danger of being lost in one way, and appealing because they were already lost in another. I sense that many, if not all, were exercises in nostalgia.

I have one more type of Lost Worlds to enter into this gazetteer: the Lost Worlds of Europe. When I was a teenager, I read King Solomon's Mines again and again. The only rival to it in my reading was The Prisoner of Zenda by Anthony Hope (1863-1933). Published in 1894, The Prisoner of Zenda was the original Ruritanian romance. Scads more followed, including the Graustark novels of my fellow Hoosier, George Barr McCutcheon (1866-1928). The Lost Worlds of Europe became pretty prominent in weird fiction and fantasy. I guess I could write a whole article or series of articles on them. I would have to do a lot of research first, though. I invite readers to send in their own examples or lists, especially from the pages of Weird Tales. That kind of research could help build the case that Lost Worlds, descended from Utopia, are a more conservative or nostalgic genre, thus one suited to the traditional, conservative, or backward-looking genres of weird fiction and fantasy.

Anyway, the Lost Worlds of Europe are also prominent in movies, from Frankenstein (1931) to Brigadoon (1954) to The Mouse That Roared (1959) to The Last Valley (1971) to The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). Mission: Impossible (1966-1973) is full of fictional countries, many of them in Europe. Seemingly every one has a Rollin Hand lookalike as its dictator or generalissimo. Shades of Rudolf Rassendyll. In The Prisoner (1967)--no Zenda--a different kind of prisoner, called Number 6, is held in a miniature European Lost World, which also happens to be a Dystopia. He has a doppelgänger, too. You'll find out who it is in the last episode. (4) The Lady Vanishes (1938), begins in a Ruritanian country. In that film, Michael Redgrave plays a kind of ethnomusicologist, like Alan Lomax, recording the works of the worst and most forgettable folk culture in Europe before it is lost. (5, 6) He had better hurry. The members of that family seem to be the last practitioners of it, although there is an insurance commercial playing right now with perhaps a related family and culture living upstairs, joyously and tirelessly clogging away . . .

To be continued . . .

Notes

(1) "Nowhere," thus the anagram in the title of Erewhon: or, Over the Range, a Lost Worlds novel (or romance) written by Samuel Butler (1835-1902) and published in 1872.

(2) The first issue of National Geographic magazine was dated September 22, 1888, and for more than a century things went pretty well, I guess. Then, in January 2017, National Geographic jumped the woke shark and began trading in gnostic and anti-scientific claptrap. According to Wikipedia, the Walt Disney Company has, since 2019, owned a "controlling interest in the magazine." What Disney has done to Star Wars and Marvel can only be done to National Geographic, too. I think Disney owns the John Carter and Tarzan franchises as well. It's probably just a matter of time before John and Jane swap sexes and names.

(3) Cryptozoology, an investigation into the fauna of Lost Worlds, dates from that period as well. Antoon Cornelis Oudemans (1858-1943) is considered its founder with his book The Great Sea Serpent, published in 1892.

(4) So would the sequel to The Prisoner of Zenda be called Return to Zenda? You know, a lowly British postal employee has to deliver some packages to Ruritania, only to discover that he is the spitting image of the King . . .

(5) That's Lomax, not Lorax. The Lorax was another famous conservationist. (Alan Lomax knew of a Utopia, too. It's called "The Big Rock Candy Mountains.")

(6) The opening sequences in The Lady Vanishes try a little too hard to be funny. It doesn't work very well for me. I sense a kind of mean-spiritedness in some of it, a peculiar brand of snobbery and disdain for people of supposed lower classes or what used to be called "races." George Barr McCutcheon did the same kind of thing in Graustark: The Story of a Love Behind a Throne (1901). Holding people up for ridicule because of their perceived low status is kind of a cheap way towards humor. Writers should work a little harder and use a little more imagination. (This is coming from someone who just sprang two puns on you.)

|

The Prisoner of Zenda by Anthony Hope was published in 1894. This illustration I think is from 1895 and is signed Hooper. Maybe that was the British engraver and illustrator William Harcourt Hooper (1834-1912), who worked in old forms. To that point: there is nothing new under the sun until there is. Although The Prisoner of Zenda was the first of a new genre, the Ruritanian romance, it received an old treatment in this illustration: the dark, creaky Gothic castle from the previous century once again looms over the European landscape.

William Harcourt Hooper worked with William Morris (1834-1896) of the Arts and Crafts movement. Among his other works, Morris wrote News from Nowhere, a utopian story (1890), and The Well at the World's End, a famous fantasy (1896). Morris was also a socialist, further evidence that a link exists between socialism and utopian thinking in general, and a backward-looking, nostalgic kind of reactionary conservatism. Put another way, the Socialist wants a return to the Middle Ages and stasis, to a stable and ordered society in which there are masses of immobile serfs below, a permanent, select, and élite aristocracy above (of which he, of course, is a member, if not leader), and no ambitious, energetic, grasping, usurping bourgeoisie in between. |

|

In 1896, Parker Brothers came out with a Prisoner of Zenda board game. Here the castle is white and the scene sunny and bright. Maybe this is the castle of the good guys, while the previous one is Black Michael's. Anyway, we might think of merchandising and multimedia marketing campaigns as twentieth century, but here is an example of both from the nineteenth. My contention is that the elements of our current popular culture date from 1895-1896 (some from a couple of years earlier). Here is another piece of evidence for that. Stratego, another board game (though of the twentieth century) has a Ruritanian look to it, too, but I think that's because both Stratego and The Prisoner of Zenda were drawn from the essentially Ruritanian imagery of the real-life, nineteenth-century Europe of Napoleon, Metternich, Bismarck, and so on. Most of that came crashing down, I think, in and with the Great War.

It's at once comic and tragic to look at photographs of military men of the old Europe taken in the 1920s and '30s: here are relict grand, sculpted moustaches; bright plumes and cockades and cordons; brass buttons, fringed epaulets, and braided piping--here are airs of dignity, rectitude, and pride; things and ideas and ways that can no longer survive in the postwar world, originating as they have in the world that has been lost if not destroyed outright in the apocalypse of the trenches. It seems to me that in the nineteenth century the military uniform, especially the officer's uniform, still had its trappings of a proud and confident aristocracy. In the twentieth, it became democratic, and the officer in the field came to look just like his men. Herman Melville's phrase "the Dark Ages of Democracy" comes to mind. |

|

| Here's a nice painted cover of the Classics Illustrated comic book version. Unfortunately, the artist did not sign his or her work. |

|

| Lastly, a paperback edition by Magnum with a classic 1960s-1970s men's magazine-type cover. This isn't the edition I had when I was a kid, but I did have the Magnum edition of King Solomon's Mines, with a cover perhaps by the same artist. I think these are from the 1970s. (No, that is not a green light saber.) |

Original text copyright 2021, 2023 Terence E. Hanley