I began writing this blog five years ago. Today is the anniversary. I started out and have been writing more or less randomly. Not long ago, though, I looked through the remaining authors and gave them some kind of organization. Although there are still several hundred to go, I can see an end to all this, although that end might be several years out.

One of the writers I missed in my previous groupings of tellers of weird tales from the past is William Ernest Henley.* I would like to write about him today, but he really belongs with the other writers of the Victorian Age in an entry from October 27, 2011, not only because he was one of them but also because he was a friend of Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), who based his character Long John Silver on Henley.

William Ernest Henley was born on August 23, 1849, in Gloucester, England, and attended The Crypt School in that city. He passed his examination in 1867 and went to work in the field of journalism. Henley edited London (1877-1878), the Magazine of Art (1882-1886), the Scots Observer/National Observer (1888-1893), and a publication called Ana Siken. Through all that, he wrote poetry and through all that he endured ill health, surgical operations, and long stays in the hospital from which he emerged minus a leg.

Henley's time was one of great prosperity and expanding horizons but also one of decadence and looking backward. Henley himself was conservative, but his poetry is forward-looking, not only in its optimism (or at least its undefeated attitude) but also in its anticipation of the verse of the coming century. According to Andrzej Diniejko, Henley and his circle (called the "Henley Regatta") "promoted realism and opposed Decadence," a viewpoint and movement then in fashion. (Quoted in Wikipedia in an entry that is disjointed at best.) If anyone might have cause to feel defeated, pessimistic, or depressed--in other words a candidate for the Decadent vogue of the fin de siècle--Henley was it. From the age of twelve, he suffered from tuberculosis in his bones. Sometime in 1868-1869, he had his left leg taken off below the knee. Henley spent a good deal of time in the hospital, including the years 1873-1875, when his right foot was also diseased. More tragically, Henley's daughter Margaret, who had inspired James Barrie in his creation of Peter Pan, died in 1894 at age five. If his poetry is any indication, Henley remained undefeated by death and disease, however. Here is his most famous work, Invictus, from 1875:

Invictus

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gait,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Here is another poem, presumably on the death of his daughter, and on his own impending end:

In Memoriam: Margaritae Sorori

A late lark twitters from the quiet skies:

And from the west,

Where the sun, his day's work ended,

Lingers as in content,

There falls on the old, gray city

An influence luminous and serene,

A shining peace.

The smoke ascends

In a rosy-and-golden haze. The spires

Shine and are changed. In the valley

Shadows rise. The lark sings on. The sun,

Closing his benediction,

Sinks, and the darkening air

Thrills with a sense of the triumphing night--

Night with her train of stars

And her great gift of sleep.

So be my passing!

My task accomplish'd and the long day done,

My wages taken, and in my heart

Some late lark singing,

Let me be gather'd to the quiet west,

The sundown splendid and serene,

Death.

I am reminded of Ralph Vaughan Williams' musical piece The Lark Ascending, from George Meredith's poem of the same name, published in 1881. To me, The Lark Ascending is both joyful and sad, music about life itself. It also represents, I think, England, about which Henley also famously wrote:

England, My England

What have I done for you,

England, my England?

What is there I would not do,

England, my own?

With your glorious eyes austere,

As the Lord were walking near,

Whispering terrible things and dear

As the Song on your bugles blown,

England--

Round the world on your bugles blown!

Where shall the watchful sun,

England, my England,

Match the master-work you’ve done,

England, my own?

When shall he rejoice agen

Such a breed of mighty men

As come forward, one to ten,

To the Song on your bugles blown,

England--

Down the years on your bugles blown?

Ever the faith endures,

England, my England:--

'Take and break us: we are yours,

England, my own!

Life is good, and joy runs high

Between English earth and sky:

Death is death; but we shall die

To the Song of your bugles blown,

England--

To the stars on your bugles blown!'

They call you proud and hard,

England, my England:

You with worlds to watch and ward,

England, my own!

You whose mail’d hand keeps the keys

Of such teeming destinies,

You could know nor dread nor ease

Were the Song on your bugles blown,

England--

Round the Pit on your bugles blown!

Mother of Ships whose might,

England, my England,

Is the fierce old Sea's delight,

England, my own,

Chosen daughter of the Lord,

Spouse-in-Chief of the ancient Sword,

There's the menace of the Word

In the Song on your bugles blown,

England--

Out of heaven on your bugles blown!

In our time, a poem like that would be called nationalistic, jingoistic, imperialistic, and even fascistic, the pejoratives that the politically correct so readily spew like verbal vomit. I take it as the work of a man who loved his country and all that it had accomplished, including, in an irony that is lost on them, the very freedom of thought and speech that allows the politically correct to criticize the country admired and the sentiments expressed in the poet's work.

William Ernest Henley died on July 11, 1903, in Woking, England. A little more than a quarter-century later, Weird Tales reprinted a poem by him that it called "A King in Babylon." Its author called it "To W.A.":

To W.A.

Or ever the knightly years were gone

With the old world to the grave,

I was a King in Babylon

And you were a Christian Slave.

I saw, I took, I cast you by,

I bent and broke your pride.

You loved me well, or I heard them lie,

But your longing was denied.

Surely I knew that by and by

You cursed your gods and died.

And a myriad suns have set and shone

Since then upon the grave

Decreed by the King of Babylon,

To her that had been his Slave.

The pride I trampled is now my scathe,

For it tramples me again.

The old resentment lasts like death,

For you love, yet you refrain.

I break my heart on your hard unfaith,

And I break my heart in vain.

Yet not for an hour do I wish undone

The deed beyond the grave,

When I was a King in Babylon

And you were a Virgin Slave.

|

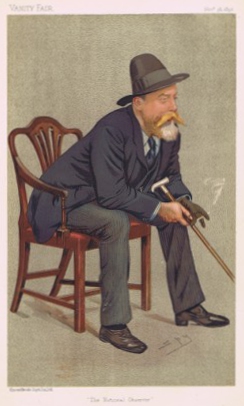

| William Ernest Henley (1849-1903) |

*Revision (Apr. 23, 2016): As it turns out, I did write about him before, but only briefly, in "More Weird Tales from the Victorian Age," October 30, 2011, here.

Original text copyright 2016, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

Original text copyright 2016, 2023 Terence E. Hanley

No comments:

Post a Comment