I wanted to be done with this topic, but there is always more of everything, at the door and waiting to come in.

Today (Sept. 10, 2024), I read an article about Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957), that notorious, mid-century, whacked-out, Freudian-Marxist, crackpot pseudoscientist and chaser after flying saucers. (1) I'll tell you, there aren't enough adjectives and epithets to describe this guy. Anyway, I came across a quote from him that leads to another quote that leads back to the topic of Strength Through Joy from the other day. I say "the other day" in the Midwestern sense, meaning any day between yesterday and several weeks ago.

Here is Reich on joy and strength:

This future order cannot and will not be other than, as Lenin put it, a full love-life yielding joy and strength. Little as we can say about the details of such a life, it is nevertheless certain that in the Communist society the sexual needs of human beings will once more come into their own. . . . Evidence that socialism alone can bring about sexual liberation is on our side. (2) [Boldface added; ellipses in Mr. Panero's original article. See the note below for the source.]

Ah, so Strength Through Joy came from Lenin. But where from Lenin? Well, here from Lenin:

"Besides, emancipation of love is neither a novel nor a communistic idea. You will recall that it was advanced in fine literature around the middle of the past century as 'emancipation of the heart'. In bourgeois practice it materialized into emancipation of the flesh. It was preached with greater talent than now, though I cannot judge how it was practiced. Not that I want my criticism to breed asceticism. That is farthest from my thoughts. Communism should not bring asceticism, but joy and strength, stemming, among other things, from a consummate love life. Whereas today, in my opinion, the obtaining plethora of sex life yields neither joy nor strength. On the contrary, it impairs them. This is bad, very bad, indeed, in the epoch of revolution.

"Young people are particularly in need of joy and strength. Healthy sports, such as gymnastics, swimming, hiking, physical exercises of every description and a wide range of intellectual interests is what they need, as well as learning, study and research, and as far as possible collectively. This will be far more useful to young people than endless lectures and discussions on sex problems and the so-called living by one's nature. Mens sana in corpore sana. Be neither monk nor Don Juan, but not anything in between either, like a German Philistine." [Boldface added.]

That long quote is from "Lenin on the Women's Question," an interview conducted in 1920 by Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), a German Marxist and feminist. You can easily find it on the Internet.

Lenin was of course a socialist, but he was of the international variety. Nazis were socialists, too, but of the opposing national variety. These people couldn't stand each other. And yet the Nazis seem to have gone to Lenin for his concept of strength through joy, at least when it came to "[h]ealthy sports, such as gymnastics, swimming, hiking, physical exercises of every description." Activities like these were of course part the program under the Nazi organization Kraft durch Freude, or KdF, established in 1933, thirteen years after Lenin gave his interview.

It seems to have been Reich and men like him, particularly of the Frankfurt School, who departed from Lenin's proscription against what he considered the bourgeois "emancipation of the flesh" and a "plethora of sex life." (3) In Lenin's analysis, these things impair rather than yield joy and strength. On top of that, they're "bad, very bad" for the Marxist revolution. Imagine: Lenin seems to have come out in favor of conventional and committed love-relationships between men and women, all the better, I guess, to keep the revolution going. The revolution, after all, was the thing.

Reich, a Marxist to be sure but a Freudian as well, went the other way. He and his followers, even unto today, would seem to be the Philistines in Lenin's formulation, although I'm not sure I understand the reference exactly. (Maybe it was to Rousseau, a Swiss, or to Goethe, a German, but I just can't say. See the note below.) In any case, it looks like Lenin has been kicked into the dustbin of history. After all, it is critical theory and other ideas of the Frankfurt School and the New Left--all pretty heavy on sex and what people call gender--that have taken over the minds of people in academia and the Western élite. In contrast, who today calls himself a Marxist-Leninist? Poor Lenin. He must be turning over on his bier.

* * *

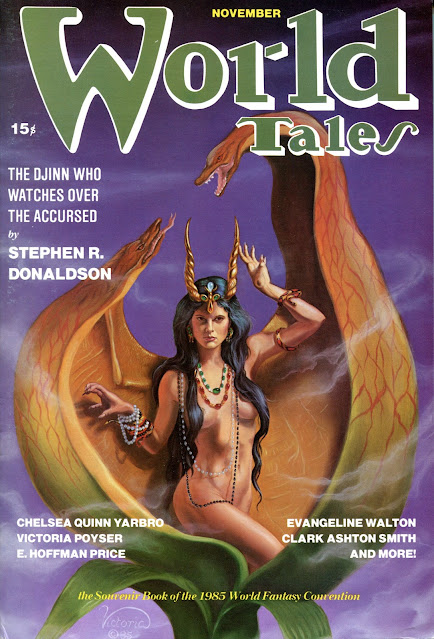

By the way, Reich's followers included Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer, a sure indication that even very intelligent people can be extremely stupid. As for the literature and cinema of science fiction and fantasy, Reichian ideas--rather, his gadgets--are in Barbarella (1968) and Sleeper (1973), as well as in the video of Kate Bush's song "Cloudbusting" (1985). One of those gadgets, the orgone accumulator, makes me think of L. Ron Hubbard's E-meter, a different kind of gadget that he swiped from Volney G. Mathison (1897-1965). Both are pseudoscientific instruments that would have found an easy place in the science fiction of their day. They may very well have been inspired by science fiction, just as flying saucers were. (Like Hubbard, Reich believed that aliens from outer space have come to Earth.) So the path seems to start in science fiction before moving into the real world, after which it goes back into science fiction. The problem is that people forget where it all started. They lose the origin story and see the beginnings of these things in the real world rather than in the imagined worlds of science fiction.

By the way, both Wilhelm Reich and L. Ron Hubbard were influenced by Freudian psychology, which you could also call a pseudoscience if you want.

Connections between real-world pseudosciences and the imaginary worlds of science fiction continue. For example: Reich's Maine estate, called Orgonon, recalls the Valley of the Pines, run by Joseph A. Sadony (1877-1960) close to the shores of Lake Michigan. In attendance there for many years was Meredith Beyers (1899-1996), who, like Volney Mathison, was a teller of weird tales.

Another example: science fiction author L. Ron Hubbard had his own real-world hideout. Sometimes it was on board a ship at sea. Towards the end of his life, Hubbard, depraved as always but then in extreme decay, retreated to a secluded ranch in California. Instead of being like Captain Nemo on his Mysterious Island, Hubbard put his ocean-going days behind him and died in his bed, in a motor home, his hair and nails grown long the way people used to say happened with corpses. Lenin died in bed, too. His corpse has remained static in the one hundred years since his death. Happy death anniversary, V.I. We don't miss you.

* * *

These men and men like them were and are like Bond villains or pulp-fiction or comic-book supervillains who live in great wealth in their secret lairs, secluded estates, hidden valleys, expensive vessels, and other hideouts peopled with anonymous but extremely loyal henchmen who, as it happens, always die in droves when the hero shows up. Unlike fictional villains, however, the real-world pseudoscientist, theorist, and experimenter usually lives with only few attendants, their numbers often dwindling as the years go by, and he often dies alone, in poverty and misery and maybe even suffering from insanity. This is what happens, I guess, when you separate yourself from nature, fact, truth, and reality, also from yourself and other people.

Marxists and Nazis of course have their own pseudosciences and their pseudoscientific processes and gadgets. Marxism is itself, in its whole, a pseudoscience, i.e., the pseudoscience of what Marxists calls History. And what else are the Marxist Workers' Paradise and the Nazi Thousand-Year Reich (a different Reich from Wilhelm) than just larger versions of those insular and closed-off places where Reich, Sadony, Hubbard, and men like them played with their pet theories and carried out their abstruse researches and pointless experiments? In contrast, Captain Nemo was only a fictional character. He was harmless. In contrast, too, Edgar Rice Burroughs was only a real-world author. All of his theorizing and experimentation happened only on paper. He was harmless, too. But maybe we can say that his Tarzana was the secular equivalent of those hidden and isolated places of pseudoscience and separation, a kind of Disneyland not open to the general public.

Marxism and the "science" of History, Nazism and the "science" of race, orgone energy, cloudbusting, Dianetics, Scientology, flying saucers, contact with aliens--including sexual contact with aliens--ancient aliens, alien abductions, alien invasions and infiltrations--on and on these ideas go. Some are mostly harmless. All are, at least in part, pseudoscientific. Among them are ideas, Marxism and Nazism being the chief examples, that are dangerous in the extreme, to the point of being lethal to countless millions of human beings. What does it say about us that we keep coming up with these things? That they keep coming back even though we chase them away over and over again? What does it say about us that we keep falling for them? Believing in them as keys to our understanding, of ourselves, our history, and the world in which we live? Believing them to be keys to making our lives better and happier? What do all of these things say about us?

Notes

(1) The article is "Marx of the Libido" by James Panero on the website of City Journal, Summer 2024, accessed by clicking here.

(2) From his essay "Politicizing the Sexual Problem of Youth" in Sex-Pol: Essays, 1929–1934 (1972).

(3) I'm interested in the origins of the supposed bourgeois idea of the "emancipation of the heart." I found this phrase in an online abstract of a paper about the German authoress Marie Louise von François (1817-1893). I also found it in reference to both Rousseau and Goethe. I can't say whether I'm on the right track, though. Maybe if we could find a handsome prince to kiss the sleeping Lenin in his glass coffin, he would wake up and tell us what he meant.

Speaking of the Swiss and glass coffins, an American woman killed herself in Switzerland using a suicide coffin. This happened on September 23, 2024. See what I mean when I say that there are always more things waiting to come in the door? Anyway, last night (Sept. 24, 2024) I read "Welcome to the Monkey House" by Kurt Vonnegut (1968). The story involves suicide parlors where people voluntarily go to their deaths. How prescient. There are also suicide chambers (pun possibly intended, given the author's surname) in "The Repairer of Reputations" by Robert W. Chambers (1895) and in the film Soylent Green (1973), based on the 1966 novel by Harry Harrison. These ways of killing ourselves originated in science fiction. Now they have come into the real world. Is it possible for them to go back into science fiction again? Or is it too late for that?

|

| Wilhelm Reich and son Peter, by the artist MacNeill, from High Times #9, May 1976. Note the flying saucers and the Vernian rocketship. Note also the two orbs as in Robert W. Chambers' illustration for his own King in Yellow (1895). |

Original text copyright 2024 Terence E. Hanley