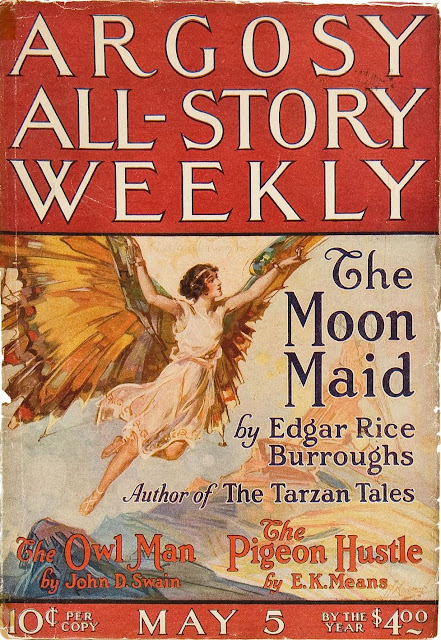

The Moon Maid by Edgar Rice Burroughs was first published as a five-part serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly, from May 5 to June 2, 1923. I have the Ace paperback edition from 1962 with cover art by Roy G. Krenkel. Krenkel's illustration is essentially a reworked version of an earlier illustration by J. Allen St. John, who did so many covers for Weird Tales. That's nothing at all against Roy Krenkel. He was just doing what editor Donald A. Wolheim wanted him to do. (1) We'll hear a little more about J. Allen St. John in the next part of this series.

* * *

As it turned out, The Moon Maid was the first of a trilogy that included a part two, The Moon Men, and a part three, The Red Hawk. All three parts have been published together as an omnibus edition with the all-inclusive title The Moon Maid. To make things more confusing, The Moon Maid is actually a prequel--a kind of back-construction--to The Moon Men, which was written first and in a different form. The Red Hawk is a short sequel to The Moon Men. Ace Books put out a combined printing of parts two and three in 1963. I'll cover that one book and its two parts in the next two installments in this series. Then there will be one more Moon book before I get back to my series on Utopia and Dystopia in Weird Tales. I've been working on that series for ten months now, which is way too long. I might reach a year by the time I'm finished with it.

* * *

I could write a lot more about The Moon Maid than what you'll read here, but I'd better not. I'd better stick to the subject, which is Utopia/Lost Worlds versus Dystopia, eventually as they appeared in Weird Tales. That "Dystopia" needs a second part, though.

The first part of my thesis is that Utopia made its way into Weird Tales by way of the Lost Worlds-type story. I'll let you know now that the second part of my thesis is that the Alien Invasion-type story can be seen as the popular equivalent of Dystopia, just as Lost Worlds is a popular equivalent of Utopia. (There is reason to think that Utopia is actually a kind of Lost Worlds story rather than the other way around. In other words, whether it came first or second, Utopia was subsumed at some point by Lost Worlds, especially after Lost Worlds became a staple of science fiction and fantasy, and especially as the Lost Worlds story was cast into the future or into the past.) As I have already written, Utopia and Dystopia seem to me high, refined literary genres. They are taught in literature classes and are the subject of scholarly research. They may work better in academia than in popular (or subliterary) forms, such as popular magazines, pulp magazines, mass-market paperbacks, comic books, and movies. Maybe it's through Lost Worlds that Utopia found its way into the pulps. Likewise, Alien Invasions might represent Dystopia in those same pulpy pages. Taken together, Lost Worlds and Alien Invasions make up a really large percentage of science fiction and fantasy stories. I'll have more on all of that as I finish off my previous/current series.

* * *

Burroughs cast The Moon Maid into what was then the future. It begins on Mars Day--June 10, 1967. A half-century of war has come to an end and the world is relieved and overjoyed. (2) The story begins on board a transoceanic airship called the Harding. (3) It begins, too, with a framing device, a needless framing device, I might add, except that Burroughs had to figure out how to write The Moon Maid as a setup for The Moon Men, which is the true and original center of his Moon trilogy (and not just because it's part two). His solution was to create a series of characters who live through the centuries as reincarnations of a man named Julian. So we have to let the framing device slide. The Moon Maid is also a club story, recounted by Julian 5th in the Blue Room of the airship Harding on its way from Chicago to Paris.

It's called Mars Day because it's the day that Earth has established contact with Mars, John Carter's Barsoom in fact. That makes the Moon trilogy peripheral to Burroughs' Mars novels. Well, why not? If you've made one success, why not try for another by hanging the second onto the first? Anyway, there is a detailed account in The Moon Maid of how men of Earth make radio contact with an extraterrestrial intelligence. I'm reminded of James E. Gunn's book The Listeners, about which I wrote not very long ago. I wonder if this was one of the first instances of such contact in American science fiction, or science fantasy, which is a better term, I think, for Burroughs' work.

Julian 5th is from the future and so remembers things that haven't happened yet. One of them is the establishment of the International Peace Fleet, "which patrolled and policed the world." Here, then, is an even more striking parallel than with James E. Gunn's book, this time with the film version of Things To Come by H.G. Wells (1936). In both are decades of disastrous war. Then comes an air fleet designed to police the world, to make peace, to keep the peace. In both, power comes from above: the all-seeing eye of the superior and altruistic airman looks down upon the Earth's surface, helping to ensure that no evil is done by men. In one, tyranny is imposed by those airmen, specifically their leader, Cabal (who wants to conquer the Moon by the way). In the other, tyranny comes from without by way of an alien invasion. I will add that sometimes men of Earth are the aliens and the invaders.

* * *

Julian 5th tells of how a crew of Earthmen leave on board a rocketship to Mars. One of the crew, named Orthis, is twisted inside. (Ironically, ortho- denotes something straight.) By his actions, the rocketship, called The Barsoom, is forced to land on the Moon, which proves to be a Lost World. As in so many Lost Worlds stories, there are anthropological or ethnological descriptions of peoples, cultures, languages, customs, and so on. And as in so many--if not every--Burroughs story, there is a maid, here the Moon Maid, who needs rescuing. Maids or damsels are always in distress. They are always getting themselves kidnapped and threatened, often with marriage to unwanted suitors. That's an old story. But I wonder if George Lucas could have gotten his Princess Leia from Burroughs' many maids, damsels, and princesses in need of rescuing. (4) The Moon Maid is also like a Ruritanian romance, which is simply a Lost Worlds story set in modern Europe.

* * *

Orthis reminds me of Weston, the villain in C.S. Lewis' Space Trilogy. In Lewis' first book, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Weston seeks to conquer Mars as a first step towards conquering other planets, "planet after planet, system after system, till our posterity--whatever strange form and yet unguessed mentality they have assumed--dwell in the universe wherever that universe is habitable." (Weston and Cabal also have their similarities.) In Perelandra (1943), Weston hopes to bring about a fall from grace among the newly made people of Venus. If Eden or Paradise is God's Utopia, then Weston's goal in Perelandra can be seen as anti-utopian, in other words, perhaps, dystopian. (Weston is the alien invader on both Mars and Venus.) In That Hideous Strength (1945), the final installment of Lewis' trilogy, the threat is in fact dystopian. But that new Dystopia to be established on Earth doesn't come by way of an alien invasion. Instead it is homemade: it comes from Earth, for the men of Earth are "bent" (vs. straight, or orthic, my new word), thus the status of our world as a cosmically quarantined or "silent" planet in Lewis' trilogy. I'm reminded of a quip from Immanuel Kant: "Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made."

* * *

It's worth noting that Burroughs wrote first and Lewis came after. It's also worth noting that Lewis' gripe was against Wellsian science fiction rather than with fantasy or science fantasy. Lewis once read Burroughs and "disliked it," he wrote. Lewis didn't go out of his way to poke fun at Burroughs, though, maybe because Burroughs was an American pulpwriter rather than a British man of letters. Burroughs was low; Wells was high. More to the point, Wells was an unbeliever, an advocate of science and maybe even Scientism, a socialist, almost certainly a materialist, possibly a believer in what we should all know by now is the specious idea of Progress. (Jack Williamson had a different opinion about Wells and Progress.) In other words, Wells believed in many things that were anathema to C.S. Lewis in his maturity. The two were in natural opposition to each other.

* * *

Like Weston, Orthis travels between worlds seeking to conquer them, corrupt them, ultimately to overthrow them or tear them down. He has his sights set first on the Moon Maid's people, then on Earth itself. In The Moon Maid, Orthis enlists the aid of other Moon Men and he leads them to victory. Those men--the same Moon Men of the second of Burroughs' trilogy--are called Kalkars. They are destroyers of civilization and of "the old order." (p. 89) They were to have been Bolsheviks or communists in Burroughs' original version of The Moon Men. In reworking that story, he turned them into aliens who eventually invade and subdue Earth.

The Moon Maid, Nah-ee-lah says of the Kalkars:

"They will make slaves of us [. . .] and we shall spend the balance of our lives working almost continuously until we drop with fatigue under the cruelest of taskmasters, for the Kalkars hate us of Laythe and will hesitate at nothing that will humiliate or injure us." (p. 109)

I don't know about you, but to me they sound like socialists. I'm sure that was Burroughs' intent.

A fellow prisoner explains to Julian 5th the origins of the Kalkars:

"The Kalkars derive their name from a corruption of a word meaning The Thinkers. [. . .] (5) There is a saying among us that 'no learning is better than a little,' and I can well believe this true when I consider the history of my world, where, as the masses became a little educated, there developed among them a small coterie that commenced to find fault with everyone who had achieved greater learning or greater power than they. Finally, they organized themselves into a secret society called The Thinkers, but known more accurately to the rest of Van-ah [i.e., the Moon] as those who thought that they thought. It is a long story [. . .] but the result was that [. . .] The Thinkers, who did more talking than thinking, filled the people with dissatisfaction, until at last they arose and took over the government and commerce of the entire world. [. . .] The Thinkers would not work, and the result was that both government and commerce fell into rapid decay." (pp. 120-121)

Stupid, poorly educated, ignorant, illiterate. Pseudo-intellectual, full of talk, lazy, destructive, incompetent. Hateful, envious, always seeking to enslave, hurt, and humiliate those who oppose them: Yeah, they're socialists.

In the historical past, the Kalkars tore everything down and destroyed all books and written records. They lack intellectual powers and are ignorant of science and technology. Although they themselves are not numbered, their cities are, for example City No. 337: Burroughs foresaw the dehumanization that is part of the socialist program. (6) Unfortunately, the Kalkars succeed in taking over the Moon, and The Moon Maid ends like The Empire Strikes Back: abruptly, without a clear resolution, and with some dissatisfaction on the part of the reader. Like I said, the first book was meant to set up the second. Readers had to wait a couple of years to find out what happens next.

* * *

I finished reading The Moon Maid on August 30. On that day, the Kalkars took Laythe and the Taliban took Afghanistan.

To be continued . . .

Notes

(1) See the interview with Roy Krenkel in The Edgar Rice Burroughs Library of Illustration, Volume Three (Russ Cochran, 1984), specifically page 112.

(2) In the real world there was also an end to war on June 10, 1967. This one--the Six-Day War--was on the opposite end of duration to the half-century in The Moon Maid. In it, Israel proved victorious and Jerusalem was liberated, we hope forever.

(3) Warren G. Harding was president when The Moon Maid first went to print. He died two months to the day after the last installment appeared.

(4) There are similarities in the names of planets, too: Barsoom and Jasoom. Tatooine and Dantooine. And with C.S. Lewis: Malacandra, Thulcandra, Perelandra.

(5) Kalkar is a homophone for calcar, meaning "spur." Burroughs was a horseman. Maybe his name for his Moon Men was meant to evoke the imagery of men who ride other men or put the spurs to other men.

(6) 337 is a prime number by the way. Significance? Some or none?

Original text copyright 2021, 2023 Terence E. Hanley