Musician, Teacher, Author, Poet

Born March 5, 1922, Oakland, California

Died May 27, 1970, Guadalajara, Mexico

Willard Noah Marsh was born on March 5, 1922, in Oakland, California. His parents were Louis and Goldie D. (Greene or Green) Marsh. Louis Marsh, a native of France, died on May 13, 1928, in San Mateo, California. I don't know what happened to Goldie, but in 1930, Willard and his brother, Matthew E. Marsh, were enumerated in the Federal census with their aunt and uncle, Henry and Lenora M. Green, in Berkeley, California.

Willard N. Marsh graduated from Garfield Junior High School and Berkeley High School. A description of his papers at the University of Iowa Libraries notes Marsh's talents as a musician:

While in Oakland High School he displayed a virtuosity with trumpet and trombone which led to an era as musician-impresario--the launching of "Will Marsh and the Four Collegians" in an Oakland roadhouse--which subsequently financed his education at the State College at Chico.

Marsh was two years into his program at Chico State University when his country came calling. On September 18, 1942, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. He received his technical training at Scott Field in Illinois and served in the U.S. Army Air Forces in the South Pacific in the field of radio communications. The Oakland Tribune printed his letter, entitled "Life on an Atoll," on May 5, 1944 (p. 28).

On September 10, 1948, Marsh married George [sic] Rae Williams in California. She was a former actress with the Pasadena Playhouse. By then, Marsh's writing career had already begun to take off. His first work listed in The FictionMags Index is in fact his poem "Bewitched," which appeared in Weird Tales in March 1945. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Marsh wrote prize-winning stories and poems. In 1950, he was living with his wife in Contra Costa County, California, and calling himself a novelist.

Marsh studied at Chico State University, San Francisco State College, and State University of Iowa. From 1950 to 1958, he gave private instruction in creative writing in the United States and Mexico. He received his bachelor's degree from the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop in 1959 and his master's degree in 1960. In September 1959, he began as an assistant professor of English at Winthrop College in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Marsh spent two years at Winthrop, three at the University of California, Los Angeles (1961-1964), and two more at North Texas State University, Denton (1968-1970). He retired to Mexico very near the end of his life and died of a heart stoppage on May 27, 1970, in Guadalajara, Mexico. He was buried at Municipal Cemetery, Ajijic, Mexico, a fitting place for him to come to rest, for Ajijic has been a place for writers and artists for more than one hundred years.

* * *

From 1945 to 1969, Willard Marsh wrote dozens of stories and poems published in pulp magazines, men's magazines, slick magazines, and literary journals. The FictionMags Index and the Internet Speculative Fiction Database list the following stories in fantasy and science fiction magazines:

- "Bewitched" in Weird Tales (poem, Mar. 1945)

- "Moon Bride" in Different (vignette, Sept./Oct. 1946)

- "Astronomy Lesson" in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (short story, June 1955)

- "The Ethicators" in If (short story, Aug. 1955)

- "Machina Ex Machina" in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (vignette, May 1956); reprinted in Fiction #39 (1957)

- "Poet in Residence" in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (short story, Sept. 1958); reprinted in Venture Science Fiction (June 1964)

- "Forwarding Service" in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (short story, June 1964); reprinted in Wanderer durch Zeit und Raum (Oct. 1964)

- "Everyone's Hometown Is Guernica" (or "Cuernica") in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (short story, Aug. 1965)

- "Stay Out of Our Time!" in Worlds of Tomorrow (novelette, June 1964)

- "Inconceivably Yours" in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (short story, Sept. 1964)

- "The Sin of Edna Schuster" in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (short story, Feb. 1965)

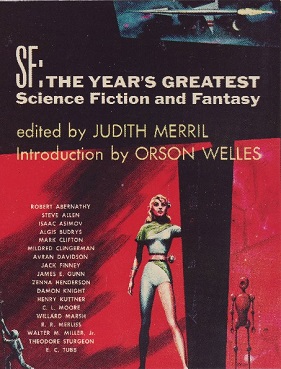

His story "The Ethicators" was in SF: The Year's Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Judith Merril and published in 1956.

Marsh also wrote for:

Mystery, crime, and detective magazines: Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, Mercury Mystery Magazine.

Men's magazines: Adam's Bedside Reader, Cavalier, The Dude, Gentleman, Rogue, Sir Knight, Spree.

Slick magazines: Esquire, Playboy, The Saturday Evening Post.

Literary journals: Antioch Review, Approach, Georgia Review, Prairie Schooner, Southwest Review, Transatlantic Review, University of Kansas City Review, Yale Review, and others.

And his stories were in: Best American Short Stories: 1953, Best Saturday Evening Post Stories: 1954, and Prize Stories, 1957: The O. Henry Awards.

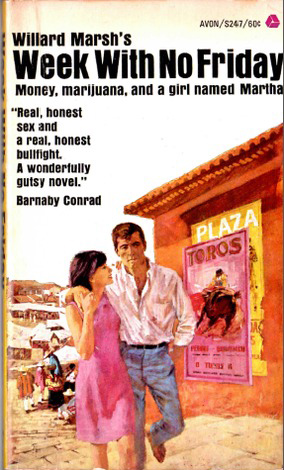

He had at least two published books to his credit: a novel, Week With No Friday (Harper & Row, 1965; Avon Books, 1967), and a collection of stories, Beached in Bohemia (Louisiana State University Press, 1969). He also wrote drafts for an unpublished novel, Anchor in the Air.

Willard Marsh was born during the interwar period and was one from those generations that accomplished so much and helped to make America such a prosperous, creative, fun, and interesting place in which to live. His career perhaps encompassed what we might consider a golden age for writers and artists in our country, a time when there were workshops, university programs, correspondence courses, night schools, and so on in which to learn the crafts of writing, drawing, and painting; also contests and competitions, fairs, shows, and exhibits; writer's and artist's groups, colonies, conferences, and conventions; and perhaps most importantly, magazines, fanzines, journals, and newspapers, big, small, and very small, printed on pulp and slick paper and everything in between, publications to receive the work of so many talented, energetic, and ambitious people. What a grand time it must have been, though grand perhaps only in retrospect, as grand times usually are.

* * * Happy New Year! * * *

- "Changing Trend in Reading Said Encouraging to Writers" [by Ann Blackmon] in The State (Columbia, SC), October 20, 1959, section B, page 15.

- Description of Willard N. Marsh's papers, University of Iowa Libraries, here.

|

| SF: The Year's Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy (1956), edited by Judith Merril and with Willard Marsh's name on the cover. His story "The Ethicators" was inside. Cover art by Ed Emshwiller. |

|

| Willard Marsh's Week with No Friday was originally in hardback, but paperback covers are usually more interesting. That proved to be the case here in Avon's edition of 1967. Artist unknown. |

|

| Willard Marsh seems to have had high literary ambitions, but he wasn't above writing for men's magazines. Here is his name on the cover of Gent for August 1958. Those were the days. |

|

| Willard N. Marsh (1922-1970) |