In his critique of Charles Fort, John W. Campbell, Jr., wrote that Fort had not done "the hard work of integrating [his data] and finding the pattern." Evidently that's what Campbell was looking for and what he tried to do in his own research: integrate the data and find the pattern.

Fort was a lifelong collector. His life's work consisted of collecting accounts of strange, unexplained, and anomalous phenomena from newspapers, magazines, journals, and other sources in print, then assembling them into four books published from 1919 to 1932. (His last, Lo!, came out two days after his death.) Fort may not have come up to Campbell's standards, but I'm not sure that he failed to integrate his data or to find a pattern, either. He famously concluded: "I think we're property." (The Book of the Damned, 1919, Chapter 12) That seems to me the result of an integration and the discovery of a pattern.

If we summarize the Fortean method, it might be that meaning, significance, or the establishment of patterns comes from the piecing together of data or information that is separated in both time and space. From "The Call of Cthulhu" (1926, 1928):

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. [. . .] The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

and:

But it is not from them [the Theosophists] that there came the single glimpse of forbidden aeons which chills me when I think of it and maddens me when I dream of it. That glimpse, like all dread glimpses of truth, flashed out from an accidental piecing together of separated things--in this case an old newspaper item and the notes of a dead professor.

So it looks like Lovecraft's narrator availed himself of the Fortean method by piecing together "disassociated knowledge" and "separated things." And in examining these data, the narrator arrives at a correlation of contents, in Campbell's terms, perhaps, at integration and a discovery of patterns.

The novel Sinister Barrier was the headliner in the first issue of Campbell's fantasy magazine Unknown. The author was Eric Frank Russell, a confirmed Fortean. In his introduction, Russell in fact acknowledged Fort as a posthumous co-author of his story. He also acknowledged the Fortean Society of America and mentioned Lovecraft, Ambrose Bierce, and other "imaginative and enquiring minds" who had "been 'removed' with expedition, and with subtle cunning." (Oh, those disappearing Ambroses!) Then comes a second introduction, a description of and speculation on a seemingly insignificant journalistic account: eight dead starlings falling from the sky in New York City, and a ninth so frightened that it flies into a restaurant window. What killed the eight and frightened the ninth? Only the integration of data, the correlation of contents allows for an answer . . .

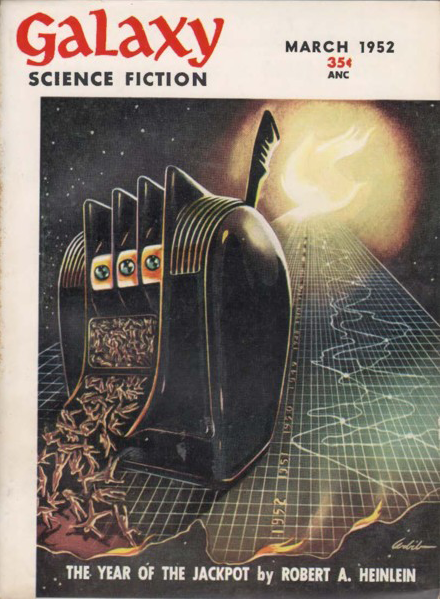

Campbell wrote his critique of Fort in the form of a letter to Russell, dated October 1, 1952. In it, Campbell called for a piecing together, an integration of separate things. And from that integration, he wanted the making of patterns. Earlier that year, in March 1952, Robert A. Heinlein's story "The Year of the Jackpot" had appeared in Galaxy Science Fiction. Heinlein's hero is statistician Potiphar Breen. Like Charles Fort, Breen collects data from newspaper accounts of seemingly unrelated phenomena. In other words, Breen employs the Fortean method, but he takes it one step further: he answers Campbell's call for integration and pattern-making. It is through Breen's integration and analysis that a pattern emerges, a pattern of cycles that just happen to come together in a single year, the year of the jackpot. And what a terrible jackpot it is! There is also a parallel construction to Fort's I think we're property: Breen tells his girlfriend Meade, "I think we're lemmings."

So did Heinlein answer Campbell's call directly, meaning, did Heinlein get the idea for his story from Campbell in regards to what Campbell thought of as Fort's shortcomings? I doubt it. For one, "The Year of the Jackpot" was in H.L. Gold's Galaxy versus Campbell's Astounding Science Fiction. More importantly, I doubt that Heinlein would have needed any hints or nudges or ideas from anyone else at that point in his career. He was his own man and his own writer. He had plenty of imagination and almost certainly didn't need anything from anyone else.

I didn't go looking for "The Year of the Jackpot." In an almost occult coincidence, I just happened to read it the other night. (I write on April 27, 2022.) I had read the story before, I think. This time I found it in Nightmare Age, a collection of unpleasant or even terrible futures, edited by Frederik Pohl and published by Ballantine Books in 1970. Not to take anything away from anyone else represented in this book--there are some very good writers and very good stories in Nightmare Age--but Heinlein was simply a step ahead of the others, in his style, in his way of putting together a story, in his dialogue and characterization, finally in his way of conveying real feeling and what it is to live as a human being. A story that begins lightly turns serious and heavy by the end. And those are the final words of "The Year of the Jackpot": THE END.

Anyway, the Fortean method made its way into both fiction and nonfiction, as early as "The Call of Cthulhu"; certainly by the time of Sinister Barrier, in which it was placed in full view of the reader; in "The Year of the Jackpot," in which it was no longer necessary to mention any Fortean background to a story; more obviously in all of the nonfictional or pseudo-nonfictional accounts of Fate and other Fortean studies published after midcentury. Behind the Flying Saucers by Frank Scully (1950) and The UFO Annual by Morris K. Jessup (1956) are good examples. We should remember that the short story that uses or refers to newspaper accounts has precedence in the work of the Amazing Disappearing Ambrose Bierce (1842-?). So maybe Fort followed Bierce.

None of this is to say that Lovecraft or Heinlein wrote their stories with an awareness of Fort and the Fortean method in mind. We don't know that they did. In fact, Lovecraft seems to have worked in the Modernist method of assembling his stories from the things he found around him, like John Dos Passos or T.S. Eliot. (I guess Fort did the same thing. So was Fort a Modernist?) The case of "The Year of the Jackpot" seems more equivocal. That single parallel construction--"I think we're lemmings"--seems to give the game away, though. Maybe Potiphar Breen is a cross between Charles Fort and John W. Campbell, Jr.

Original text copyright 2022 Terence E. Hanley

Campbell's standards for research don't seem to have been particularly high. He did after all promote several crackpot theories.

ReplyDeleteHi, TMN,

DeleteI agree. If his research had really been of merit, we would today have results. Instead, as far as I know, there aren't any.

Thanks for writing.

TH