Fine Artist, Illustrator, Short Story Writer, Novelist, Playwright, Children's Book Author

Born May 26, 1865, Brooklyn, New York

Died December 16, 1933, New York, New York

Robert W. Chambers lived the kind of life any aspiring writer might envy. Talented, popular, and prolific, he wrote nearly one hundred books and used the proceeds to fund a lavish estate, a sizable art collection, an active club life, frequent trips abroad, independent wealth, and plenty of leisure time. He was an outdoorsman, a lepidopterist, a collector, an expert on certain antiquities, and in his early years, a very successful artist and illustrator, counting Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) and other artists and writers among his friends. Many of Chambers' stories were adapted to film in his lifetime and after. Chambers' wife, French-born Elsa Vaughn Moller, called "Elsie" and daughter of a European diplomat, bore him one son, Robert Edward Stuart Chambers. The younger Chambers, who also went by the name Robert Husted Chambers (1899-1955), followed in his father's footsteps as a writer. The Chambers family also included Chambers' brother, the New York architect Walter Boughton Chambers (1866-1945), who designed landmarks in his native city and other northeastern states.

Wealth, talent, fame, family--it all added up to a great success, yet, as far as I know, there has never been a book-length biography of Robert W. Chambers. And in the minds of many, Chambers squandered his talent on popular novels produced at a rapid pace and settling somewhere below the ken of literature. "Stuff! Literature!" Robert W. Chambers scoffed in a 1912 interview. "The word makes me sick!" His disdain for literary endeavor may have been the fox talking about the grapes. Either way, it assured that his work would become dated and seldom read in later years. In his time, he was called "the Shopgirl Scheherazade" and "the Boudoir Balzac." Today, Chambers' reputation rests almost solely on a single book, his second, entitled The King in Yellow, published in 1895.

In his survey of the genre, H.P. Lovecraft wrote--in his "Supernatural Horror in Literature" (1)--two long paragraphs on Chambers. I'll quote them in their entirety here:

Very genuine, though not without the typical mannered extravagance of the eighteen-nineties, is the strain of horror in the early work of Robert W. Chambers, since renowned for products of a very different quality. The King in Yellow, a series of vaguely connected short stories having as a background a monstrous and suppressed book whose perusal brings fright, madness, and spectral tragedy, really achieves notable heights of cosmic fear in spite of uneven interest and a somewhat trivial and affected cultivation of the Gallic studio atmosphere made popular by Du Maurier’s Trilby. The most powerful of its tales, perhaps, is "The Yellow Sign," in which is introduced a silent and terrible churchyard watchman with a face like a puffy grave-worm's. A boy, describing a tussle he has had with this creature, shivers and sickens as he relates a certain detail. "Well, sir, it's Gawd's truth that when I 'it 'im 'e grabbed me wrists, sir, and when I twisted 'is soft, mushy fist one of 'is fingers come off in me 'and." An artist, who after seeing him has shared with another a strange dream of a nocturnal hearse, is shocked by the voice with which the watchman accosts him. The fellow emits a muttering sound that fills the head like thick oily smoke from a fat-rendering vat or an odour of noisome decay. What he mumbles is merely this: "Have you found the Yellow Sign?"

A weirdly hieroglyphed onyx talisman, picked up in the street by the sharer of his dream, is shortly given the artist; and after stumbling queerly upon the hellish and forbidden book of horrors the two learn, among other hideous things which no sane mortal should know, that this talisman is indeed the nameless Yellow Sign handed down from the accursed cult of Hastur—from primordial Carcosa, whereof the volume treats, and some nightmare memory of which seems to lurk latent and ominous at the back of all men's minds. Soon they hear the rumbling of the black-plumed hearse driven by the flabby and corpse-faced watchman. He enters the night-shrouded house in quest of the Yellow Sign, all bolts and bars rotting at his touch. And when the people rush in, drawn by a scream that no human throat could utter, they find three forms on the floor—two dead and one dying. One of the dead shapes is far gone in decay. It is the churchyard watchman, and the doctor exclaims, "That man must have been dead for months." It is worth observing that the author derives most of the names and allusions connected with his eldritch land of primal memory from the tales of Ambrose Bierce. Other early works of Mr. Chambers displaying the outré and macabre element are The Maker of Moons and In Search of the Unknown. One cannot help regretting that he did not further develop a vein in which he could so easily have become a recognised master.

That's a lot to digest in a single blog entry, but it's worth reading for a number of reasons. First, it's obvious that Lovecraft drew on The King in Yellow in general and on "The Yellow Sign" in particular for concepts and atmosphere for his own weird fiction. Second, it's illuminating to read of the lineage of Chambers' "names and allusions," which can be traced backward to Bierce and forward to Lovecraft and his acolyte, August Derleth. Third, it's very interesting to read Lovecraft's criticisms of the older man Chambers:

Very genuine, though not without the typical mannered extravagance of the eighteen-nineties, is the strain of horror in the early work of Robert W. Chambers . . . [emphasis added].

One cannot help regretting that he did not further develop a vein in which he could so easily have become a recognised master [again, emphasis added].

Those two criticisms, which open and close Lovecraft's discussion of Chambers, can just as easily be leveled at Lovecraft himself. In fact they sometimes have been.

* * * * *

You can read about Robert W. Chambers elsewhere on line or at the library. (The New York Times wrote of him extensively in his time. You might start by reading his obituary, dated December 17, 1933, page 36.) I'll skip the biographical details and write just a little more. First, as Lovecraft wrote, Chambers authored several works of horror, fantasy, and science fiction. (2) Second, he also wrote a book called Police!!! (1915), which may very well have contained the first cryptozoological fiction ever set to print. (3)

Cryptozoology, founded in the nineteenth century but not named until the twentieth, is the science or semi-science of unknown creatures. Its recognized founder was Antoon Cornelis Oudemans (1858-1943), a Dutch zoologist who attempted to describe and classify unknown creatures in his book The Great Sea Serpent (1892). Robert W. Chambers--Oudemans' junior by only seven years--was an enthusiastic entomologist and lepidopterist; his credentials as a science-minded author would appear firm. The point of this is that cryptozoological fiction would not have been likely before science was brought to bear on what would previously have been the stuff of legend or folklore. It's also unlikely that anyone would have written stories on a sensationalistic topic such as cryptozoology before there was a popular press on an industrial scale. I guess I should ask the question then: Can anyone offer another candidate for the first fiction in the young field of cryptozoology?

Notes

(1) Literature? "Stuff!" Chambers might say.

(2) A story called "The Repairer of Reputations" opens Chambers' 1895 collection, The King in Yellow. Set in 1920, the story alludes to recent events, including the administration of a President Winthrop and recent victory in a war with Germany. Winthrop is close enough to Wilson, and of course the United States and Germany were involved in a little tussle ending in 1918. You might say that science fiction blends into prophecy in Chambers' tale. Mostly, though, his projections are simply nonsense.

(3) There is also a hint of forensic entomology in one of the stories.

Robert W. Chambers' Stories in Weird Tales

"The Demoiselle d'Ys" (Aug. 1928)

"The Sign of Venus" (Summer 1973, originally in Harper's Magazine, Dec. 1903)

"The Splendid Apparition" (Winter 1973, originally in In Search of the Unknown, 1904)

|

| A drawing of the King in Yellow, created by Robert W. Chambers himself, that rare combination of accomplished writer and accomplished artist. |

|

| Jack Gaughan, the cover artist for the Ace Books edition of 1965, followed Chambers' model closely. |

|

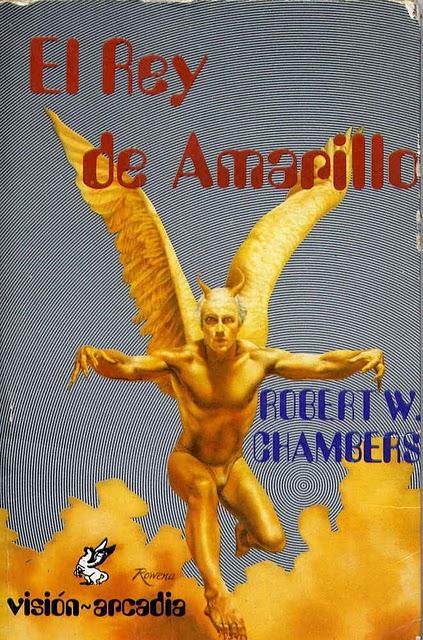

| This Spanish-language version features an Op Art background to Rowena Morrill's illustration. |

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

The futuristic events of "The Repairer of Reputations" are not projections or science fiction. They're examples of the madness of the unreliable narrator.

ReplyDeleteDear Chris,

DeleteThanks for the clarification. I shouldn't have commented on the story without having read it.

TH

I have a piece of art by Robert W Chambers. Its painting of a geisha woman. I am from the area that Mr. Chambers summered and acquired it from his chauffeurs widow. Is anyone interested in viewing this piece?

ReplyDeletelisadi418@verizon.net

Robert is my grand uncle,I would love to see the piece. Do you know if she is still alive, is it possible she has any information about the family. There is very little written, or known. Thank you, hopeful this will reach you even though you posted it three years ago.

DeleteSuzanne Chambers Evans

Hi Suzanne,

DeleteI can't believe I found you here! ... although a post almost years old itself. I have some questions about your grand uncle Mr. Chambers, if you wouldn't mind please email me back at stephen"at"53works.com - thank you so much!